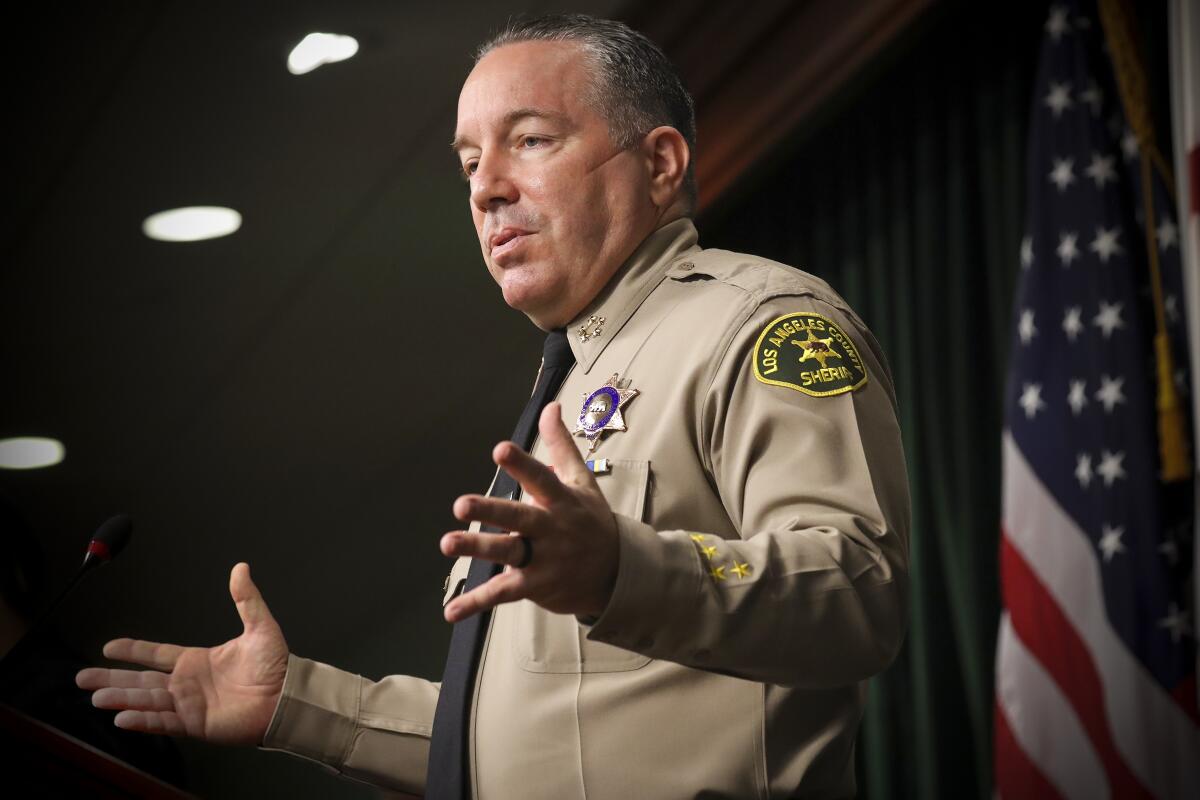

Sheriff Villanueva to fire or suspend 26 people involved in off-duty Banditos fight

Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva has moved to discipline 26 employees for misconduct related to a fight during an off-duty East L.A. station party at which several deputies said they were attacked by tattooed members of the Banditos clique.

Villanueva would not say how many of those employees he was seeking to fire, but a source with knowledge of the investigation said three deputies — Rafael Munoz, Gregory Rodriguez and David Silverio — face termination.

Cmdr. April Tardy said the policy violations included a failure to report the September 2018 incident to supervisors, as well as violations of policies that govern general behavior and conduct toward others.

The administrative investigation, which involved interviews with more than 70 people, found that some employees at East L.A. station were acting as so-called “shot callers,” controlling scheduling and events at the station, she said, using a term often used to describe top leaders in prisons and gangs.

An attorney for Munoz, Rodriguez and Silverio could not immediately be reached for comment.

Villanueva said the Sheriff’s Department will begin asking deputies accused of misconduct about their membership in deputy cliques such as the Banditos, which have plagued the agency for decades. He has said he also put measures in place in February that prohibit deputies from participating in illicit cliques.

“I’m adopting a zero-tolerance policy,” Villanueva told reporters Thursday. “If you form a group, you mistreat people, yes, we will seek to make sure you’re no longer a member of the department.”

