It’s déjà vu in the Bay Area as fires again force evacuations and cloud the skies

HEALDSBURG, Calif. — Fires across California continued to expand Thursday, most critically in the North Bay and Santa Cruz mountains, propelled by erratic winds near the coast and hampered by resources stretched thin by dozens of blazes.

From the Salinas Valley to wine country, smoke as thick as fog in some places made it feel as if flames were everywhere. Thousands fled to shelters and hotels, the pandemic ever present but posing a distant risk compared to fire. In the Sonoma County town of Healdsburg, under an evacuation warning, residents prepared to leave, some for the third time in four years.

So many fires burned in the numerous low mountain ranges surrounding the San Francisco Bay that the region was home to the world’s worst air quality Wednesday night and Thursday morning, according to the website PurpleAir.

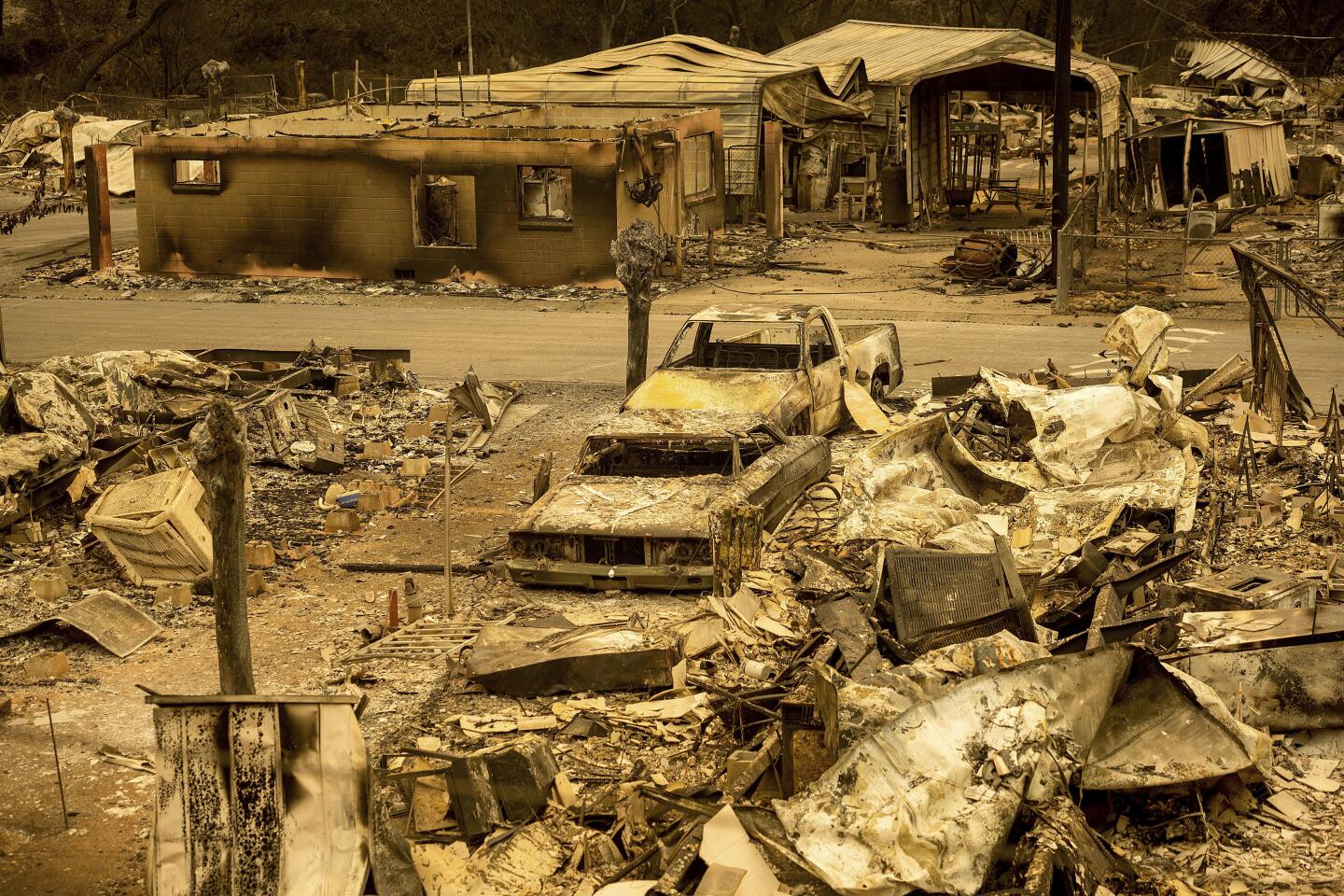

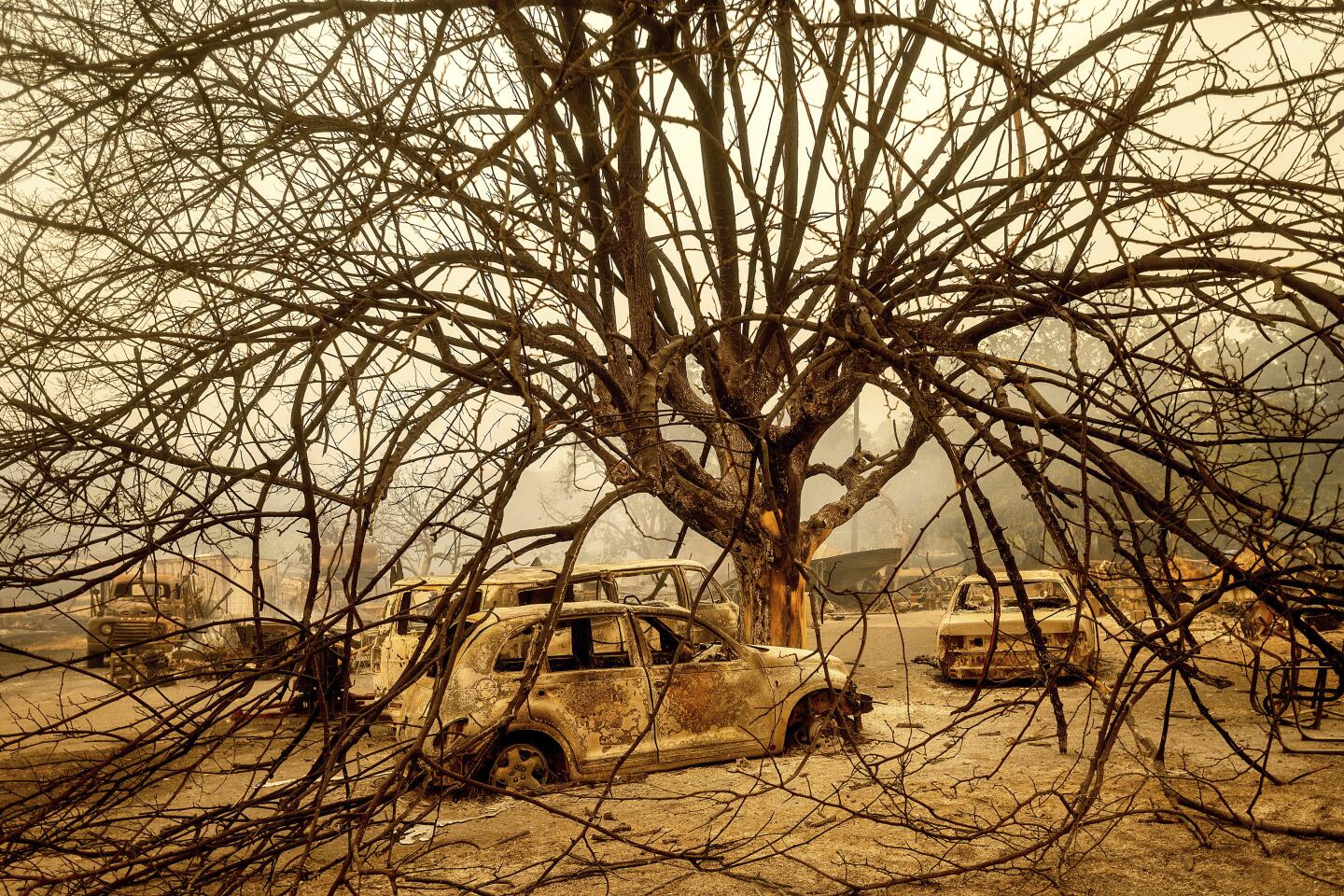

In all, more than 700,000 acres have burned in Northern and Central California, displacing more than 60,000 people. At least 134 structures have been destroyed, and while the combination of heat and wind eased slightly Thursday, it is not expected to taper off soon.

“In the past four days, there have been over 370 new wildfires, “said Daniel Berlant, a Cal Fire information officer, “with two dozen of the major fires still burning in California.”

