When a Qatari sheikh came to live in L.A., an entire economy sprouted to meet his wishes. “His highness doesn’t like to hear no,” one associate told a professor.

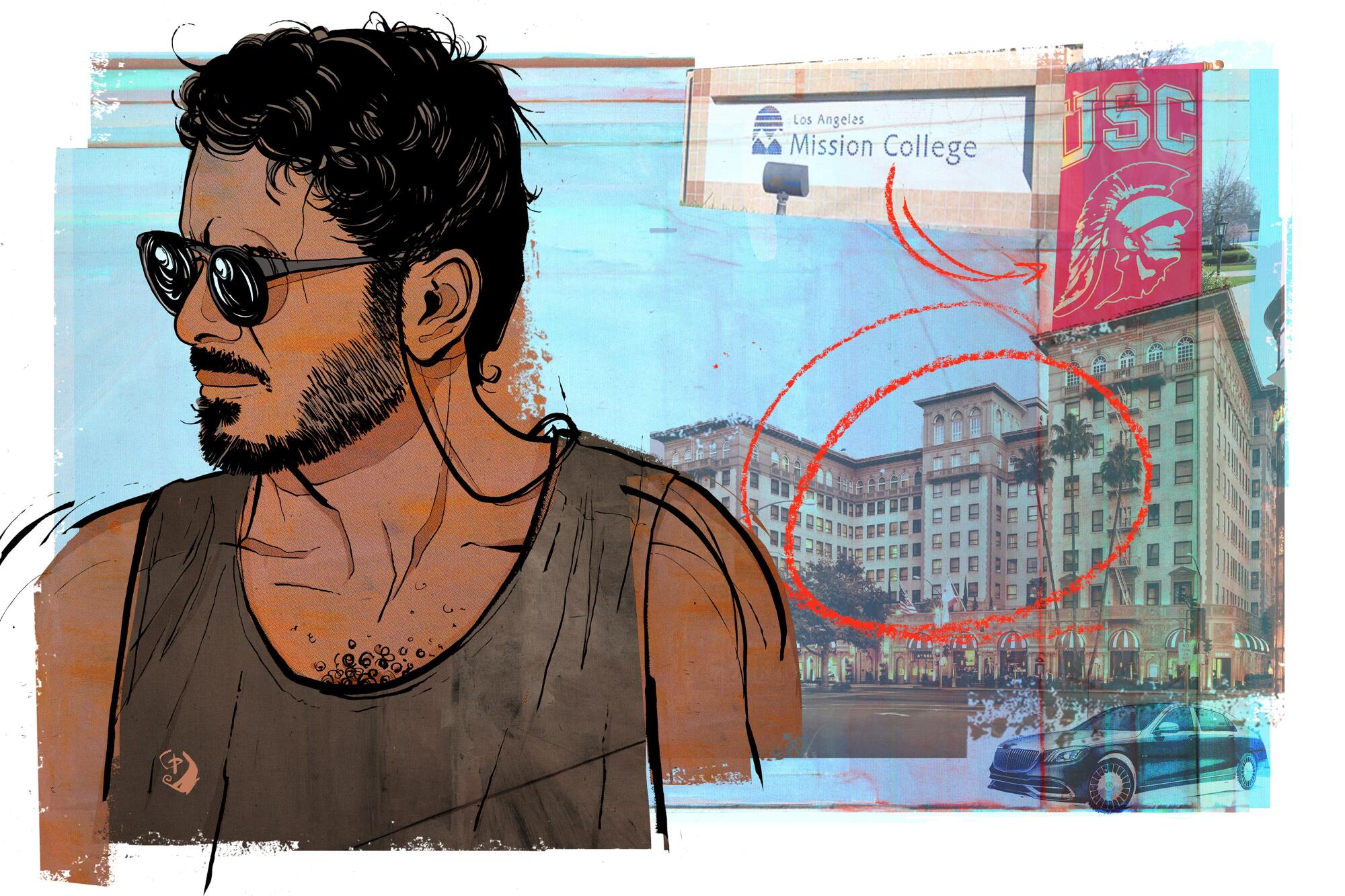

Los Angeles has long enjoyed a reputation as a playground for the rich, but the handsome teenage prince who arrived nine years ago operated on a different level.