He added later: “But we’re not gonna go on an inquisition and go through the entire 18,000 employees of the department to see if they have a tattoo or they’re a member of a group. That would be inappropriate and wildly speculative. We’re trying to run an organization, not engage in a witch hunt.”

County Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district includes East L.A., said in a statement that Villanueva’s action is “long overdue.”

“These are matters that need to be swiftly addressed to prevent more harm. The more we learn about deputy secret cliques, the more we deserve greater transparency and accountability of wayward deputies who disregard their colleagues and those they were sworn to serve and protect,” she said. “Implementing a zero-tolerance policy is one important step, but ensuring that the policy is instituted and practiced is key.”

Ron Hernandez, president of the Assn. for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, said “ALADS does not condone unprofessional conduct by deputy sheriffs, on or off duty. That said, we support a fair and deliberate process of accountability.”

He said the union encouraged members to participate in an ongoing study of deputy cliques by the nonprofit research group Rand Corp., which is scheduled to be completed next year.

Defenders of the deputy groups have said they represent not rogue cliques but camaraderie and a fellowship of hard workers. And sheriff’s officials have previously argued that deputies have an individual right to freedom of expression and association.

Observers called the move to ask accused deputies about their clique membership potentially groundbreaking if carried through.

“If they really do that in all discipline cases going forward that will be historic,” said Inspector General Max Huntsman. “I’ll believe it when I see it.”

Vincent Miller, who represents eight deputies, including those who said they were attacked at Kennedy Hall, said Villanueva’s announcement was hollow and intended to give the appearance that he’s tackling the problem when he is really serving as an “advocate for the gangs” while hiding behind the 1st Amendment.

“It’s way too late, way too little. And it doesn’t tell us anything about the systemwide deputy gang problem,” Miller said. He said his clients found “rat” scribbled on their cars and lockers. Two of them, he said, found a dead rat outside their homes — including one just a few days ago. All eight had to transfer out of the East L.A. station because of the hostility, he said.

The discipline comes after the L.A. County district attorney’s office in February declined to file charges against a sergeant and three deputies involved in the incident at Kennedy Hall, saying there was “insufficient evidence” that Sgt. Michael Hernandez as well as Munoz, Rodriguez and Silverio committed battery or any crimes. In a 28-page memo, prosecutors said 21 deputies identified as possible witnesses declined to be interviewed.

Because they weren’t compelled to provide statements, Huntsman has said the criminal investigation amounted to a cover-up.

“So as a result, a criminal prosecution was avoided — one in which the facts and details of the Banditos might have come into public light,” Huntsman said recently.

Villanueva’s move follows recent allegations from a whistleblower deputy that a gang of deputies who call themselves the Executioners dominate the Compton sheriff’s station. Chief Matt Burson said Thursday that the groups have caused “great embarrassment and concern” to the department and the community. He said the department’s Internal Affairs Bureau has launched a probe into the existence of the Executioners, but that “our intent is to examine the department in its entirety.”

“I am absolutely sickened by the mere allegation of any deputy hiding behind a badge to hurt anyone,” said Burson, who is in charge of professional standards.

Recent claims and lawsuits have underscored that elected sheriffs have failed for decades to root out the problem of tattooed deputy subgroups operating out of several Sheriff’s Department stations and using what critics allege are violent, intimidating tactics in communities. And it’s been costly.

Los Angeles County has paid out roughly $55 million in settlements in dozens of cases where sheriff’s deputies are accused of belonging to cliques. Those cases involve incidents that date to the early 1990s, when what a federal judge described as a “neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang” called the Vikings operated within Lynwood station. Other payouts involve the 3000 Boys and the 2000 Boys, involved in beatings at Men’s Central Jail.

Last year, the county settled for $7 million a lawsuit brought by the family of a 31-year-old man who was shot and killed by deputies during a foot chase in 2016. Deputies claimed the man, Donta Taylor, had a handgun, but no weapon was found.

Samuel Aldama, one of two deputies who shot at Taylor, admitted under oath to having a tattoo on his calf depicting a skull with a rifle and a military-style helmet emerging from flames. Aldama said he knew of other deputies at the Compton station with the tattoo, but he denied that the image represented membership in a club.

Aldama’s captain at the time said under oath in 2018 that he didn’t try to identify which deputies had tattoos out of respect for their 1st Amendment rights and the privileges granted to them by the Peace Officer Bill of Rights.

According to the attorney for the Compton whistleblower, the image on Aldama’s calf was found on a mouse pad and pencil holder at the station desk of an alleged member of the Executioners.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.