Boyle Heights: Problems, pride and promise

Fresh from his sauna, a young Chicano combed his hair before an ornate mirror hanging beside the cashier’s cage at a Russian bathhouse in Boyle Heights.

He studied his bronze visage in the gilded, baroque glass, smiled, thanked the Japanese manager and strolled out of the brick building at 1st and Chicago streets.

For 80 years the old mirror at the 1st Street Bath House has reflected the faces of immigrants from around the world who have settled in Boyle Heights. First came the Russians, Jews and Japanese, then the Armenians, Italians and Chinese.

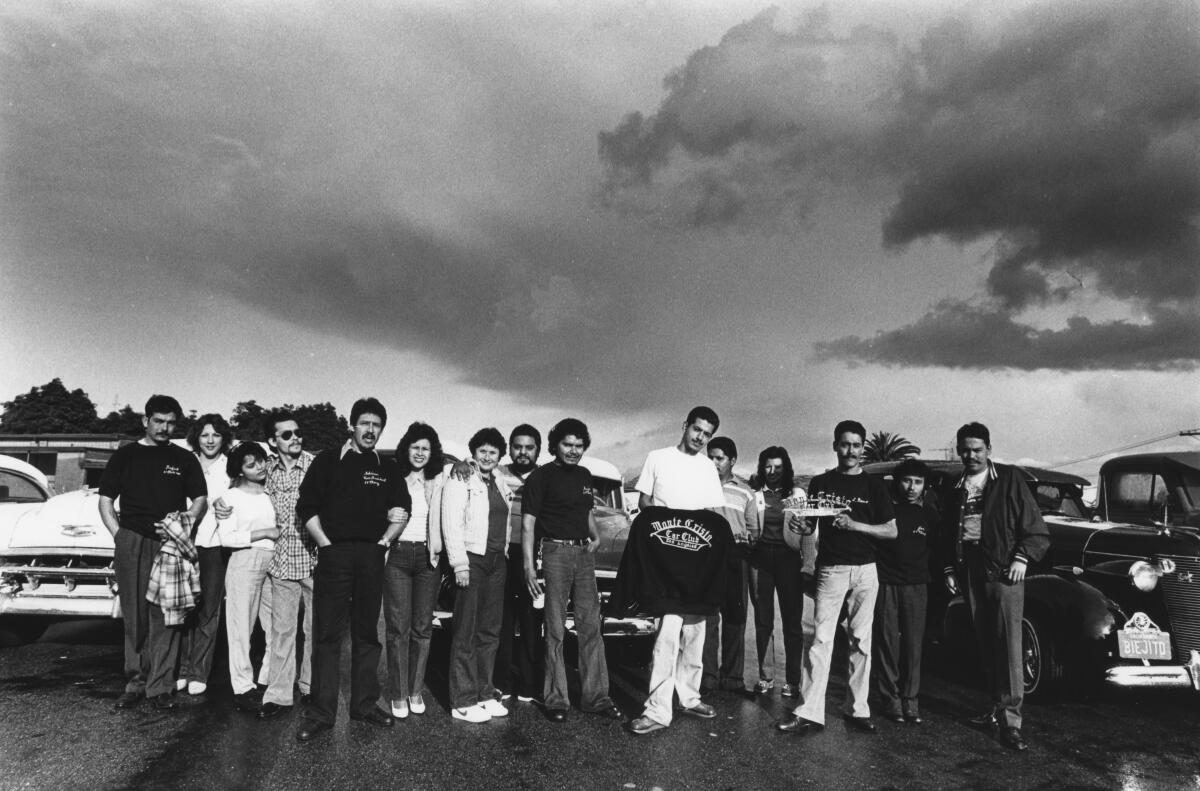

Now Boyle Heights is a barrio, a bastion of Latino culture, populated by Mexicans and Mexican-Americans who began arriving in large numbers 30 years ago. So many have come that Boyle Heights and the East Los Angeles communities adjacent to it have become the Mexican-American capital of the nation.

Boyle Heights lies just five minutes east of the Civic Center, but few non-Latinos venture there. Many view it as a dangerous no man’s land, although police statistics show that Boyle Heights and surrounding communities are among the safest in the city.

In many ways, however, Boyle Heights is a community in distress. Thirty-five years of intense freeway construction eliminated 2,900 homes, displaced 10,000 people and left noise and air pollution in its wake. Schools are crowded. Housing is scarce, and most of the housing that does exist is owned by absentee landlords. Unemployment is higher than in most other areas of the city. There is a sense that the community has little or no political power and is largely ignored by city government.

