‘I was naive to think this couldn’t touch my family’: Pacific Islanders hit hard by the coronavirus

It was still early in California’s coronavirus outbreak when Lina Ili started feeling the symptoms that would soon turn her family’s life upside down.

Coughing and running a fever, she holed up inside the bedroom of her Long Beach home for weeks. But breathing grew increasingly difficult, Ili, 46, said. “You couldn’t even lie down because it felt like a heaviness on your chest.”

On April 5, her husband, Aoga Ili Jr., decided it was time to take her to a hospital, where she tested positive for COVID-19.

The next day, her 22-year-old son, Taylor, was hospitalized. A few days later, her husband was too. In a matter of days, three of the five members of their household were put in the intensive care unit. Lina had it worst and spent four days on a ventilator.

“I wouldn’t wish it upon my worst enemy,” she said. “Just as simple a thing as to breathe, I don’t take it for granted anymore.”

The Ilis, whose parents came from Samoa more than 40 years ago, are among nearly 1,400 Californians with ancestry in Hawaii, Samoa, Fiji, Tonga and other Pacific islands who have been infected with the coronavirus, which is sickening and killing members of the small but close-knit community in disproportionate numbers.

In L.A. County, Pacific Islanders suffer the highest infection rate of any racial or ethnic group, more than 2,500 per 100,000 residents. That’s six times higher than for white people, five times higher than for Black people and three times higher than for Latinos, according to county health demographic data that exclude Long Beach and Pasadena, which have their own health departments.

Health experts say the reasons are similar to why Black people and Latinos are falling ill and dying at higher rates: reduced access to healthcare; higher levels of poverty; crowded housing; multigenerational households that make it more difficult to physically distance or quarantine; and higher rates of underlying health conditions that increase risk for severe illness from COVID-19, such as heart and lung disease, asthma and diabetes. Many Pacific Islanders also work in front-line jobs, such as food service, hospitality and healthcare, at which they are more likely to contract the virus and bring it home.

But community leaders say there are other factors that are unique to the culture of Pacific Islanders, and they say that public health officials have failed to adequately address them.

Among these factors are cultural traditions that center on large family gatherings, in-person church services, funerals and birthday celebrations that, in some cases, have continued despite orders to maintain social distance. Leaders in the Pacific Islander community say also that a cultural stigma associated with a positive diagnosis may be facilitating the spread of the virus.

“The shame factor of it is real,” said Dr. Raynald Samoa, an endocrinologist at City of Hope in Duarte who battled COVID-19 himself. “People are not getting their families tested. They’re not speaking out, they’re not getting identified because they’re afraid that they’re going to have to stay home from work or that it’s going to negatively impact their family.”

Samoa has helped raise awareness by speaking about his experience in Facebook videos and other appearances and urging Pacific Islanders to take the virus seriously and heed health guidelines.

Samoa faulted health officials for taking no proactive measures to reduce rates of transmission and infection in Pacific Islander communities.

“I wish there were things in place, but there was nothing,” Samoa said. That left it to Pacific Islander groups to assemble their own COVID-19 response team, devise their own strategy and messaging based on past work with chronic diseases such as diabetes and cancer, and push the county to use it.

California is home to nearly 317,000 Pacific Islanders, and more than 55,000 of them reside in Los Angeles County, according to census data that include people who identify as multiracial, which is common in the community.

Statewide, Pacific Islanders have experienced infections and deaths at higher rates than most other groups, but the disparities aren’t as pronounced as they are in L.A. County. Their statewide infection rate is three times higher than that of white Californians, and 20% higher than Latinos’ infection rate, while their death rate is nearly 60% higher than that of white people but lower than that of Black residents.

Although numbers remain small overall — California has reported 35 deaths and 1,389 confirmed cases among Pacific Islanders as of July 15 — they reveal an outsize toll on a community that already experiences higher rates of underlying health conditions. Sixteen Pacific Islander residents in L.A. County have died, for a rate of 83 per 100,000 people — twice as high as white and Latino county residents.

Health officials say they are not surprised by the high rates of illness.

