Under a large canopy in the parking lot of the Continental Funeral Home in East Los Angeles, more than two dozen folding chairs carefully placed several feet apart faced the cherrywood casket of 59-year-old Felipe Juarez.

Juarez died of COVID-19 last month, four days after the same disease killed his younger brother. And a month after it took the life of his sister in Mexico.

After such an unspeakable series of losses, the family felt forced to settle for a funeral that was nothing if not surreal. Family members had gathered to say their goodbyes amid the melodic chime of a passing ice cream truck and the noise of rush hour traffic on Beverly Boulevard.

Philip Juarez, 31, felt like he was disrespecting his father, but he knew the pandemic left the family no choice. Still, he said, “it’s hard to accept.”

The novel coronavirus has ravaged California’s Latino communities, with many people who are front-line workers catching COVID-19 and then spreading the disease to family and neighbors.

This grim cycle of illness and death ends at places like Continental Funeral Home. Mortuaries that serve Latino communities have been overwhelmed by families in need of help since March, with bodies in some cases stacking up as operators tried to improvise funerals that previously might have drawn extended family and mourners from far and wide.

The Juarez family was relatively fortunate because it was able to hold a small service outdoors. Earlier in the pandemic, some people had to beg health officials to allow them to have funerals for their parents.

“It’s been so difficult for the families,” said Magda Maldonado, director of the funeral home. “They have been unable to express their condolences properly or participate in service.”

In California, Latinos make up 39% of the state’s population but account for 59% of COVID-19 infections and 47% of deaths, according to the state Department of Public Health. Immigrants have been particularly hard-hit economically amid the pandemic, with many losing their jobs and facing financial collapse.