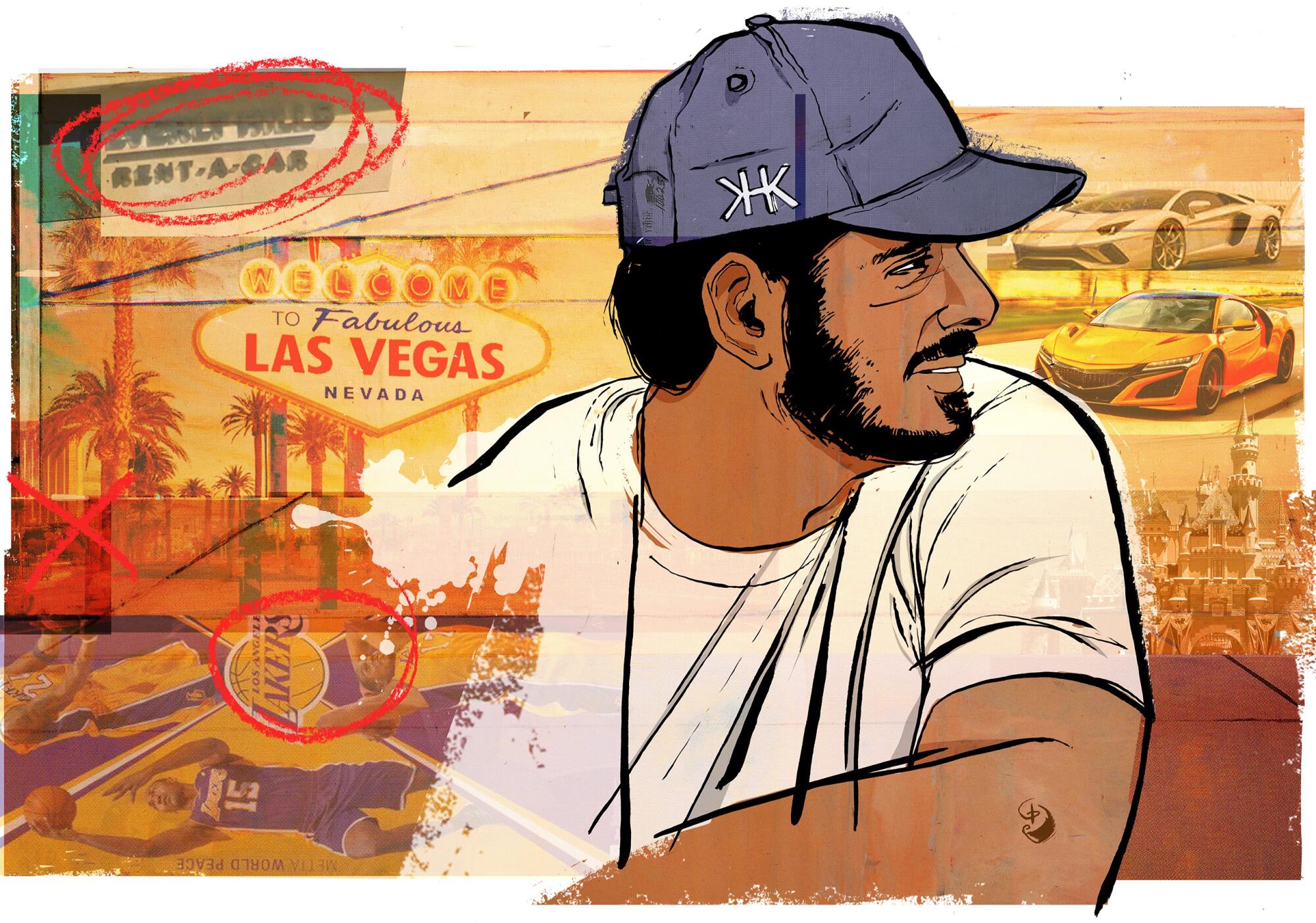

He came from the Persian Gulf nation of Qatar on a private jet with a squad of servants, a bottomless natural gas fortune and the stated goal of a college education. He installed himself in the Beverly Wilshire, the hotel that “Pretty Woman” made famous, and embarked on a lifestyle that few undergraduates could imagine — luxury suites for Lakers games, lunch at the Ivy and regular excursions to gamble in Las Vegas.

He took the town with an entourage, a rotating collection of cousins and friends from back home, in a fleet of exotic sports cars, rubbing elbows with a flashy set that included Scott Disick of “Keeping Up With the Kardashians,” and announcing his exuberance in custom trucker hats emblazoned with his initials: KHK.

Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the son and, later, brother of Qatar’s emir, eventually graduated from the University of Southern California and returned to the Middle East. He became an officer in the country’s internal security service and has cultivated an image as a jet-setting heartthrob. His Instagram account, with more than a million followers, has featured the dashing, goateed royal yachting, driving priceless autos, skydiving, and occasionally cuddling with baby tigers.