Still, some see a new determination among Boyle Heights’ 88,000 mostly low-income inhabitants to preserve the area’s ethnic vitality and to improve living conditions.

“There is a new trend here,” said Art Chayra, a Stanford graduate and former Air Force fighter pilot who now owns six stores in a Boyle Heights shopping center. “People are taking pride in East Los Angeles. We’re getting over our inferiority complex.”

For one thing, low-interest loans to refurbish old houses are encouraging many to remain in Boyle Heights rather than move to upscale communities elsewhere in the city when their fortunes improve.

Since 1980, 292 homes in two target areas have been renovated with loans totaling $1 million from the Boyle Heights Community Redevelopment Agency.

Retail business activity has been stimulated by the three-story El Mercado shopping center on 1st Street, a collection of 35 separately owned and fiercely competitive stores that did $10 million worth of business last year. Other signs of renewal are a new First Interstate Bank branch and a Social Security building at Brooklyn Avenue and Soto Street, the commercial heart of the community.

And residents are organizing to make government and corporate institutions more responsive to their needs.

The most dramatic example of this is the rise of UNO, the United Neighborhoods Organization. Born in Boyle Heights, this 5-year-old creation of Roman Catholic priests and Eastside community activists claims a membership of 93,000 families and focuses its energies on issues rather than conventional politics. It has waged aggressive and frequently successful campaigns against everything from high auto insurance rates on the Eastside to the reluctance of banks to grant home improvement loans in the area.

Julian Nava, an educator and former U.S. ambassador to Mexico, who grew up in Boyle Heights, said, “I can’t help but wonder how long it will take before the powers that be realize the important interdependence between the barrio and surrounding communities and work to solve existing problems...”

At the turn of the century, Boyle Heights was an enclave for the wealthy. By the 1930s, it had become the bustling heart of Los Angeles’ Jewish immigrant community of 10,000 households. One-time residents include corporate executive Max Factor and gangster Mickey Cohen.

“I went to school with Mickey Cohen,” recalled one longtime resident who asked not to be identified. “He was a fine, fine boy. He used to steal cookies for me.”

From the Mexican-American population that existed about the same time came such Latino notables as Rep. Edward R. Roybal (D-Los Angeles), actor Anthony Quinn and Nava.

“Each of us grew up with other minorities,” Nava recalled, “and were, therefore, inoculated against prejudice.”

Few descendants of the original Jewish, Molokon Russian and Japanese families remain in what has become a thoroughly Latino community. But reminders of that period are scattered throughout Boyle Heights: venerable tenement buildings, synagogues, wood-paneled Buddhist temples, corner markets and Victorian homes.

The transformation to a substantially Mexican-American community began during World War II when the Japanese population of Boyle Heights was forcibly evacuated by military order, stripped of property and sent to wartime relocation camps.

Then, after the war, European immigrants left Boyle Heights for the new suburbs of Los Angeles. In their wake came Latinos eager to rent homes and establish businesses so close to the center of the city.

More than 30 years later, many billboards, storefront signs and advertisements in the community are in Spanish. Jewish delicatessens and bakeries have been replaced by carnicerias and panaderias, where the aroma of Mexican bread hangs in the air. Bustling sidewalks are lined with restaurants, small neighborhood markets and stores of modest size-many of them sprayed with graffiti-offering such necessities as shoes, clothes, appliances and furniture. Theaters announce Spanish-language movies on their marquees.

El Mercado center, at 1st and Indiana streets, is a hub of Latino commerce and culture where, more often than not, business transactions are conducted in Spanish. To the sound of mariachi music performed live or piped through speakers, shoppers browse through 84,000 square feet of counters and shelves brimming with inexpensive clothing, leather goods, appliances, fruits and vegetables, meats and fish, spices and prepared foods.