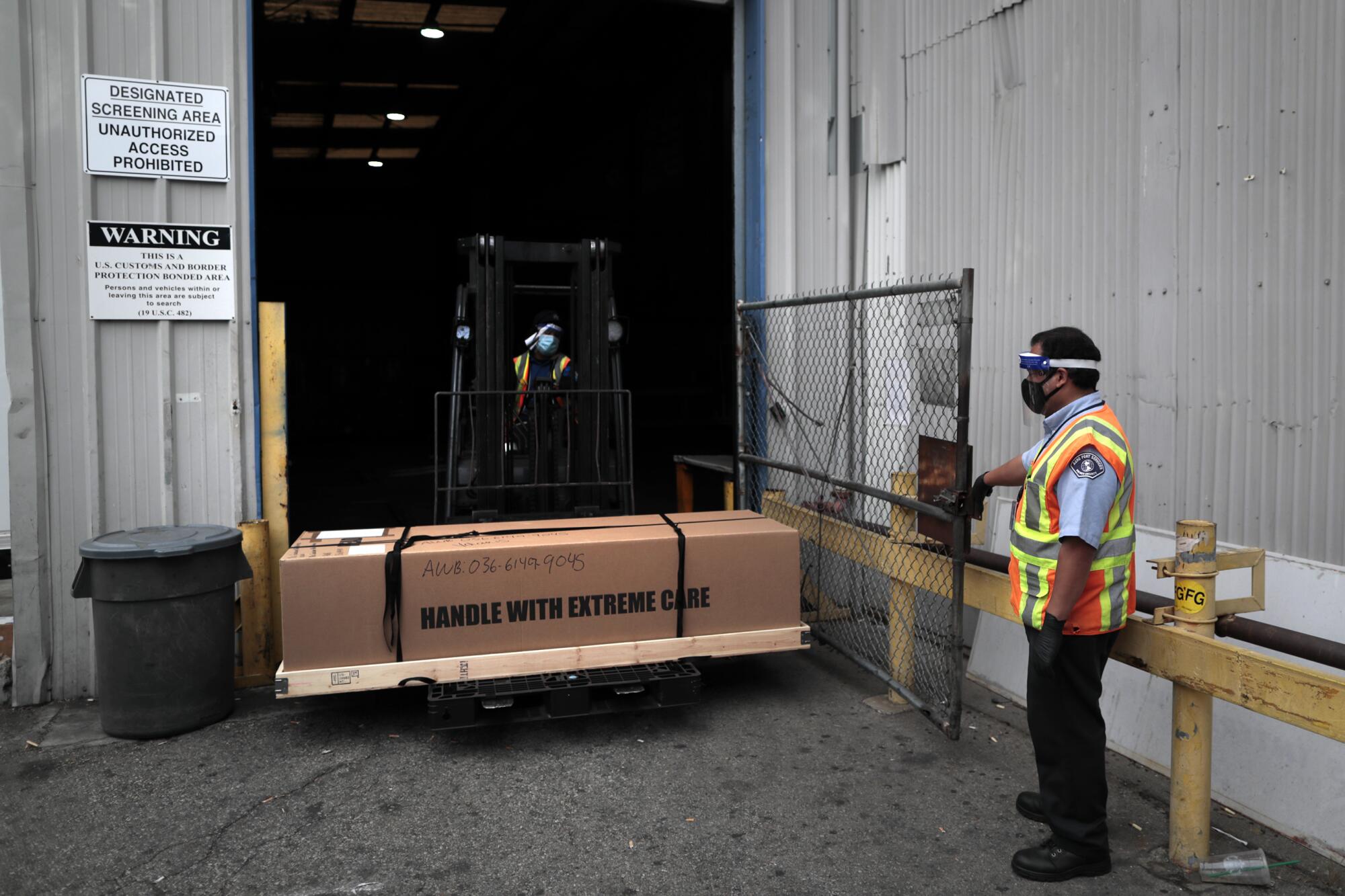

Maldonado sees these hardships at her funeral home. Most of her clients are immigrants from Mexico and Central America, and 60% of her business is devoted to transporting bodies to their homelands because it’s less expensive to bury loved ones there.

When the coronavirus outbreak hit, a flood of bodies was sent to Maldonado’s funeral home. The cold storage could hold only up to 25 at a time.

“We were dealing with 35 to 40 bodies at one point in the month of March,” she said.

To handle the overflow, she rented a small refrigerated storage container for $1,900 a month, which increased the funeral home’s capacity to about 55 bodies. It also helped separate the bodies of people who died of complications from COVID-19 from those who died of other causes.

She said capacity problems had more to do with the shutdowns. Required paperwork from state and county offices that once took a few days was taking weeks. The process to send a body back to Mexico stretched from a previous 10 days to two months. Cremations that once took a day now had to be made by appointments.

“It really caught us all off guard,” Maldonado said. “Local governments didn’t know how to really manage this kind of emergency, and I don’t think anyone thought about all these other funeral problems we’d have.”

The pandemic has increased operating costs for Maldonado, which in turn hurts the families she’s been trying to serve. The cost of transporting a body to Michoacan, Mexico, for example could grow to $4,200; in the past she could shave off about $1,500 if the family could not pay the full amount. But now, she has reserved those discounts for only the neediest of families or consulates that are assisting people.

