As COVID-19 cases surge, patients are dying at a lower rate. Here’s why

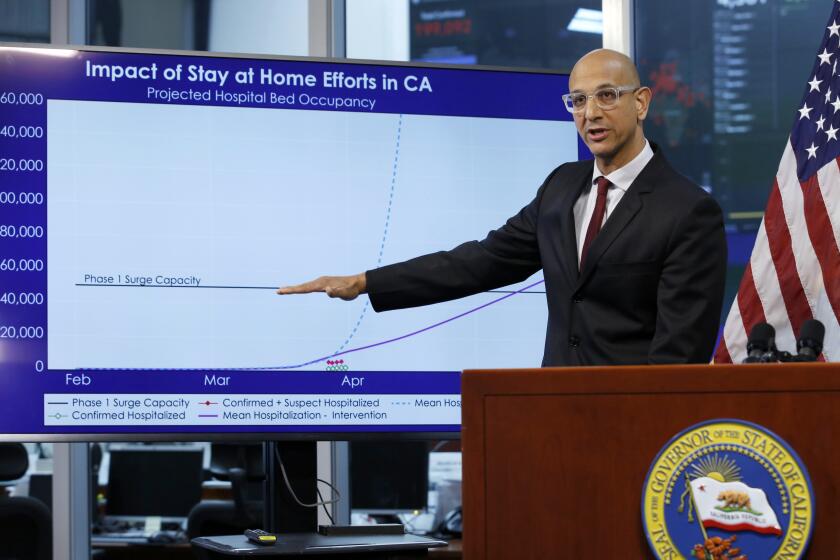

When the number of people being sent to the hospital with COVID-19 began to creep up in Los Angeles County early this summer, officials warned that a major increase in deaths was inevitable. A record-breaking number of cases could result in a record-breaking number of deaths, they predicted.

But nearly two months later, that has not materialized. The coronavirus continues to kill hundreds of people every week in L.A. County, but the death toll has remained lower than expected.

The trend is due in part to younger people falling sick, as well as better control over the disease’s spread in high-risk settings, such as nursing homes. But doctors say there’s another factor pushing up survival rates: better treatments.

“It was so grim in the beginning,” said Dr. Armand Dorian, an ER physician and chief medical officer for Verdugo Hills Hospital at USC. “Now we actually have regimens of treatments that do help. ... Since the beginning, say, February to now, we’ve learned a lot.”

The trends are not limited to L.A. County. In California, 3.6% of people diagnosed with COVID-19 between March and May died of the disease. Among those diagnosed between June 1 and Aug. 3, that figure dropped to 1.2%, according to a Times analysis of state data. Expanded testing, changing patient demographics and better patient care all played a role in that drop, experts say.

The statistic is what epidemiologists call the case-fatality rate: the number of deaths divided by the number of cases. This measures how deadly the disease is once people catch it — the chance of surviving. While the pandemic remains bleak, the lowered case-fatality rate is a glimmer of progress, experts say.

The case-fatality rate exists alongside another statistic: the mortality rate — deaths divided by the total population — which reflects the spread of the disease within the population.

In an interview with Axios released last week, President Trump discounted the nation’s mortality rate, which is worse than most other countries’, while lauding its case-fatality rate, which is better than most countries’.

But an improved case-fatality rate cannot offset the vast spread of the deadly virus, experts say. California’s mortality rate is rising as the state’s death toll from COVID-19 surpassed 10,000 on Thursday. If many people keep falling ill, then many people will die, even with improvements in survival rates.

A series of government data failures has created a backlog of as many as 300,000 test results in California.

Dr. Tim Brewer, an infectious disease specialist and epidemiologist at UCLA, said that even the medical improvements could be negated if the number of patients continues to grow. An overwhelmed healthcare system could hamper physicians’ ability to provide lifesaving care, he said.

“We’ve acquired a tremendous amount of information in the last seven months that has been helpful. We just need everybody to recognize that the virus has not gone away,” Brewer said.

When COVID-19 patients first began showing up in hospitals in the spring, doctors didn’t know which medicines or treatments would be effective. Little was understood about how the virus was transmitted or the best way to protect staff. USC’s Dorian described healthcare workers dealing with that unprecedented crisis as “deer in headlights.”

But that has changed rapidly as doctors around the world study and treat the coronavirus. Research findings in one country may within days become clinical guidelines in another.

“The collaboration between physicians all over the world over how to best treat COVID-19 has been quite extraordinary,” said Dr. Bilal Naseer, a critical care doctor in Sacramento with CommonSpirit Health, a large nonprofit hospital system. “I think the confidence level of physicians and healthcare teams is very high now — how to early-identify patients with COVID-19 and how to prevent severe disease is really much better understood.”

Early in the outbreak, panicked healthcare workers administered multiple drugs to patients to try to save them, unsure which may help. But that strategy made it hard to tell what was and wasn’t working, so physicians couldn’t gain knowledge they could use to help the next patients.

“Physicians around the world and in L.A. were basically throwing anything we could at these patients,” Brewer said. “We needed to get our panic level down a little bit and do research and trials and studies.”