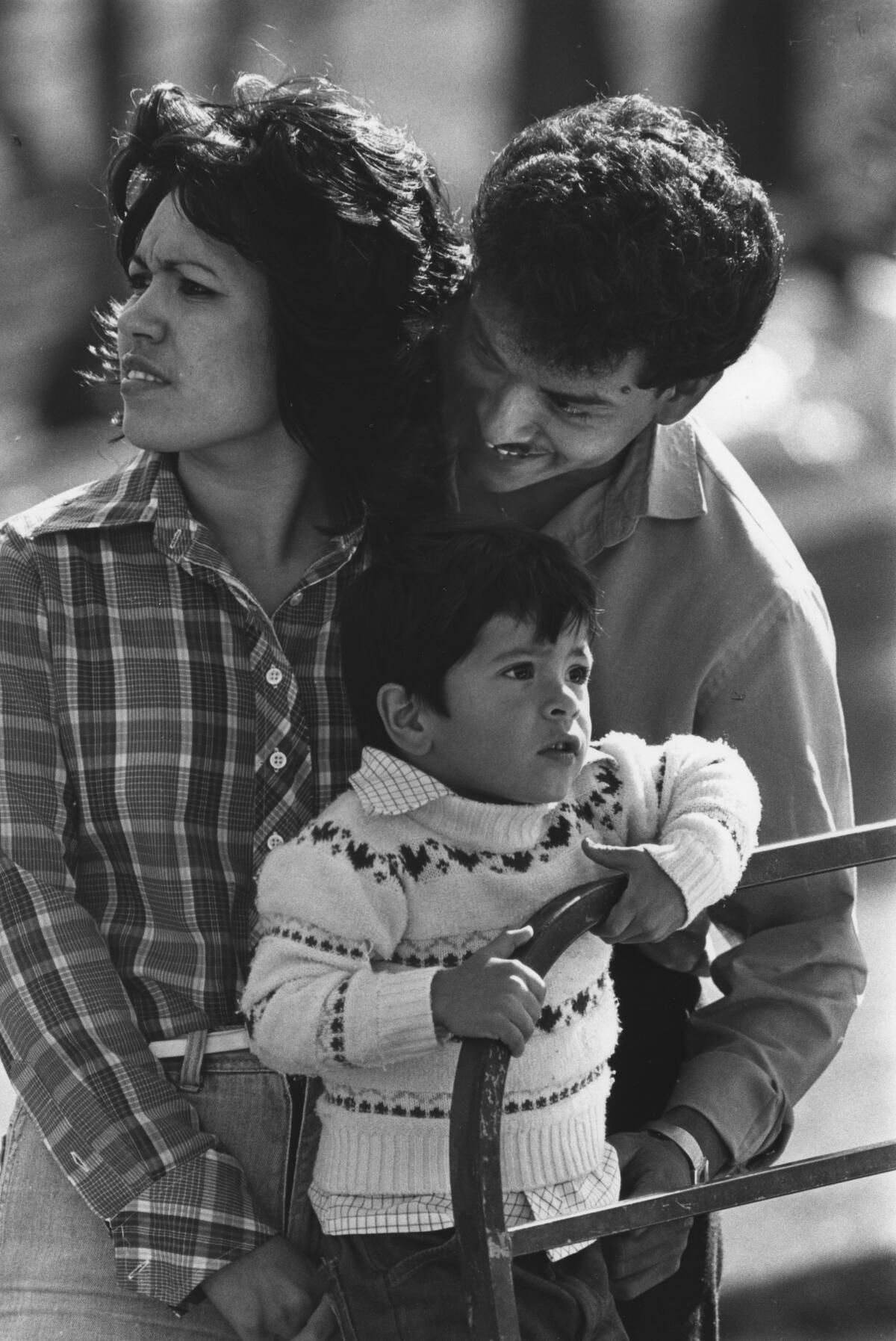

The people of Boyle Heights live mostly in old neighborhoods of wood-frame and stucco houses, many with well-kept gardens of roses, lemon trees, ferns and cactus.

From the time the afternoon school bell rings until just after dusk, front yards, sidewalks and streets come alive with children of the close-knit working-class families. About 50% of the population is under 25, the 1980 Census showed, compared to 39% citywide.

Many houses are visibly dilapidated. Contributing to the physical decay are overcrowding and a substantial transient population of new arrivals who use Boyle Heights as temporary living quarters. Neglect on the part of absentee landlords and low-income tenants who often cannot afford repairs exacerbate the problems.

Boyle Heights has one of the county’s lowest median household incomes—$11,352, compared to $17 ,826 countywide. The median home value in 1980 of $49,700 compared to $88,000 for the county.

About 73% of the residents rent homes or apartments. Median rent is around $150, and the typical unit is a one-bedroom apartment.

“You can fill a vacancy here in two minutes,” said the manager of 12 units on Pleasant Avenue. “Sometimes they (prospective tenants) don’t even ask me to show the place to them. They take it unseen.”