Flames reared up in communities from the dry hills west of the San Joaquin Valley to the edge of San Jose, nearing the famed Lick Observatory, which serves astronomers from the University of California.

They threatened small coastal hamlets, such as Jenner and Davenport, which are far more often beset by fog and brisk ocean breezes.

Late Thursday, authorities ordered the evacuation of UC Santa, a campus that typically educates more than 18,000 students. Those on campus were urged to go to the city’s beach boardwalk.

Just to the east, winds drove fire deep into the redwood forest of the Santa Cruz Mountains, causing extensive damage at Big Basin Redwoods State Park, California’s oldest.

“We are devastated to report that Big Basin State Park, as we have known it, loved it, and cherished it for generations, is gone,” tweeted the Sempervirens Fund, a group dedicated to protecting the local redwoods.

California’s oldest state park has suffered extensive damage from the C.Z.U. August Lightning Complex fires.

“I couldn’t stress more the importance of leaving when those orders come out, I really can’t,” Santa Cruz County Sheriff’s Chief Deputy Chris Clark said during a briefing Thursday. “There are people that are unaccounted for that we are looking to try to determine where they are, so I stress that because, with this fire, you just don’t know how things are going to go.”

The multitude of ignitions were mostly sparked by a freak summer lightning storm Sunday, which hit at the worst possible time, when the grass and brush were at their driest.

