‘A box full of ethnic labels’

When Leobardo Estrada was growing up in Texas in the 1950s, he and his family called themselves Latin-Americans. Later in school, teachers referred to him as Spanish-American, Mexican-American or Spanish-surnamed.

In college during the late 1960s, he called himself a Chicano.

When he worked for the 1980 Census, one of his assignments was to make sure that Spanish-origin people were accurately counted.

“I felt like I was traveling around the country (for the Census Bureau) with a box full of ethnic labels,” Estrada said. “I kept crossing out the ethnic terms in my speech and replacing Hispanic, Latino or Chicano with the appropriate term for each audience.”

Estrada, now a UCLA professor, is not alone in these experiences. Few groups have had as many ethnic identifying terms over the years as Latinos. Many non-Latinos often ask apologetically when talking to Latinos: “What is the term now...?”

Individuals Latinos know what they call themselves and how they want others to refer to them. But for historical reasons, there is no agreement on what to call the entire Latino community. Various terms have come into use in different areas.

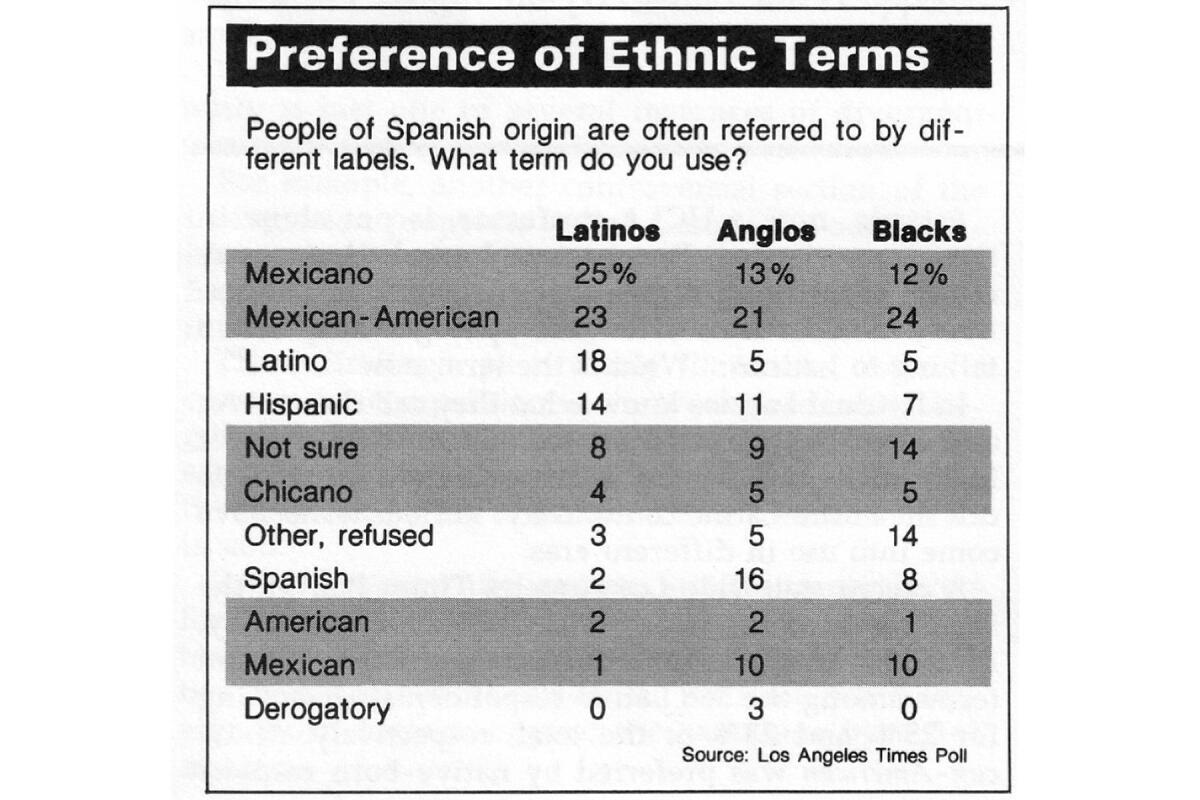

A recent statewide Los Angeles Times Poll on the issue revealed the wide variety of terms used today. Mexicano and Mexican-American were the favored terms among the 568 Latino respondents, accounting for 25% and 23% of the total, respectively. Mexican-American was preferred by native-born respondents of Mexican descent, while Mexicano was the first choice of foreign-born respondents.