The craftsmen, machine operators and laborers who account for the majority of the Boyle Heights work force commute to jobs at industrial centers and factories on the northern, southern and western edge of the community and to downtown businesses.

Many of the residents work “under intolerable conditions,” said Dr. Pauline Furth, who was raised in Boyle Heights and has practiced medicine in the area for more than 25 years. “Since I once worked in the sweatshops and canneries, I know they are not just complaining when they say, ‘My arms and back hurt.’ ”

It is not known how many residents are illegal immigrants, but the number is thought to be substantial. The community continues to be a traditional immigrant point of entry, especially for new arrivals from Mexico and Central America, who sometimes encounter resentment from those already here. The friction between newcomers and established residents can be caused by competition for already scarce jobs—or simply the struggle for equal social status.

The latter is evident at the predominantly Latino Roosevelt High School, where some students who speak English and some who do not gather at opposite sides of the campus. “They (English-speaking students) criticize us and laugh at our English,” said 15-year-old Nancy Silva, who moved here from Mexico three years ago. Added another, “They think they are better than us . . . They call us wetbacks, rancheros, mojados and TJs.”

Whether Boyle Heights can survive as it is today—gateway for new arrivals and haven for much of the city’s less affluent Latino population—is an open question in the minds of some community leaders. They wonder whether the community’s proximity to downtown will someday make it appealing to up-scale developers, leading to displacement of most of the people who now call Boyle Heights home.

“lt may seem like paranoia to some people,” said Dolores Sanchez, editor and publisher of Eastern Group Publications, which distributes seven news—papers geared toward the Eastside residents, “but we remember the freeways, Chavez Ravine and Bunker

Hill . . . where Latino communities were wiped off the face of the Earth.”

Father Pedro Villarroya, a key member of the United Neighborhoods Organization, agreed.

“Boyle Heights is a pearl that nobody has noticed, a land of opportunity,” said Villarroya, placing a clenched fist on the center of a Los Angeles map laid out on his desk at Our Lady of the Rosary of Talpa Church. “Because they have built up so much here,” he said, moving his fist from west to east on the map, “they’ll have to move this way.”

The existing zoning for the area, which dates back to 1946, until recently was regarded by preservationists as part of the problem. It permits high-rise apartment development on 755 of the residential land and could send the population soaring from its present 88,000 to 140,000.

But Raul Escobedo, who drafted a 20-year plan for Boyle Heights adopted by the City Council in 1979, said the council is in the process of rolling back zoning in the area, as recommended in the plan. The rollback, he said, is intended to preserve “existing one- and two-family housing, street capacities and available public services” and could go a long way toward alleviating fears of massive development in the foreseeable future.

“We’ll never become upper- or middle-middle-class because of the old homes,” said Councilman Arthur K. Snyder, who represents the area. “Those wanting large, new homes will go elsewhere. The people who like to live in this ambiance are going to stay. . I resist every demolition.”

There are no visible signs that large-scale development will occur in the near future, but many old-timers here still recall the “demolitions” of past years.

During World War II, industry began expanding around the nexus of rail lines in downtown Los Angeles, eventually gobbling up one-fourth of Boyle Heights’western and southern flanks. Three federal public housing projects-Aliso Village, Pico Gardens and Estrada Courts-erected in the flatlands during the same period took up more land.

All built in 1942, the run-down apartment units now house about 6,000 of the area’s poorest residents.

There are few amenities. Social services and a permanent security force are lacking. The din from nearby freeways and industrial areas is constant. Some residents complain that crime and drug trafficking flourish.

From the window of their $174-a-month Aliso Village apartment, Beatrice Zamudio keeps a close watch on her children. Dangerous influences, she said, abound beyond the door.

“Sometimes,” she confided, “when people are smoking marijuana outside, I have to shut the doors and windows because the smoke comes in and fills the rooms.”

In summer, she added, “it is very hard. I have seven children. I can’t keep them indoors all the time.”

Residents opposed the construction of five major freeway systems over a 35-year period but were powerless to stop them.

The San Bernardino Freeway opened in 1943, followed by the Santa Ana, the Golden State, Santa Monica and Pomona freeways and a complex series of interchanges. The freeway system ended up taking 12% of the available land in Boyle Heights.

“When you look at the freeways you can get really depressed,” said Escobedo, now with the Boyle Heights Community Redevelopment Agency. “Heck, every one of them was protested, but there was an engineering attitude that prevailed. Look at the East L.A. Interchange. It’s a mess, but they were proud of those things then.”