Southern California also broiled under a scrim of smoke, converging from several fires started last week, mainly the Apple Fire in Riverside County, and the Lake Fire in the Angeles National Forest.

But the bad air was nothing like the acrid clouds smothering Northern California — the worst of it in the Silicon Valley.

“Smoky and hazy conditions are likely to impact portions of the region through at least this upcoming weekend,” the National Weather Service said.

Experts advised staying indoors if possible, and wearing a mask diligently outside — for both the smoke and the coronavirus, which can be spread by coughing.

In the North Bay area, it was the sense of déjà vu that was most dispiriting. From Fairfield and Vacaville west to the Napa and Sonoma valleys, the region has been devastated repeatedly since 2017 by catastrophic blazes.

On Thursday, Harvest Echols was tired of running from fire, tired of packing up her kids, tired of this wine country town that seems to come close to burning every year. Now faced with her third fire evacuation, she is, she said — as she tried not to cry — “just trying to keep it together.”

That meant packing up the dark gray trailer she and her husband, Healdsburg vice mayor Shaun McCaffery, bought just before the pandemic in preparation for the moment that is becoming about as predictable as Labor Day or Halloween: evacuation day.

For the last three years, Sonoma’s inhabitants have been forced out by flames as wildfire season seems to grow stronger and longer.

Echols remembers the middle-of-the-night run she had to do last October when the Kincade fire was close enough that its orange glow crested the nearby hills. Then, she and her two kids, Leo, 14 and Lili, 12, left McCaffery behind to guard the house and headed to a hotel in Sebastapol.

But within hours, pounding on their door alerted them that the hotel was in danger of burning. They fled again, through dark country roads jammed with traffic, finally sleeping in their car in the parking lot of the Santa Rosa fairgrounds.

Two years before that, the deadly Tubbs fire sent them running. They drove hours of winding roads to the coast, renting the only house they could find in Ft. Bragg, a “mansion” that she thinks must have cost a fortune, but was all they could find. McCaffery still hasn’t told her how much they spent.

Fires raging in Northern and Central California are forcing thousands from their homes and turning the air into an increasing health hazard.

And though the Camp fire in Paradise in 2018 wasn’t close enough to force them out, it brought its own trauma. A thick smoke settled on Healdsburg, casting them in the dark for days, she said, and leaving her thinking about the dead as she breathed that air.

“To know all those bodies were burned up in there was horrible,” she said.

Fire experts say the North Bay has been hit hard in recent years partly because of PG&E’s power equipment failures but also because of a warmer climate and an influx of invasive species. These include an exotic plant called ripgut brome grass, which has moved into the oak woodlands, said Don Hankins, a geography and planning professor at Chico State University.

Much of the region was little-touched by fire prior to 2015, making it more flammable, others note. Within the region, the area scorched by fire between 2015 and 2018 amounted to 50% of what had burned there in the previous 65 years, said John Abatzoglou, an associate professor in UC Merced’s school of engineering.

Californians may have to get used to it. “I don’t see a future where we’re going to return to many smoke-free years in a row again,” he said.

For the Echols family, the wind mercifully stalled Thursday, allowing them time for an organized retreat.

After last year’s evacuation, both kids missed weeks of school. Echols feels like it’s adding up.

“They miss their friends, they miss school, they miss normalcy,” said McCaffery.

McCaffery said their anxiety is becoming normal this time of year in wine country, when the dry grass starts rasping in the wind. “It just kind of wears on people that they might have to go,” he said. “It’s just triggering that emotional reaction in everyone that this is a danger.”

Gabriela Orantes volunteers to help vulnerable Latino workers during the fires. When the Kincade hit last year, she spent 12-hour days for a week at the evacuation center in Petaluma, acting as a translator for the many workers who speak not only Spanish, but also indigenous languages that often leave them with little information in an emergency, she said.

She is “dismayed,” she said, that although many in the Latino community have been forced to evacuate four or even five times in recent years, there is still what she believes to be insufficient outreach to ensure their safety. “We’ve learned that we can’t count on the county messaging or the city messaging to be accurate,” when it comes to translations, she said. “It still feels like we are learning every time.”

Just off the town square, Ann Foster and her daughter Molly sat at an outdoor table at Williamson Wine eating truffled gouda and drinking pinot noir as ash swirled like snowflakes. It was a bit of time together before Molly moves to Spokane.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The elder Foster evacuated from the two fires before this and was wondering how much more she could take. “If you asked me last night, I was ready to retire and move to the Pacific Northwest,” she said.

Around the corner, Gina Gandeza smoked a cigarette in front of her apartment complex. She too evacuated last year and would have left last night, but her two adult daughters work at businesses that are still open — a gas station and a convenience store. Those places won’t close until there is a mandatory evacuation order, she said, and she won’t leave without them.

Her car was packed and though she said Healdsburg will remain her home, she knew many locals were tired of this annual run.

“A lot of people have been talking about Oregon lately,” she said.

Staff writers Rong-Gong Lin II, Leila Miller and Luke Money contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.