With less money and more risk, waves of child-care providers call it quits

OAKLAND — Kirsten Hove and her mom have been taking care of kids in San Francisco for decades.

Hove’s mother opened a day-care program in her home in the city’s Marina neighborhood more than 30 years ago. In 2006, Hove and a family friend expanded the business by opening sites in their apartments nearby. The days were long, but the women loved the work.

What took years to build, however, was dismantled by the coronavirus in just a few months.

When Californians were ordered to shelter in place in March, Hove, her mother and their friend were forced to close completely for a week and then reopened with only online programs. Half of their families dropped out, and many of those that remained paid far less than the usual $2,600 monthly fee.

In May, as the financial strain mounted, the women were allowed to bring children back into their homes. But several people on their staff were nervous about returning to work as the number of infections continued to climb.

They felt they had no choice but to close two of their sites, keeping only the original location open.

“I really had no idea how bad this pandemic would be,” Hove said. “I thought we’d go in shelter in place and it would be over and we’d reopen again.”

Hove’s experience reflects a tough reality playing out across California.

Since the coronavirus shut down the state in mid-March, financial losses, concerns about exposure to the virus and navigating a maze of new safety guidelines have forced some 9,300 licensed child-care providers — almost 1 of every 4 in the state — to close, according to data from the California Department of Social Services that show closures through July 31.

More than 1,200 of the closings are permanent, eliminating roughly 19,000 child-care spots, the state figures show. There is no way to know how many of the thousands of others that have shut their doors during the pandemic will eventually reopen or when, leaving the full effect of pandemic on child care uncertain. A recent survey by the Center for American Progress estimated that California was at risk of losing more than half of its available child-care slots.

In the early, chaotic weeks of the pandemic, advocates and providers pointed to the likelihood of a wave of child-care closures like the one now playing out. The rash of closings underscores the toll the pandemic is taking on family life in California.

Experts warn the decline of child-care spots has enormous implications for how well and how quickly individual families and the state’s economy as a whole will be able to recover from the pandemic. The effect is particularly acute for women of color, many of whom own and work in child-care centers, and mothers, who are often left to juggle the demands of child care and work.

“It’s going to be really challenging to support an economic recovery in the state if parents can’t get to work on a consistent basis,” said Lea Austin, executive director at UC Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. “We can expect that this is going to undermine the ability of women to return to work.”

Most child-care businesses in the state are small, home-based operations like Hove’s. They have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic, accounting for slightly more than 80% of the permanent closures, according to the state data.

The loss of child-care spots has not been spread evenly across California, with rural counties in the northern part of the state seeing more closures than more urban areas, according to county-level figures from the state that show permanent closures through July 7.

Marin and Del Norte counties proportionately have seen the most permanent closures in the state, losing roughly 15 child-care slots for every 1,000 children younger than 5, according to state figures. Alameda County lost 11 spots, followed by Yolo and Colusa at nine.

Southern California fared relatively better. San Diego and Los Angeles counties, for example, lost seven and three slots, respectively, for every 1,000 children. Families in Los Angeles have been hit hard in other ways, however, as public preschool programs have struggled to meet the needs of the poor communities they serve.

The number of child-care spots that have disappeared during the pandemic is significantly higher since the county-level figures do not include providers that may eventually reopen.

The reason for each closure is not included in the state data, but a survey of more than 900 child-care providers conducted last month found that concerns about exposure to the virus were behind at least three-quarters of home-based closures during the pandemic.

The current spate of closures has accelerated a trend that began in 2007 with the country’s housing crisis and economic recession. Between 2008 and 2016, the number of home-based child-care centers in the state dropped by almost 30%, as they struggled to compete with a growing number of public prekindergarten school programs and remain economically viable while often serving lower-income families and operating on thin profit margins.

While the pandemic has forced child-care operators across the U.S. to fold, California is feeling the pinch acutely. Even before COVID-19, 60% of Californians lived in areas that lacked adequate access to child care, often referred to as child-care deserts.

“The long-term picture without some public intervention, both in terms of policies and resources, is very troubling and very bleak,” Austin said of the child-care offerings in the state.

The pandemic has left child-care providers with two bad options: closing and joining the ranks of the unemployed at a time of deep uncertainty for the U.S. economy, or remaining open and putting themselves and their families at risk of exposure to the virus.