“Sadly, these disparities are consistent with other health disparities we see and reflect deeply rooted and pervasive inequities in our society that are in part fueled by racism, xenophobia, and a lack of opportunities and resources to support optimal health,” Natalie Jimenez, a spokeswoman for the L.A. County Department of Public Health, said in an email.

The county health department has examined statistics on Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders “from the beginning of the COVID epidemic” but did not initially report them to protect confidentiality “due to the low numbers of reported cases and deaths,” Jimenez said.

Local health officials began releasing data on infections and deaths among Pacific Islanders at the urging of community groups that saw a lack of targeted response. Pacific Islander leaders began pushing officials, county by county, to release data on their community rather than lump them together with Asians.

In L.A. County, health officials began publishing those numbers in late April, two days after Pacific Islander groups requested them in a Zoom meeting.

Jimenez said that “the reason we began publishing the disaggregated data was that, based on the community’s input and the unprecedented threat posed by the COVID epidemic, we felt that the benefits outweighed the risks of posting the statistics.”

Those statistics have been crucial for getting people in the community to take the threat seriously, said ‘Alisi Tulua, a program manager with the Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance, which pushed for their release. “We’ve been using the data as our biggest, most convincing talking point.”

With the partial reopening and recent surge in cases, however, community groups and faith leaders fear they’ll only see the trend compounded as waves of the virus spread through their families and churches.

“Our community is back to work and more exposed. So it’s going to be twice as hard to quarantine and try to get tested,” Tulua said. “While it’s flattening for other people, it’s still climbing in our community. If we bring it home, maybe we’re OK, but our parents will suffer. And if we’re not careful, we’re going to kill off a whole generation of our people.”

Jimenez said the L.A. County health department has been working with Pacific Islander groups for a few months to create “culturally relevant and sensitive materials” that resonate with the community. That includes “tailored outreach” with educational graphics that will be shared on social media in the Tongan, Samoan, Chamorro and Marshallese languages, public service announcement videos featuring Tongan, Samoan and Chamorro community leaders and photos of Pacific Islander families wearing masks. Those materials are being distributed to community leaders, she said.

Because health officials had not yet released data on Pacific Islanders, the Ilis didn’t know their community was seeing higher rates of coronavirus infection when they started getting sick.

The oldest son, Pele Ili, 26, quickly became the only healthy adult in his household, and suddenly found himself the caretaker for his whole family, tending to his sick parents and brother while trying to protect his 12-year-old brother, Solo, from falling ill too.

On Easter Sunday, Pele, a service manager at a payroll company who also blogs, posted about his family’s experience on Instagram in an effort to get others to take the stay-at-home orders seriously.

“I was naive to think this couldn’t touch my family. I was ignorant to think that me feeling healthy meant that I was okay to attend a few small gatherings but little did I know my house was compromised,” Pele wrote on April 12. “... This could happen anywhere, anytime, and to anyone whenever you’re not home. No one is above this.”

Being outspoken was important to combat the stigma, Pele later said. “Pacific Islanders have this sense of pride, where they can take care of themselves and they want to keep everything in house, you know, just to not draw as much attention on our family.”

He documented his family’s ordeal, shooting extensive video and posting it on YouTube, and now looks back on it as one of the most overwhelming and emotional times of his life.

“There were times where I didn’t know if they were ever gonna come back out,” he said. “They could barely talk. And I think the hardest part was just not knowing what was going to happen.”

Dr. Samoa and other leaders worry that, in addition to being exposed to the virus at the workplace, people are being exposed to COVID-19 at churches that are the heart of many Pacific Islander communities.

Although some have taken health precautions, others have seemingly ignored them, including one church that held an in-person fundraiser last month that was also streamed online, Samoa said. “I didn’t see a mask in that place, and the social distancing was minimal.

“Churches are where people congregate; it’s the village center,” Samoa said. “So if the village leadership is not promoting safe behaviors, then the community suffers.”