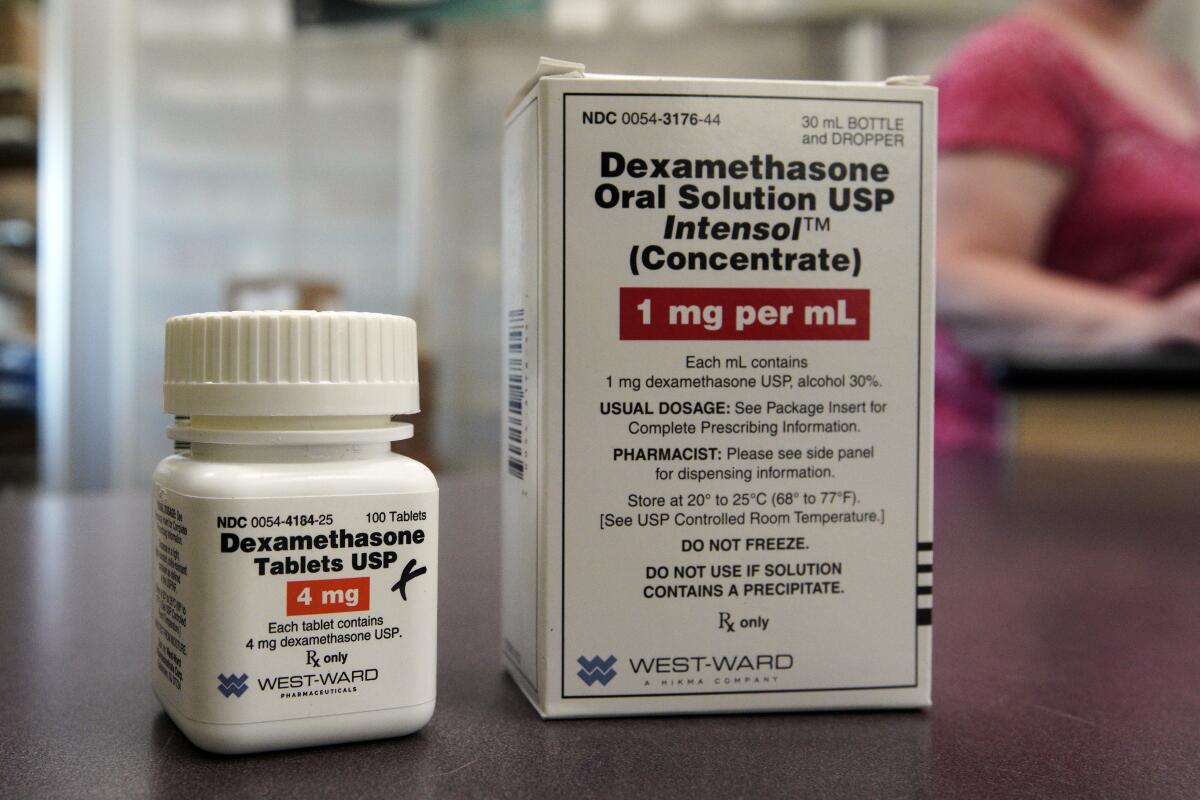

One of those studies, conducted by British scientists, led to a surprising finding. For other deadly coronaviruses, such as SARS and MERS, steroid medications had been shown to worsen symptoms.

But the UK researchers found that dexamethasone, a common and low-cost steroid, reduced mortality for patients on ventilators by a third, and by a fifth for those requiring oxygen, according to the study published in June.

Doctors had already begun administering remdesivir, an antiviral medication developed by Gilead Sciences, that had been shown to shorten the time it takes for patients to recover from the infection. Both medicines are now regularly prescribed by physicians treating COVID-19 patients, they say.

“We’re miles away from having real cures like vaccinations and more specific meds,” Dorian said. “But we have something. It feels good to say, ‘Why don’t we give remdesivir?’”

San Diego State University epidemiologist Eyal Oren pointed out that many people who get sick may not die, but will still endure long-term health consequences. He warned that looking at small improvements in survival rates may belie the reality that thousands continue to die from COVID-19, particularly people of color.

“Why do we have this many cases and this many deaths?” he said. “What’s the big picture?”

But for some, the improved survival rates are a sliver of hope.

Before the latest wave of patients in L.A. County, the most people ever hospitalized with COVID-19 in the county at one time was just over 1,950 in late April. That record was broken in July, when more than 2,200 people were hospitalized with the infection.

Yet, average deaths never exceeded what they had reached in the spring. The county’s case-fatality rate from COVID-19 has dropped from 4% in May to 2% now, according to county data.

“To me, that probably means we’re doing better care,” said Dr. Jeffrey Gunzenhauser with the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

Gunzenhauser said that the decline is probably also due to changes in who is falling ill. Infections have fallen in nursing homes, whose residents are particularly vulnerable to the virus, while cases have increased among young people, who are healthier and more likely to survive, he said.

When patients do end up in the hospital, doctors have new protocols to improve their odds of survival. Early in the pandemic, doctors rushed to put patients on ventilators when they were struggling to breathe.

But now it has become clear that it may not be necessary to intubate these patients, which can open them up to other complications that actually decrease their chance of survival.

Now, physicians lay patients on their stomachs to allow more oxygen into their lungs and give them oxygen through tubes inserted into their nose. Patients are put on ventilators as a last resort, doctors say.

“We were on a hair trigger to put people on vents at the beginning of the epidemic,” said Bradley Pollock, the chair of the department of public health sciences at UC Davis. “If someone looked like they were declining, we’re going to immediately put them on a vent — that was a mistake, in retrospect.”

How to protect yourself when caring for someone with COVID-19 at home? It can be done, by taking some basic and common sense precautions.

Doctors have also learned that COVID-19 tends to thicken patients’ blood and form blood clots, which can cause strokes and heart attacks. In some U.S. hospitals, clots were once reported to be the cause of 40% of COVID deaths. Now doctors know to administer anti-coagulants to prevent these deaths.

The knowledge gained over the last several months has improved care simply by making staff more confident, Dorian said. Patients benefit when healthcare workers aren’t stressed and can take their time with them and listen to their needs, he said.

“That’s what turns people around. It’s not just medicine, really,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.