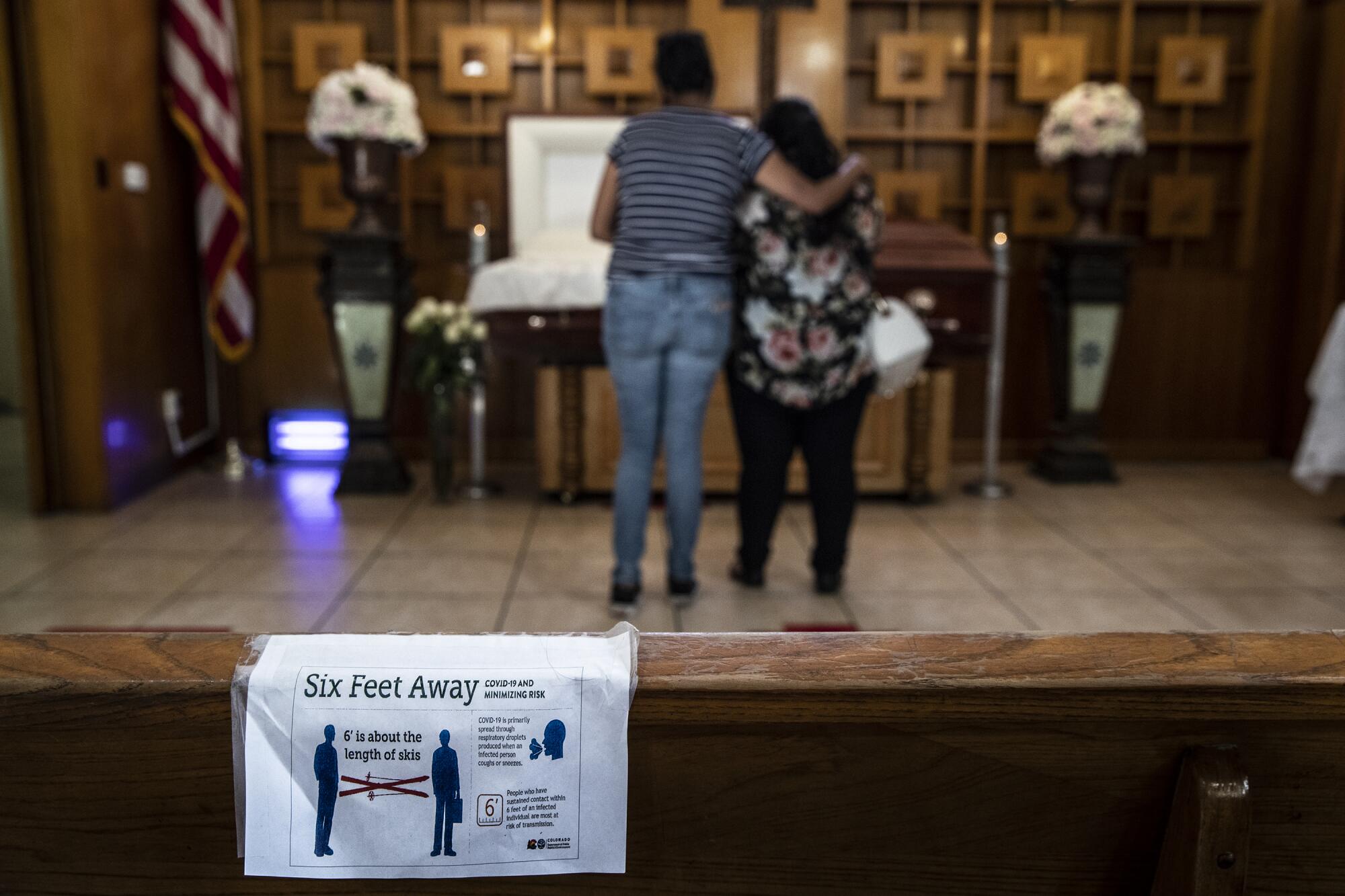

But the biggest challenge facing funeral homes is basic: How to give families a chance to mourn loved ones while keeping those who attend the funerals from getting sick.

Bob Achermann, executive director of the California Funeral Directors Assn., said funeral homes were relying on guidance from the state — but it became confusing to follow at times.

“The rules were sometimes changing from week to week, location to location,” he said. “When there were services, only 25% of the space could be occupied and that you were social distancing.”

“How do you not hug? How do you not touch during, you know, those those times of grief?” he added.

Several minutes before the Juarez family arrived, past rows of empty pews inside the Continental Funeral Home chapel, 40-year-old Iris Martinez stood three feet from her father’s casket.

“Daddy!” she cried out, placing her hand over her Mickey Mouse mask.

Her best friend stood next to her, wrapping an arm around her for comfort.

In the casket, Rafael Martinez, who was 60 when he died, wore a Club America soccer jersey he received as a Christmas gift last year.

Her father’s death had been the nadir of a chain of hard months for Iris Martinez. She had lost her job as a paralegal in February. The following month, she contracted COVID-19. In June, her husband was laid off from his job at a cardboard box manufacturer.

During this brutal period, three of her relatives died of COVID-19 — in Maryland, Oregon and Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, her rent and bills — totaling $2,500 a month — piled up. Martinez had to dip into the savings account she had set up to help pay for her teenage daughter’s college education.

Her 19-year-old daughter has been working at Target and is helping the family with bills.

“That hit our hearts. It hurts that we have to put a stop to her dreams,” Martinez said. “I feel broken.”

Her father was not accustomed to not providing for his family. He had come from El Salvador to escape the civil war in his country during the 1980s. He worked as a mechanic at a body shop until he was able to get green cards for his family. Eventually, he worked and saved to own a body shop in Long Beach, but lost the business when his diabetes worsened. Late last year, his feet were amputated.

Then last month he found himself at the hospital, coughing and struggling to breathe. On the phone he told his daughter he was going to get tested for COVID-19.

“He said: I love you and take care and take care of your mom,” Iris Martinez said. “Those were the last words. I was lucky enough to talk to him before he died.”

On July 21, after being hooked up to a breathing machine, Rafael Martinez died as a result of complications from diabetes. The test results showed he was not infected with COVID-19. But whether he died as a result of the virus or not — in death it did not matter. His death unleashed the same chain reaction of heartaches and complications that many families are struggling with.

“Sometimes I feel depressed because I’m like: what’s going on?” Iris Martinez said. “Why is all this happening? What’s happening to us? Why did this happen to us?“

She turned to friends and family to raise money to cremate her father. She said the average cost was somewhere between $7,000 to $9,000. Then she came across Continental Funeral Home, which offered to cremate the body for $3,500.

Martinez said some funerals needed payment within 72 hours, but Continental gave her two weeks to come up with the money. She said she raised about $6,000.

“The whole process has been devastating for me and my family,” she said. “I feel that for us to heal, it’s going to be longer with all this going on.”

It was around 5 p.m. on Aug. 5 when the Juarez family began making its way into the parking lot. The family members sat in chairs, wearing masks; some wore latex gloves. A small table was set up for refreshments.

The casket sat open with a basket of red roses and sunflowers. A small red ribbon read in Spanish: My beloved husband.

The most Rev. Angel Velandia led everyone in a prayer before beginning his sermon. He had just been with the family members a week ago when they held a funeral service for Felipe’s brother, 55-year-old Medardo Juarez. Now, he told the mourners, for the first time in his 17 years in Los Angeles, he was holding a Mass for a funeral service outdoors.

“There are certain things in life we can’t make sense of,” he said. “Even if we could make sense of things, we will never get back our brother, Felipe.”

By the end of the service, some family members dropped their guard against the virus that had taken so much from them.

They hugged and stood near each other as they viewed the body that lay under an acrylic partition designed to protect them against an infection that could take even more.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.