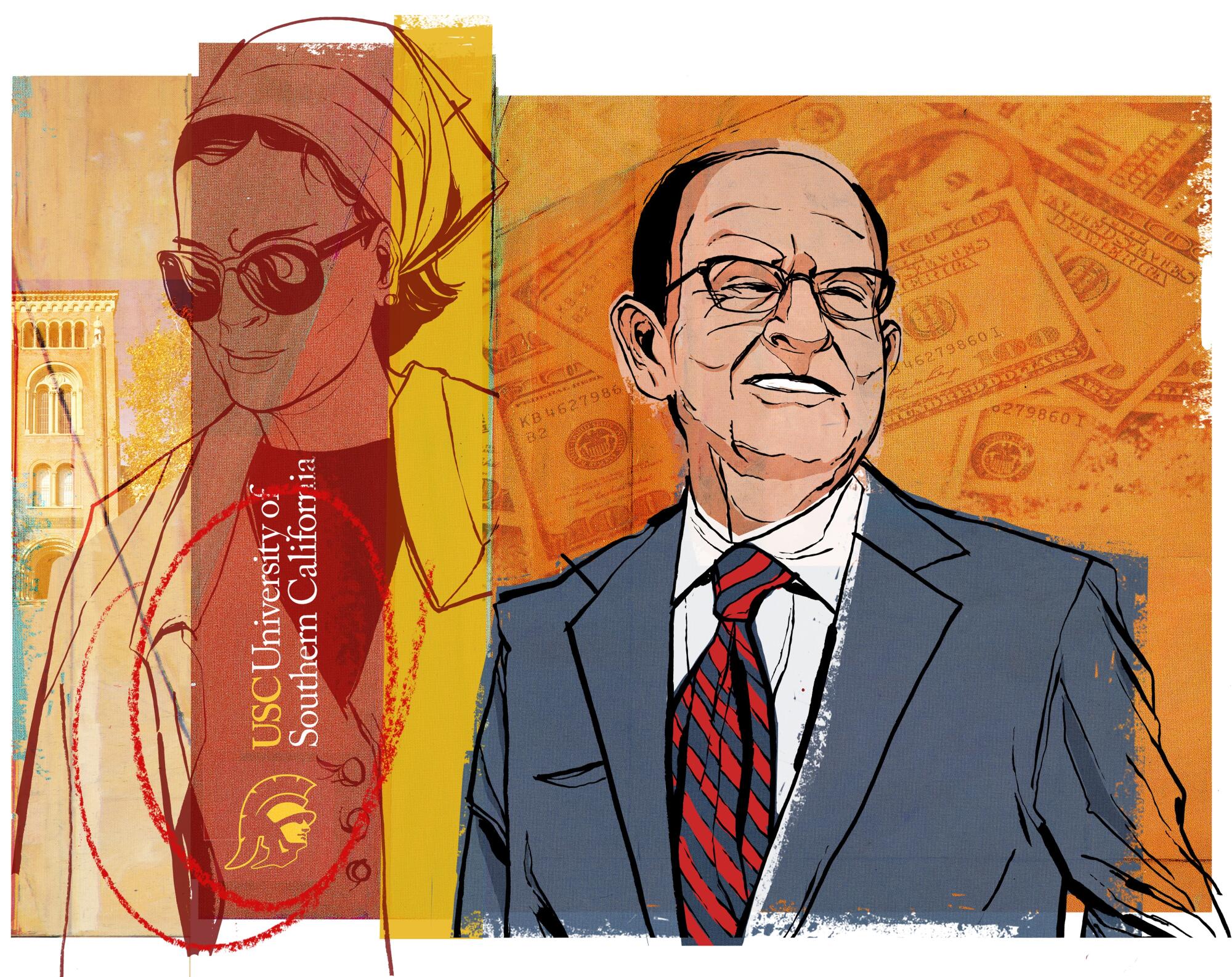

His college years in L.A. were a closed chapter in a colorful life, and they probably would have stayed that way were it not for a series of indictments last year by federal prosecutors in Boston. The charges in the college admissions scandal did not involve Al Thani or his family, but the high-profile prosecution, with its allegations of wealthy parents scheming to get underqualified offspring into USC and other universities prompted some who knew the prince to reconsider the circumstances of his education. Shortly thereafter, The Times received a tip to look into his college degree.

From the moment Al Thani stepped off the plane, an entire economy quickly grew up around him to meet his wishes and whims: chauffeurs, a security detail, concierges, trainers, a nurse, an all-purpose fixer and even, according to several USC faculty members, a graduate student who served as his academic “sherpa.”

Before he started classes, a billionaire trustee arranged a private meeting between the university president and the prince’s mother, and once he arrived, the institution showered him with special treatment.