Chicano historian Rodolfo Acuna has described the history of freeway construction through Boyle Heights and East Los Angeles as one of “plunder, fraud and utter disregard for the lives and welfare of people.”

At Lorena Street Elementary School, teachers and students cope daily with overcrowded conditions and the depressing effects of freeway noise and pollution.

Built in 1913, the 3.7-acre school is devoid of parking space for teachers and parents and butts up against adjacent single-family dwellings. It was originally intended to serve 200 to 300 students, but an average of 860 children are jammed into classrooms and newly installed portable buildings, which drastically reduce playground space.

Principal Paul Yakota said the problem of freeway noise was at least partially remedied a few years ago when a wall to deflect sound was erected at the school’s southern boundary-the Santa Ana Freeway.

Now the school is in desperate need of a cafeteria.

“The problem,” Yakota said, “is that the powers that be have never been out here to see for themselves.”

The grade schools in Boyle Heights feed into 50-year-old Roosevelt High, one of the strongest unifying elements in the community.

“I have two basic goals,” new principal Henry Ronquillo told students soon after taking over in January. “One is to do my best as principal to make sure you get the best possible education. The other is for Roosevelt to beat Garfield High School in football next November.”

The rivalry between Roosevelt and Garfield High, four miles to the east, has become legendary. The November grudge match draws an average of 24,000 spectators each year, many of them alumni from around the world.

“No high school in the nation can boast that kind of a crowd,” Ronquillo said to rousing applause.

In the midst of problems that one city official calls “mind-bogglingi’ some who live in Boyle Heights are doing for the community what municipal government will not or cannot do.

Manuel Orozco left a ranch in Zacatecas, Mexico, 10 years ago and bought a modest home next to Sheridan Street Elementary School. About six months ago, he noticed that trash was piling up in the streets around the school. He asked the principal why it was not cleaned up.

“She said there wasn’t enough city personnel to do the work (on a regular basis) because of cutbacks in funds,” Orozco recalled. “I said we don’t need the city to do it if everybody helps.”

Orozco helped organize a crew of volunteers from the neighborhood to sweep the streets around the school. What began as a one-time cleanup became a weekly routine.

In June, Sheridan Street School parents met with Councilman Snyder to complain about the dirty streets. Snyder expedited the resumption of the city’s street-sweeping program in the area.

Volunteer participation is a key ingredient at Boyle Height’s Hollenbeck Youth Center, one of the largest privately funded recreation centers in the city. About 250 small business owners donate $120 each year to keep it operating, and many of its regularly scheduled activities, such as boxing, are supervised by police officers who volunteer their services.

One boxer, Paul Gonzales, 18, who lives in the Aliso Village housing project with his mother and seven brothers and sisters, became one of this country’s top Olympic flyweight prospects when he defeated the Soviet Union’s Olympic champion, Shamil Sabryov, at Syracuse in early March.

Many residents and business owners bitterly complain that positive trends in the community are ignored by the media. “We have to beg for everything we get,” said Linda Orozco, manager of the Boyle Heights Chamber of Commerce. “It is depressing to the point of tears. Nobody cares about us. Even the press only comes out if someone gets shot.”

There has been no lack of media coverage about Snyder, the area’s controversial councilman, who has survived a love/hate relationship with constituents in Boyle Heights for the last 16 years.

Many in Boyle Heights believe that it would be politically and symbolically important to have the area represented by a Latino. There has not been a Latino on the City Council since Roybal left that post in 1962.

Snyder has many supporters in Boyle Heights who Laud his efforts—many of them successful—to upgrade the community with more street lights, trees, senior citizens centers and libraries. But privately,some prominent community figures also fear Snyder’s power.

“I have to support Art Snyder, otherwise he’ll hurt us,” said one businessman, who asked to remain anonymous. “He’ll stop us from getting funds for (commercial redevelopment) projects . . . The people of Boyle Heights have been brainwashed into thinking he is the great white god.”

Steven Rodriguez outpolled Snyder by about 800 votes in Boyle Heights in the April election. But Snyder managed to get enough votes in other areas of the district to win.

The common perception about Boyle Heights is that it is a dangerous place to live.

But Hollenbeck Division, which encompasses the heavily Latino areas of Boyle Heights, Lincoln Heights, El Sereno and Montecito Heights, had the fewest major crimes reported on a per capita basis among the city’s 18 police divisions, according to 1982 Los Angeles police statistics.

