Protests over police brutality and criminal justice reform intensify race for L.A. district attorney

Less than a week after video surfaced of a Minneapolis police officer pressing his knee into the neck of George Floyd, the man challenging Jackie Lacey for the office of Los Angeles County district attorney attempted to connect the tragic case to her record of failing to prosecute killings by police.

By late June, after weeks of unrest and protests over Floyd’s death that included demands for her resignation, Lacey joined other L.A. County law enforcement leaders in calling for the creation of a task force to investigate future police killings, a possible nod to criticisms that internal reviews are biased toward police.

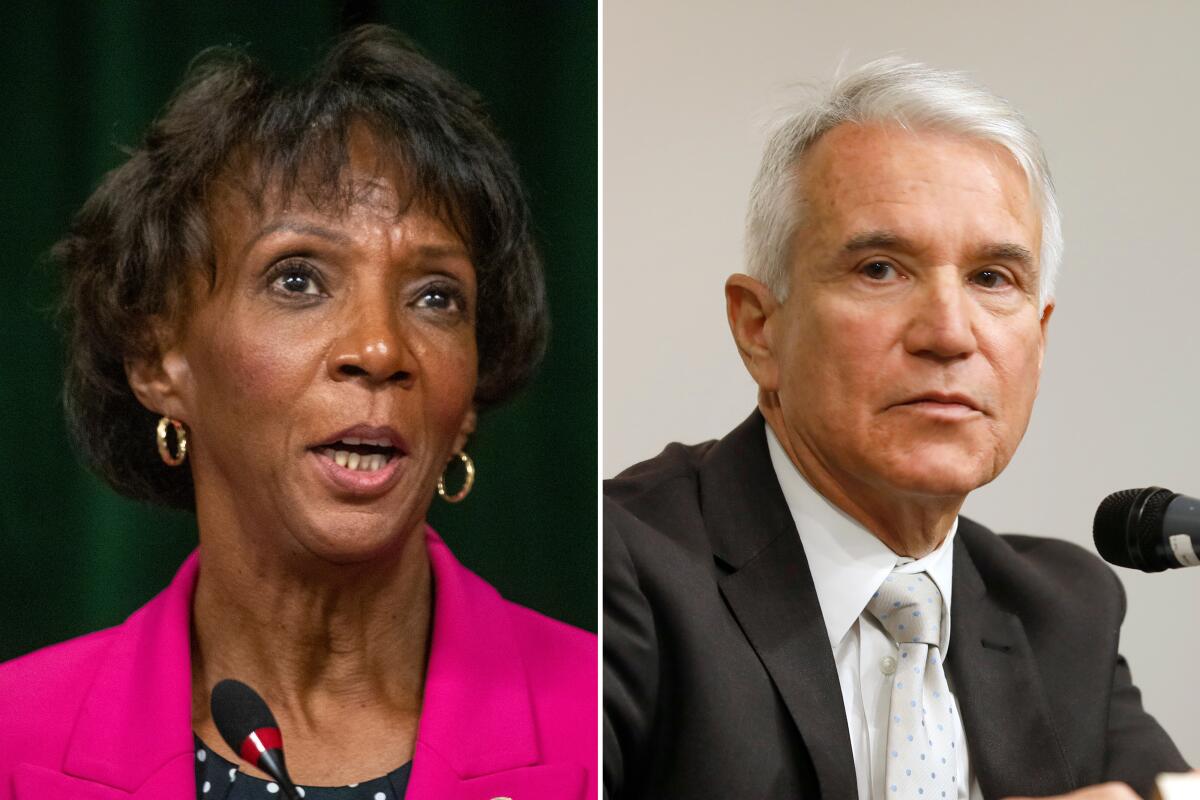

The November contest between Lacey and former San Francisco Dist. Atty. George Gascón to oversee the nation’s largest prosecutor’s office had already been framed as a test of appetites for criminal justice reform, with Gascón the flag-bearer for a nationwide movement to elect progressive prosecutors and Lacey representing a more traditional approach to crime and punishment.

But with hundreds of thousands protesting police brutality nationwide and the phrase “defund the police” moving from the fringes to a topic of debate for the L.A. City Council, the race is now being reshaped largely around which candidate is best poised to hold law enforcement accountable.

Recently, that has proved problematic for the incumbent. U.S. Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank) withdrew his endorsement of Lacey, citing the need to “end systemic racism & reform criminal justice.” Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti seemed to walk back his support of Lacey’s bid for a third-term last month, saying “it may be” time for a change in the district attorney’s office.

“In this moment, when policing is on trial so to speak, and some municipalities across the country … are talking about approaching public safety and law enforcement through different models, what [Lacey] represents is certainly out of step with people who are taking to the streets,” said Darnell Hunt, a professor of social sciences and African American studies at UCLA.

Attorneys for Los Angeles on Tuesday argued against a temporary restraining order to block police from using batons and tactical bullets to control crowds.

The momentum shift seems especially dramatic for a contest Lacey nearly captured three months ago.

Lacey secured 48.65% of all votes cast in the March primary, falling just shy of the majority she needed to avoid a runoff. Gascón tallied 28% and former public defender Rachel Rossi took home 23% of the ballots. Political consultants were quick to chastise Gascón for entering the race too late and questioned whether his campaign had failed to broaden his appeal beyond activists.