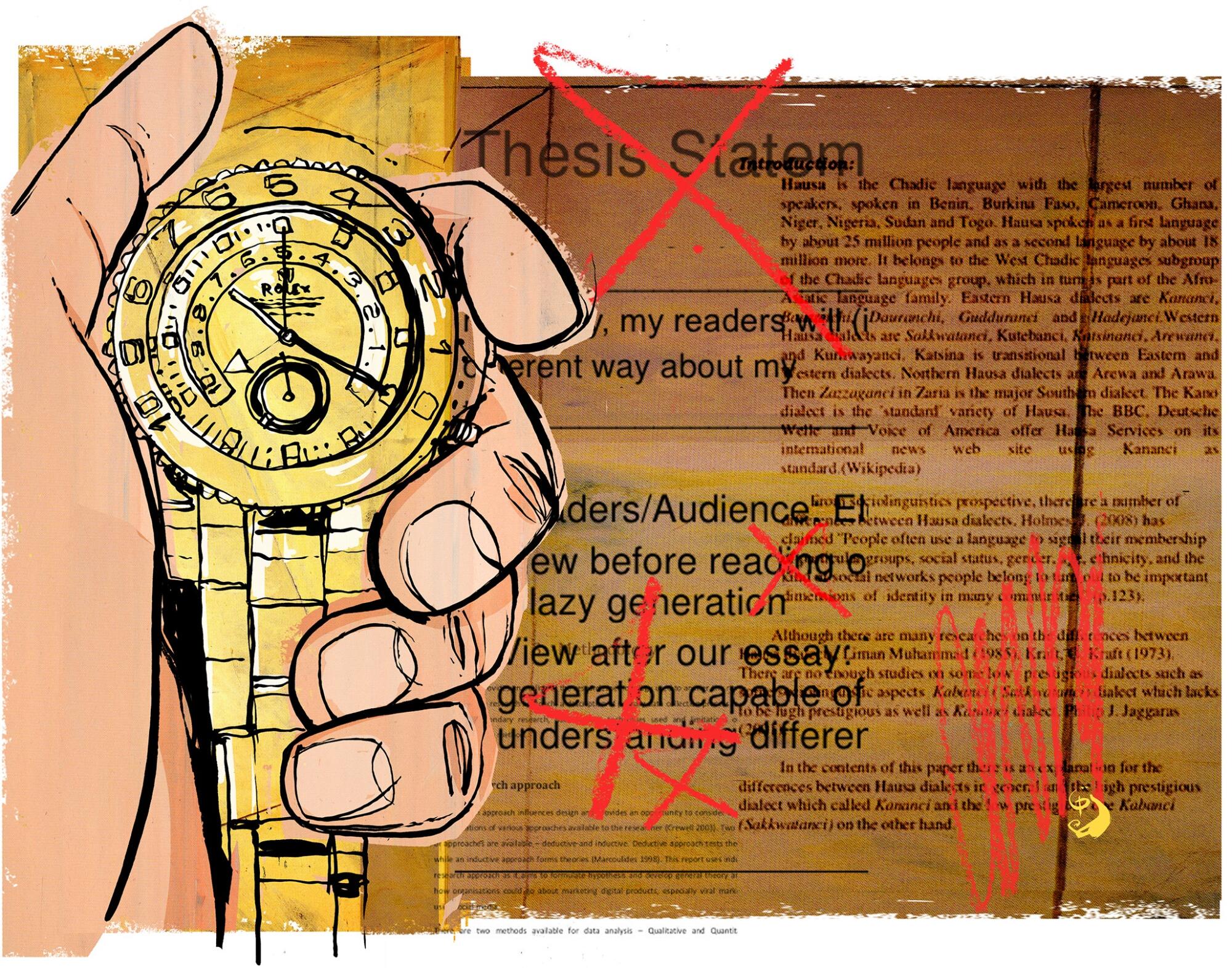

He was allowed to blow off class for dubious “security reasons” as an undergrad, then was handed a master’s degree for a period in which he took several vacations in Europe and never stepped foot on campus.

His enablers went to extraordinary lengths to keep him happy: Forging documents, flouting university rules, plying a UCLA dean with a golden camel statue, giving a Rolex to a professor and even, accounting records and interviews indicate, buying a $500 gift for a DMV employee in an effort to secure a coveted vanity plate.

The government of Qatar did not answer requests to interview the prince, now 28; his mother — an internationally renowned educational philanthropist; or others connected with his stay in L.A. A New York attorney representing the prince, David G. Keyko, did not answer dozens of questions submitted in writing. In a letter to The Times, he said, “Your research thus far has turned up suspicions, suppositions and multiple levels of hearsay about matters that, if they took place at all, happened years ago.”

This week, Max Shulklapper, a spokesman for the prince, said the questions The Times raised were racially insensitive, “if not outright bigoted”: “Would you be asking these questions if a white student allegedly did not show up to his college class, or was pulled over for speeding? Would you ask these questions if a white student’s parent allegedly donated money to a university toward its betterment?”

***

The prince was raised in a family that prized higher education. His mother, Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, is a world-renowned advocate for university learning who established an enormous college complex in Qatar. His father, Hamad, who served as emir until 2013, attended the British military academy Sandhurst, and his older siblings went to elite universities including Harvard, Duke and Georgetown.

The youngest boy in the family wanted something different — a college education in the sun-kissed city that has long been a vacation destination for Middle Easterners.

L.A. may have appealed to the prince’s laid-back style. While his mother dressed in couture and his father in tailored suits or the traditional Qatari thobe, he often wore backwards ball caps, beanies, athletic shorts and hoodies.

He began his academic sojourn in February 2011 in a place about as far from the palaces of his youth as one could imagine, L.A. Mission College.

A community college set among the tract homes of Sylmar, Mission has an overwhelmingly Latino and low-income student body. Nearly 60% of students are considered “food insecure,” and more than 1 in 10 are homeless.