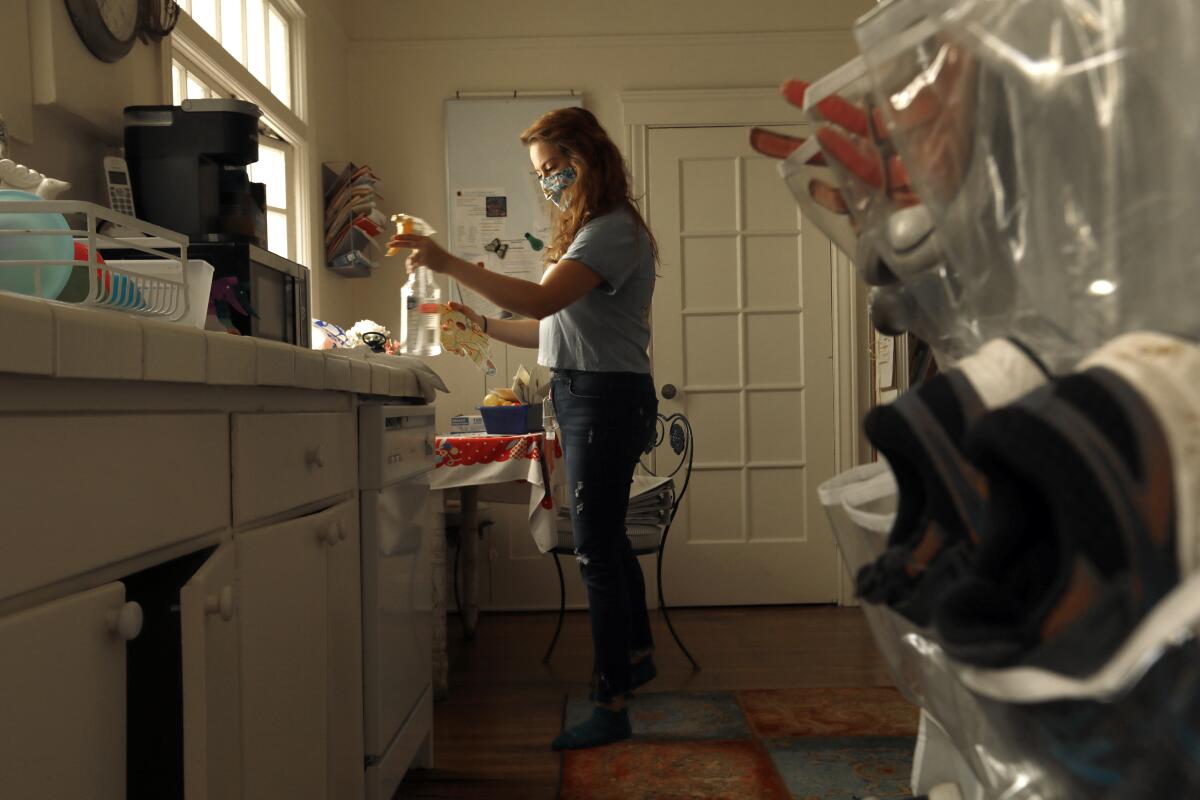

Jennifer Araiza cares for about a dozen kids each day at her Grand Terrace home in San Bernardino County. To guard against the virus, she estimates she has spent about two hours each day sanitizing and an additional four hours doing deeper cleans every weekend. She goes through supplies so quickly that, for a time, she was making her own disinfectant from water, alcohol and a few drops of essential oils.