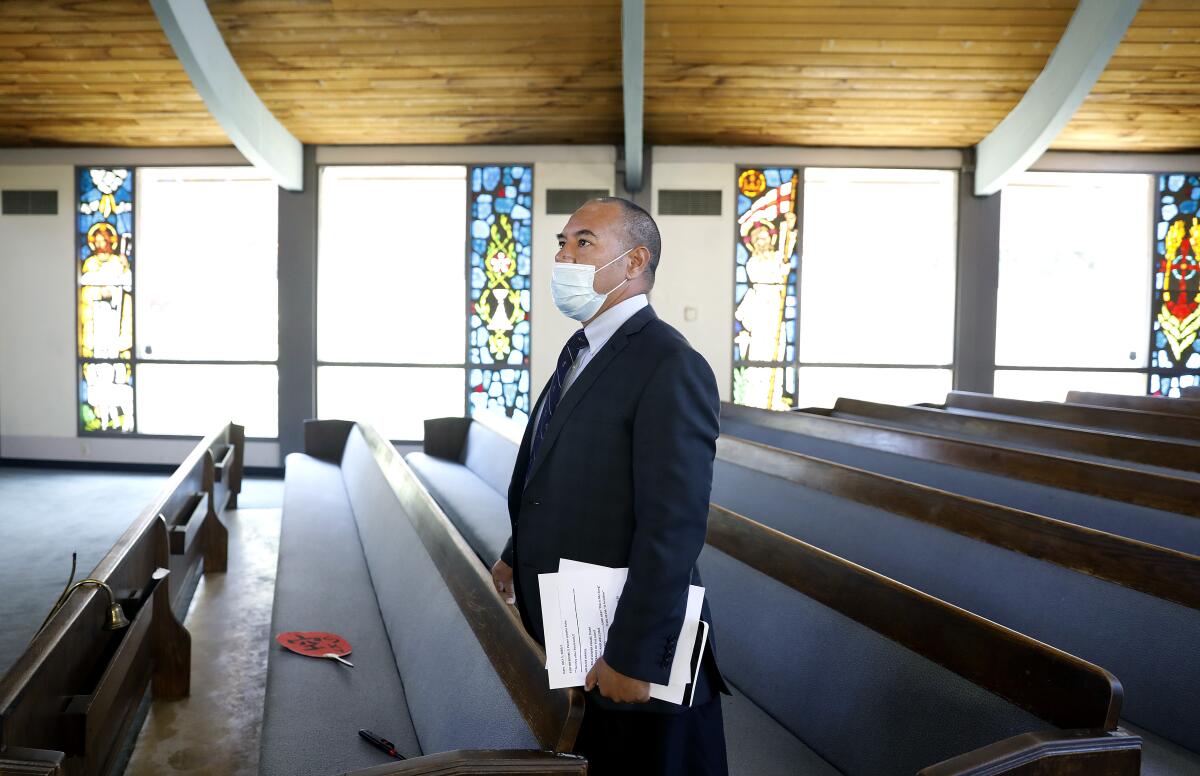

The Rev. Kitione Tuitupou, pastor of First United Methodist Church of Bellflower, a multiethnic congregation of about 100 people that is majority Tongan, has been playing it safe, livestreaming Sunday services since stay-at-home orders were issued in March.

Although people are eager to return, they are also fearful, he said. “People’s faith really holds them up at this time. So even though they really want to come back to church, we remind them to be patient.”

For the Ilis, the sudden suspension of in-person gatherings has been difficult and isolating.

They had to halt their weekly attendance at St. Cornelius Church and the meals they shared with extended family afterward in favor of a livestreamed Mass. Yet they’ve adopted new traditions to stay connected, like a 5:30 p.m. Zoom prayer hour with out-of-state family members.

“We’re learning to be creative,” Pele said.

Lina Ili, now recovered, to this day doesn’t know where she contracted the virus but is still dealing with the stigma.

“People are still kind of afraid to be in the same area as us,” she said. But, at this point, she said she only regretted trying to fight off the illness at home for too long.

She, like her oldest son, now speaks at webinars urging other Pacific Islanders who may be feeling symptoms to get tested and seek medical help.

“The hardest part for our culture is admitting you need help,” Lina said. “You could be helping someone else, or saving a life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.