Why the prince chose Mission is unclear. The campus was 25 miles from the Beverly Wilshire, where he lived, and the drive, largely along a notoriously clogged stretch of the 405, could take more than an hour one way. There were at least nine community colleges closer to the hotel, and they offered nearly the same courses.

Al Thani signed up for classes along with two cousins in his entourage, Nasser and Jabr. After the first day at Mission, the prince rarely attended class, said former chauffeur Martin Agabus and another employee who, like many of the prince’s ex-staffers, spoke on the condition of anonymity to preserve future job prospects.

International students were rare there — less than 2% held student visas — and Middle Easterners were particularly uncommon, the faculty and staff said. Yet faculty and staff contacted by The Times said they were unaware that Qatari royals were among them.

***

Even in Beverly Hills, where rich people with money to burn are about as common as valet stands and brow lifts, the prince’s wealth was notable.

Since the 19th century, his family has ruled the tiny nation of Qatar, one of the world’s richest countries on a per capita basis. It sits atop vast natural gas and oil reserves, generating billions in annual proceeds. With their fortune, the Al Thanis have purchased iconic hotels, a French soccer team, Miramax film studio, a Sardinian resort, thoroughbreds, yachts and masterpieces of art. In L.A., the family sank more than $300 million into constructing a Bel-Air hilltop compound anchored by a 77,000-square-foot mansion.

When the prince arrived in L.A., Qatar laid out for a small army of servants to attend to him, including one man who made his tea and another who prepared his hookah.

“We thought we were gods. We were making so much.”

— David Sajasi, Beverly Hills Rent-A-Car partner who oversaw the prince’s account

At the Beverly Wilshire, his butlers lived in $600-a-night rooms and the half-dozen chauffeurs and security guards dined in the hotel restaurant, where a cheeseburger ran $30. The prince and his friends stayed in suites with views of Rodeo Drive.

The task of paying the bills fell to an American who lingered on the edge of the prince’s entourage.

Joseph Jourieh, 60, had a number of official titles at Qatar’s U.N. Mission, including director of public relations and travel coordinator. A Twitter bio described him as a “solution finder.” His background also included a New York state charge in 2018 that he bribed a supervisor at JFK airport with limousine rides, meals and a watch so that Qatar could park its diplomatic airplanes overnight during the United Nations General Assembly, a violation of airport rules. The supervisor pleaded guilty last year to receiving unlawful gratuities and official misconduct; Jourieh contested the charge and prosecutors ultimately dropped the case against him.

When Al Thani moved into the Beverly Wilshire, Jourieh flew to L.A. and took up a role somewhere between fixer and babysitter. Among his responsibilities was to approve bills before they were sent on to the Qatari government, according to interviews with former staffers and invoices reviewed by The Times.

It was not always a straightforward process. The prince and his friends didn’t want people back home knowing all of their American exploits.

Jourieh struck up a relationship with Beverly Hills Rent-A-Car, a scrappy Westside outfit known for leasing exotic vehicles to tourists. The company started churning out bills to send to the Qatari government for all manner of needs: day use of a Maybach ($2,900), a security guard ($600), a pair of cook assistants ($475 each), VIP Disneyland tickets and tour ($9,600), a VIP package for the Clippers ($23,000) and a suite for 12 at the Lakers ($12,750).

The invoices ran for pages and pages, making it difficult for the Qatari government to detect improper charges or inflated costs, according to accounting logs and interviews with employees.

In one example, the car rental agency paid $200 for a Virgin Airlines flight and then charged the Qataris $8,700, according to company records. The company billed $73,000 for legal fees for a nonexistent attorney, company officials acknowledged to The Times. It’s unclear whether the prince himself knew the details of the billing.

In any case, the overcharges created a slush fund that was used in part to pay for whatever the prince wanted kept off the books, according to former Chief Financial Officer Mohamed Diakite and other employees familiar with the Qatari account.

Over six weeks in 2014, the car agency laid out $300,000 for the prince and his entourage to spend at the Wynn Resort and Casino during trips to Las Vegas, the records show. Although gambling is forbidden in Islam and treated as a crime in Qatar, Al Thani and his entourage frequently visited Las Vegas, according to social media posts and billing records reviewed by The Times. Former employees said they witnessed the men gambling on the casino floor.

The way Beverly Hills Rent-A-Car dealt with Qatari billing alarmed some at the company. In sworn testimony in a 2012 lawsuit against the company, a former financial executive termed the handling of Qatari cash “illegal.” A former company president alleged in a lawsuit last year that the company generated “fraudulent invoices ... to facilitate misappropriation of funds as well as to overcharge customers.”

Diakite, the former CFO, said that over his eight years of employment, he grew concerned he was participating in “flat-out fraud” by the company, one of numerous accusations he leveled in a lawsuit last year. He and the company are suing each other over the circumstances of his termination.