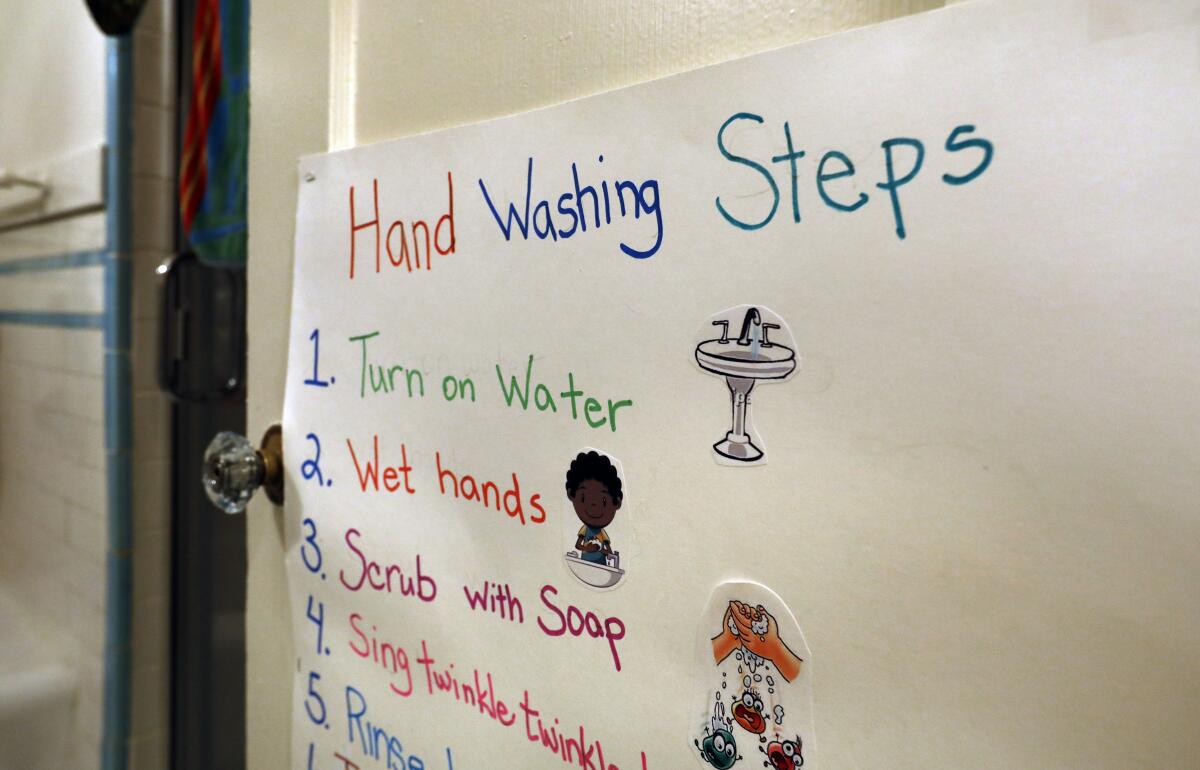

The cleaning regimen is part of a broad set of guidelines put out by the state that call on child-care providers to implement a range of enhanced safety measures to protect against the virus, including social distancing, health screenings and specific procedures for how parents drop off and pick up their children.

“At this point, we’re working about 12-hour days Monday through Friday and on off hours we’re required to sanitize,” Araiza said. “It’s nonstop. It’s tiring.”

Araiza spent weeks weighing whether to remain open, deciding recently to scale back to just two days a week and to work part-time as a teacher elsewhere. “The demands,” she said, “are a little more than we can bear.”

California Gov. Gavin Newsom waived some bureaucratic requirements to make it easier for providers to remain open, and the Department of Social Services has started to allow emergency “pop-up” child-care facilities to help fill gaps during the pandemic. But those steps are unlikely to make up for the wave of closures.

Some providers have found help elsewhere. . Hove, for example, received a $90,000 loan in May through the federal Paycheck Protection Program, which she said allowed her to continue paying teachers at their regular salaries. But she was one of only a few thousand child-care providers in California to receive a loan — less than 1% of all of the loans issued in the state, government figures show.

“We have the historic undervaluing of women’s work and the undervaluing of work performed by people of color combining to create this workforce that really is just overlooked,” said Austin of UC Berkeley.

For Hove, her mom and their friend, the strain of keeping all three locations open through the pandemic was too much. Cleaning supplies alone were costing her an additional $200 a week and neighbors were unhappy about the increased risk of exposure that came with a day care next door.

“I feel a great sense of sadness and loss,” said Hove, who was moved to tears as she talked about scaling down the business they had built. “This business has supported me and my success. We have over a decade of children whose lives we’ve impacted.”

Sharma Rani is a journalist with the Fuller Project, a global nonprofit journalism newsroom reporting on issues that affect women.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.