Latino and Hispanic, two general terms for the entire U.S. Spanish-surnamed population, were next with 18% and 14%, respectively.

The term Chicano was preferred by only 7% of native-born Latinos and 4% overall. People preferring this label tended to be those born in California, under 30 years of age and with a college education.

The origin of the term Chicano is unknown but it apparently derives from Mexicano. It was once used by the upper class in Mexico as a derisive term to refer to the lower class. It became popular on U.S. college campuses during the 1960s when many students adopted it as a sign of ethnic pride and political defiance.

When Chicano came into vogue, it drew opposition and even hostility from some older and conservative Mexican-Americans. It was not uncommon in the 1960s and early 70s for Chicano activists to shout Chicano power during demonstrations and yet go home and be forbidden by their parents to use the term.

It is still in fairly extensive conversational use among younger Mexican-Americans and still packs an emotional appeal for them. Chicano and Mexican-American now have essentially the same meaning, but Chicano implies a more politically active person.

The label Latino is becoming increasingly popular and useful because it refers to all Spanish-speaking people in the nation, including Mexican-Americans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Mexicans and others of Latin-American descent.

Latino is preferred by some because it is a term that grew out of the community itself, said Estrada, now a demographer in the UCLA Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning.

On the other hand, Hispanics is a noun born in the federal bureaucracy in Washington. In the mid 1970s, federal officials met periodically in the conference room of the U.S. secretary of education to decide what term to use for the Latino population and other U.S. ethnic groups.

“I think that every term was brought forth for discussion and was basically rejected,” said Estrada, who participated in some sessions as a Census Bureau representative. “The one term that survived and was adopted was Hispanic.”

Estrada called the long sessions “one of the few times when government has sat down and debated on what to call somebody and imposed that word on them.

“If at that time, you had gone to any Chicano gathering and said, ‘Will all the Hispanics stand up; there would have been confusion and questions of ‘Who do you mean?’ ”

Since then, the term Hispanic has been picking up steam. Besides its use in all U.S. government publications and reports, it has been used by business executives eagerly exploring the “Hispanic market’s potential” and politicians courting the “Hispanic vote.”

Hispanic has been adopted by some National or East Coast-based media. The Times, some other newspapers and numerous magazines published by members of the community use the term Latino.

The wide variety of terms reflects ‘Latinos’ changing perceptions of themselves and how they are seen by others.

During a period of harsh discrimination a generation ago, the term Mexican was often used in a derogatory tone. “If you wanted to express what you were and didn’t want to use the word Mexican, Latin-American and Spanish-American were alternatives,” Estrada said.

Hangovers from that period still linger. Although most Mexicans and Mexican-Americans feel comfortable about the term now, some Anglos are not. The use of the term Spanish persists among Anglos who somehow consider it euphemistically preferable to Mexican.

At the same time, Latinos’ perception of their race is apparently changing.

Although cultural anthropologists consider Latinos white, about half of the Latinos in California and nationwide did not identify themselves as white in the 1980 Census questionnaire.

Instead, those Latinos, particularly Mexican-Americans, entered other and wrote in answers on the Census forms stating that they were Mexican-American, brown or some other Latino designation.

Most Latinos are a mestizo, or mixed, race with varying degrees of Spanish and American Indian blood.

“Latinos raised the issue of a nationality to a level of race,” Estrada said. “They took the word Mexican and Latino or Hispanic and treated it as if it were a race like black and like white.

“What they were saying,” Estrada added, “is that anthropologists may call them white. But they don’t see themselves as white and Anglo society does not consider them white. So they identify more with being Mexican or Latino.”

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.