In an interview, the car rental partner who oversaw the prince’s account, David Sajasi, acknowledged that he concealed expenses that Al Thani and his entourage “didn’t want [their] parents to know” by listing them as “other bills” in the invoices.

“We thought we were gods. We were making so much,” Sajasi said.

After Al Thani returned to Qatar, the gush of money dried up, and the company went out of business.

In a brief phone call, Jourieh, the fixer, declined to answer questions, adding, “Whatever I’m going to say is not going to change anything.”

***

The longer the prince stayed in L.A., the more money the grande dame hotel at the corner of Wilshire and Rodeo took in.

One way to keep Al Thani and his entourage under the Beverly Wilshire’s roof was to make sure he remained a student.

When Al Thani was in his second year of community college, Chris Gleeson, a hotel executive in charge of international business, reached out to UCLA.

“I told them repeatedly that first of all, as a dean, I did not handle admissions at all; and that we cannot admit somebody because of some special status.”

— Alessandro Duranti, then-dean of social sciences

Gleeson told an administrator that the son of Qatar’s emir was interested in political science, and suggested that if UCLA played its cards right it could be in line for a substantial donation, according to an email the administrator wrote afterward.

It was not an altogether outlandish proposition. Under the leadership of the prince’s mother, Qatar has given more than $1 billion to American universities, making it the largest foreign funder of U.S. higher education.

Gleeson’s call led to a meeting with Alessandro Duranti, then dean of social sciences. The hotel executive, Jourieh and an associate arrived at his office with a set of golden camel statues and a few other gifts, and the delegation made it clear that they wanted a promise of admission for the prince.

“I told them repeatedly that first of all, as a dean, I did not handle admissions at all; and that we cannot admit somebody because of some special status,” Duranti said.

Al Thani’s representatives kept pushing for an hour, he recalled, with one telling him, “His Highness doesn’t like to hear ‘no.’” The dean refused to budge.

The Qataris shifted their attention from Westwood to USC.

The Al Thanis knew several USC trustees, including Thomas J. Barrack Jr., a wealthy L.A. investor and founder of Colony Capital Inc. who oversaw construction of the family’s Bel-Air compound. The fall after UCLA rejected the Qatari overtures, Al Thani’s mother, Sheikha Moza, came to L.A. and Barrack arranged a visit with USC’s president.

C.L. Max Nikias was then in the middle of a $6-billion fundraising campaign, one of the most ambitious capital drives ever in higher education, and both people in the room that day knew Qatar was in a position to give generously to USC.

Four months after the meeting ended, the prince started at USC as a transfer student. His cousin and close friend Nasser enrolled alongside him. Around the same time, USC began pursuing a significant grant from the Qatar Foundation for the university’s marine research center on Catalina Island.

USC referred questions about the meeting to Nikias, who resigned in 2018. In a statement, Nikias said that he “had no discussions about the possible admission of her son” during the meeting. Moza’s nonprofit, the Qatar Foundation, said in a statement that the prince had already been admitted, and described the meeting as “a courtesy visit.”

“At no time during the meeting were potential grants or other financial contributions discussed,” the foundation said.

Once classes began, Al Thani displayed little enthusiasm for his studies, according to people who worked for him. He spent much of the day in his suite at the hotel, playing video games with his entourage and working out with a trainer, former employees said. He passed many evenings chatting with friends at Urth Caffe. On infrequent and brief trips to campus, he liked to stroll the grounds and visit dining establishments, the employees said.

Yet he made the dean’s list three times.

One possible explanation for this academic success was his relationship with a grad student named Juvenal Cortes. Cortes was a teaching assistant in a political science lecture course Al Thani and his cousin enrolled in their first semester at USC.

It was an unlikely pairing. Cortes was a Mexican immigrant who grew up near the Port of L.A. in an apartment he shared with seven relatives. His rise from poverty to a doctoral program at USC’s political science department was a point of pride for him and the university. Eventually he would secure a position as an assistant professor at Occidental College.

“I don’t think he was fully aware of the American educational system.”

— USC adjunct professor

As a doctoral student, Cortes received free tuition and a stipend to cover living expenses, and was not supposed to work outside the university without permission.

But shortly after he met the Al Thanis, Cortes started telling others that he had a side gig with the prince. At a meeting with Steven Lamy, then a vice dean for USC’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Cortes explained that he was working for the royal “to make extra money.”

“He was acting as a sort of guide [or] sherpa for this emir’s son,” Lamy said.

Lamy, who had been at the college since 1982, said he had never heard of such an arrangement but he listened as Cortes sought his advice about how to ask faculty for special treatment for the prince.

“He said, ‘There are going to be times he’s going to be out of town,’” Lamy said. “I said, ‘Professors are sovereign. You have to work it out with them.’”

At mandatory meetings with his political science department advisor, the prince arrived with Cortes, and the grad student took an active role in mapping out Al Thani’s course schedule, advisor Paul Kovich recalled.