“You may not want to live here because it is not new,” said Hollenbeck Division Capt. Joe Sandoval, “but it is one of the safest areas in the city.” However, some law enforcement authorities believe that some crimes go unreported by undocumented immigrants fearful of being deported.

There may be fewer crimes reported on the Eastside, but drug abuse problems abound. Among the

city’s 18 divisions, Hollenbeck was second last year with 2,010 narcotics-related arrests-about 11.9% of the city’s total.

Steven Friedman, psychologist and director of the federally funded El Centro Substance Abuse Treatment Center in Boyle Heights, suggested that the widespread abuse of drugs goes with the territory.

“It is the cheapest way to forget how lousy life is for the longest period of time,” he said.

Only five of the 30 homicides reported in Hollenbeck Division last year were gang-related. Nevertheless, gang violence is a harsh reality that residents struggle to deal with in a variety of ways. When it happens, it tears families apart and cuts down youths in their prime. Drive-by shootings sometimes take the lives of innocent bystanders.

Rafaela Roman, 58, still trembles at the memory of a summer afternoon a few years ago. She was washing clothes in her apartment when she heard the pop of gunshots in the distance, then an ambulance siren, then a knock at the door.

“Two boys said, ‘Don’t be afraid, we just want to tell you they just shot your son, Arthur,”’ Roman recalled, fighting back tears. “l ran into the street and fell on my knees three times . . my legs felt so weak.” She collapsed a fourth time at the feet of detectives a block away. They told her that a bullet fired by unknown assailants in a passing car had lodged in Arthur’s spine.

Arthur recovered, only to be implicated later in a gang-related shooting incident. He was sent to the California Correctional Facility at Susanville.

Arthur’s older brother, Octaviano, died of a drug overdose last year.

From 3% to 5% of the Latino youths in East Los Angeles belong at one time or another to street gangs, according to Armando Morales, a UCLA Department of Psychiatry social worker who has spent 10 years studying the phenomenon. Morales believes it is a natural and desperate response to oppressive conditions in the barrio—sometimes with oppressive consequences of its own.

In his “History of Boyle Heights” class, Roosevelt teacher Howard Shorr has tried to present his students with a clear understanding of the community and how it got that way. The anecdotes and facts that they learn can have a telling effect.

“There are a lot of things around here I’m not proud of,” one of Shorr’s students, Lorena Jimenez, 17, said, after class. But Jimenez, who works with senior citizens in her spare time, is determined to “go to college, come back here and help change things’”

Like many minority, working-class communities, Boyle Heights was hard hit by the recession. There is no accurate measure of unemployment because the area is too small to be measured separately, but one state analyst thinks that the rate could run as high as 25%.

Unemployment is a topic frequently discussed at Paul Bercerra’s small barber shop on Brooklyn Avenue, a place where residents have been sharing their sorrows and joys for 27 years.

“There are-many hard-working people here from Mexico who need jobs,” said Bercerra, 59, sharpening a straight razor in his crowded shop while counting off a list of problems in the community.

“Neighborhoods are deteriorating, streets need cleaning, education has gone to the dogs and there is no place to park,” Bercerra said. “I think the area has gone from bad to worse. Most of the people I grew up with have moved to Montebello, Monterey Park, South Gate.”

Denise Sherlock, 27, a Latina born and raised in Boyle Heights, had brought her 6-year-old son in for a haircut.

“What about the positive things!” she said’ “There is more warmth here as far as neighbors go. I doubt if they (neighbors) even speak to each other on the Westside.”

“Yes.” Bercerra nodded in agreement.

“In my neighborhood I see a lot of pride and very little crime,” added Sherlock.

Neither Bercerra nor Sherlock ventured to predict what shape the community will be in 20 years from now.

But Boyle Heights businessman Art Chayra, in an interview later, was optimistic about the future.

Chayra said he went to the installation of Larry Gonzalez on the Los Angeles school board and sat among dozens of Latino politicians, judges, lawyers and educators assembled at Roosevelt High School cafeteria to witness the ceremony. Many, like Gonzalez, were products of Boyle Heights.

‘I was sitting among peers who made it big and were sticking by the community,” Chayra said’ “I felt as though a new age was coming. All around me I saw a new watershed of talent that was growing in Boyle Heights and East Los Angeles and I could see the power it was getting.”

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.