Cortes also approached professors on behalf of the prince and his cousin. One adjunct said Cortes introduced himself as the prince’s emissary during a 2013 course and encouraged the instructor to come to him with any problems, an offer the professor declined. Another untenured instructor said in an interview that Cortes took him aside at the beginning of a 2015 course and said Nasser Al Thani would never attend the class but should “do well” grade-wise. The request did not seem “on the up and up,” the professor admitted, but he complied nonetheless.

A Qatari government spokesman did not respond to questions about Nasser Al Thani or the untenured professor’s account.

In at least two other courses, Al Thani was excused from attendance after he invoked unspecified “security reasons” and got professors’ permission to submit work electronically.

Campus police were not informed of any threats related to Al Thani, and Lamy, the former vice dean, said he was normally told of legitimate safety concerns. “I would’ve had a briefing. I got no briefing,” he said.

How Cortes was compensated, and the scope of his duties, are not clear.

Eight people who worked at Beverly Hills Rent-A-Car said they were told by Sajasi, his assistant or others at the company that a person was being paid to do the prince’s schoolwork. None was informed of the person’s name.

Diakite, the former CFO, said Sajasi told him in a 2015 conversation that he should bill Qatar for the cost of a Mercedes SUV as a way to partially compensate the person. A March 2015 invoice shows the country was charged $118,000 for a Mercedes, and three other former employees confirmed Diakite’s account. There’s no indication Cortes or anyone else connected to Al Thani’s education ever received the vehicle and the records do not show where the money paid by Qatar for the Mercedes went.

Sajasi denied his former employees’ accounts and said his company did not compensate anyone in connection with the prince’s education. He added, “People that have worked in lower jobs make things up because they are juicy.”

Approached outside his Occidental office last year, Cortes said he did not know anything about a USC student aiding a Qatari prince.

“You should really talk to the [political science] department,” he said, before ending the conversation abruptly. He declined subsequent interview requests and refused to answer detailed questions submitted in writing.

The prince did show up to at least two classes at USC, one in international relations and one in political science, both taught by the same professor. The professor, who was familiar with Middle East politics, told Al Thani at the start of the first course that he knew who he was, and gave him and his classmates a warning: I take roll every class and attendance is mandatory.

Al Thani showed up to the class regularly and signed up for a second one taught by the same professor the following semester.

When the final paper was due, Al Thani asked for an extension and the adjunct granted it, as he said he often did for students. A chauffeur later delivered the paper in a bag that also contained a Rolex.

Stunned, the adjunct said he went to the Beverly Wilshire and returned the watch.

“I don’t think he was fully aware of the American educational system. I felt this was a chance to educate him. I said, ‘This is completely unacceptable,’” said the adjunct, who requested anonymity to speak candidly about a former student.

The next year, the same driver delivered the Rolex again; this time, the prince refused to take it back.

The adjunct researched selling the watch to benefit USC, but found that it was already registered in his name with Rolex. Instead, he wrote a check to the university for its estimated value, $12,500. USC confirmed his account.

The adjunct has never worn the watch, he said. It remains in a drawer in his home.

***

It was 1:20 a.m. on a school night in 2014, and Khalifa Al Thani was tearing down the 10 Freeway at 130 mph in a white Maybach. He and his entourage were returning from several days at the Wynn in Las Vegas, and the prince was driving so fast that a Range Rover driven by one of his chauffeurs could barely keep up.

The California Highway Patrol pursued the vehicles, and after they exited at La Cienega, officers detained the prince and his entourage and gave him a citation for speeding. L.A. prosecutors would later allege in a criminal complaint that he was driving recklessly and flaunting a dangerous speed.

Al Thani never showed up to his arraignment — even after prosecutors sent a notice to the Beverly Wilshire. There is still an active warrant for his arrest.

Fast cars were the prince’s great love. He rented some in California and brought two of his own: a $890,000 McLaren and a $1.5-million LaFerrari.

Those vehicles achieved their own kind of fame in West L.A.: Car enthusiasts shot videos of them parked outside the Beverly Wilshire, and Scott Disick, the ex-boyfriend of Kourtney Kardashian, posed on the hood of Al Thani’s McLaren. “Thanks for the ride @KHK,” Disick captioned the photo on Instagram, which was later published by the Daily Mail.

Al Thani wanted something more — a California license plate bearing his initials, KHK, according to two former employees. But there was a problem: The vanity plate was already registered to another motorist.

Sajasi’s assistant went to a Target near the Long Beach DMV in November 2014 and charged $524 on a Beverly Hills Rent-A-Car credit card.

“Gift for DMV rep,” a company accounting log read. The same day, an employee in the Long Beach branch signed off on Al Thani’s request for the KHK plate, according to DMV records.

The prince later posted a photo of himself wearing a trucker hat adorned with a mini version of the KHK vanity plate.

Asked whether the car rental agency had bribed a DMV employee, Sajasi said: “I don’t think so.”

A DMV spokeswoman said certain records related to the plate had been purged, but that an internal review indicated “processes and procedures were followed.”

***

The summer before Al Thani’s senior year at USC, a member of his entourage took to Instagram to praise the prince as “the one who saved my life.”

“I’ll never forget the help and the support. Not today, not tomorrow and not even in a thousand year. Thanks God and thanks for sheik Khalifa bin Hamad al Thani,” Mado Khaled wrote in the 2014 post next to a smiling photo of the prince.

Khaled was a competitive bodybuilder from Lebanon nicknamed “the Puma.” He had worked as a personal trainer in Doha before joining the prince’s L.A. entourage, and referred to Al Thani on social media as his “boss.” He lived at the Beverly Wilshire and trained to compete at Venice’s famed Muscle Beach.

By 2014, Khaled needed a kidney transplant; he wrote on Instagram, “My profession of being a champion bodybuilder had taken its toll on my health.” Two former employees of Al Thani said Khaled told them steroid use was to blame. In the U.S., transplants are heavily regulated and patients can spend years on waiting lists.

A man from Egypt came to L.A. and moved into the Beverly Wilshire. At Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, one of his kidneys was transplanted into the bodybuilder. Khaled chronicled the experience online, posting a selfie with Dr. Stanley Jordan, the physician who heads the kidney transplant program.

That year, there was only one transplant at Cedars in which a noncitizen received a kidney from a nonrelative, federal records show. The government of Qatar paid for that procedure.

Agabus, the former chauffeur, and two other ex-employees said the man who provided the kidney was paid to go through with the transplant, though they did not know the exact source of the money.

Paying for an organ is a federal crime in the U.S. A Cedars spokesman said the hospital could not comment on Khaled’s transplant because of federal privacy laws, but that donors and recipients attest in writing that no money has changed hands.

Jordan said he remembered the bodybuilder’s transplant but denied knowing about any payment for the kidney. He said from his perspective, there was “no nefariousness” in the donation.

“We don’t have the ability to investigate those sorts of things, but we do ask that they give their word that this is not going on,” Jordan said.

Khaled did not return messages seeking comment. The man who provided the kidney stayed on in L.A.; a man who identified himself as his husband declined an interview request on his behalf, saying, “He’s really not into any sort of story.”

Al Thani’s lawyer, Keyko, refused to answer questions about the prince’s role in the transplant, but said any suggestion he had paid for the organ was “a serious allegation which appears to be unfounded and lacking in both evidence and connection to our client.”

***

Shortly after Khalifa Al Thani returned to Doha in 2015 with a bachelor’s degree, Cortes visited USC’s Annenberg School and inquired about the possibility of the prince getting a master’s degree, according to a school official.

The sheikh was admitted to a graduate program in public diplomacy, but the official said when classes began, Annenberg was informed that family duties prevented the prince from attending.

Professor Nicholas Cull, then director of the public diplomacy program, acknowledged that the prince got a “special dispensation” to study remotely, never granted to any student before or since. In lieu of classroom attendance, one professor agreed to text over Skype about the week’s topics with a person he was told was Al Thani. He said the exchanges lasted for an hour to 90 minutes once a week and he never saw the person’s face.

Social media of the prince during the period he was enrolled in the graduate program show him participating in military exercises on a handful of occasions. Many posts depict him engaged in leisure activities: relaxing at a cafe in the South of France, motoring through Monaco in a Ferrari, hunting with falcons in the Algerian desert, riding a dune buggy on a Doha beach, playing volleyball in a London park and skydiving in multiple locations in England.

When actor-rapper Tyrese Gibson visited Doha in 2016 — a week before final exams at USC — Al Thani played host, prompting the celebrity to write on Instagram, “Talking LA!!!!!!!! Sheikh Khalifa aka @khk went to USC for 4 years and he’s saying great things about my city!!!!!”

Cull, the graduate degree director, defended the atypical arrangement, saying the papers Al Thani submitted were “of a really high standard, potentially publishable.”

Professor Phil Seib, who has taught in the graduate program for more than a decade, said that he had long-standing contacts in the Qatari government, but was not informed that Al Thani was a student. He expressed dismay at the accommodation.

“That’s not what we do,” Seib said. “We’re supposed to be a world-class university. Students need to be in class.”

***

The four years Al Thani spent in L.A. were a payday for many. But not USC. Nikias traveled to Doha and visited the Qatar Foundation, the deep-pocketed nonprofit run by the prince’s mother, Sheikha Moza. He came away empty-handed, university officials said.

The grant that USC sought for the Catalina Island marine center never materialized.

Still, Sheikha Moza and her husband, the now-former emir, were expected to honor the campus with their presence at their son’s 2015 commencement, according to faculty members and employees of the prince.

A section of Shrine Auditorium had been reserved for the royals, and a golf cart designated to squire them across campus.

None of the Al Thanis showed, not even the prince. The professors on the Shrine stage were left staring out at empty seats.

Times multiplatform editor Sam-Omar Hall contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.