But Floyd’s killing appears to have dramatically increased the size of the reform movement that Gascón will need to energize his upset bid. Thousands have taken to Los Angeles’ streets for demonstrations against police brutality in recent weeks, sometimes marching on Lacey’s office or home. Nationally, two-thirds of Americans now say they support the Black Lives Matter movement, according to a recent Pew Study.

Asked about the effect the reform movement might have on the race, Lacey pointed to polling that suggests the slogan “Defund the Police” is unpopular, while noting other issues may be of equal importance in voters’ minds five months from now.

“Yes, people are going to be talking about social justice and reform, but I think in the end, the majority of voters who show up in November are going to be equally concerned about their safety,” said Lacey, who has often criticized Gascón as being soft on crime. Statistics show violent crime increased in San Francisco and Los Angeles County while both were in office.

Locally, attitudes about policing that were once derided as radical have begun to gain traction with established politicians. City leaders are considering cutting as much as $150 million from the LAPD’s budget, and a number of elected officials have condemned law enforcement’s at times violent methods of shutting down protests spawned by Floyd’s killing.

The Los Angeles Times has filed a lawsuit against Los Angeles County, alleging that the Sheriff’s Department has repeatedly refused to turn over public records about deputies involved in misconduct or shootings.

Lacey still retains strong support among law enforcement unions and boasts a raft of endorsements from some of California’s most powerful politicians, including Sen. Dianne Feinstein and Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance). San Francisco Mayor London Breed also spurned Gascón and endorsed Lacey last year.

Close ties to law enforcement, however, could become an “albatross” for Lacey if energy around criminal justice reform remains high through November, said Jody Armour, a law professor at USC.

“Those kinds of endorsements are under scrutiny now, in a way they never have been before,” he said. “It used to be something prideful, to have police union endorsements. Now it may be stigmatized.”

During the March primary, nearly all of the $2.2 million in outside committee spending that benefited Lacey came from law enforcement unions. Lacey has often been criticized for her reliance on union donations, an implication that police are buying favorable treatment from her.

Gascón recently joined a number of prosecutors in calling on the State Bar of California to preclude elected officials from accepting financial support from law enforcement unions, calling it a conflict of interest. Lacey rejected the idea.

Dustin DeRollo, a spokesman for the Los Angeles Police Protective League, said he believes any incumbent would naturally face an uphill battle in November during a time when calls for reform are popular. But he noted that a successful district attorney has to balance public safety with accountability, and argued Lacey is far more qualified to accomplish both.

“There’s really only one candidate on the ballot that’s going to be able to keep neighborhoods safe while also continuing good work on reform at the local level like dealing with mental health reforms, as Lacey has done,” he said.

Brian VanRiper, a political consultant who has worked on numerous Los Angeles City Council races, also warned that consistent messaging from police unions about issues of homelessness and property crime that plagued Gascón in the Bay Area could shift the focus to public safety.

“In their heart of hearts, most voters want to be safe,” VanRiper said.

Experts and consultants say the records of both Lacey and Gascón on accountability will be ripe for scrutiny after recent protests. Although both candidates filed dozens of cases against police officers for misconduct during their respective terms, charges against officers for on-duty killings were extremely rare.

Gascón declined to prosecute any officers for fatal uses of force in San Francisco, including the killing of Mario Woods, whose death garnered national attention. Lacey has also rarely brought charges in high-profile shootings, including one case when former LAPD Chief Charlie Beck asked her to prosecute. She did file manslaughter charges against a sheriff’s deputy in late 2018, however, and also recently decided to prosecute an LAPD officer caught on video beating an unarmed homeless man.

Asked about his record, Gascón has said he was hamstrung by state law that severely limited when an officer could be charged for using fatal force. An Assembly bill modifying that standard, which was signed into law last year, was supported by Gascón but not Lacey. Gascon has said he would have charged the officer who shot Woods under the new law.

“Her failure to take action and hold police accountable has been a subject of conversation for a long time here, namely by the Black community,” Gascón said. “I think what is happening now, after the Floyd case, is people who would not traditionally be paying attention to this issue, are.”

Lacey said the law change has not led to a rush of charges against officers and that Gascón was trying to take advantage of the movement to get himself elected.

“He keeps saying, ‘Hey, I woulda, coulda, shoulda,’ but he didn’t. I feel like he’s out there jumping in front of the Black Lives Matter parade, painting himself almost as their answer. Vote for me and I would have prosecuted some of these officers,” she said. “I think ... you kind of need to be incredibly naive to believe it.”

Gascón has leaned more heavily into the recent protest movements than Lacey. He urged Lacey and City Atty. Mike Feuer not to prosecute nonviolent demonstrators arrested for curfew violations, while criticizing the LAPD’s use of force to end demonstrations.

Lacey has also shown some deference to the movement. In addition to the proposed creation of the task force that would investigate police killings, Lacey said she would not prosecute anyone for dispersal order or curfew violations. She also ordered her office’s investigators to cease using carotid restraint holds.

Armour said that although both candidates have records that might not sit well with voters frustrated by police violence, Gascón is probably more appealing to a progressive electorate.

“You’re not gonna find many people with an immaculate record. So will the defund-the-police people ... say that George Gascón has enough daylight between him and Jackie Lacey that I can feel decent about supporting him, or even good about supporting him as the alternative?” Armour asked. “Gascón can make a plausible case for being that kind of candidate.”

If Gascón is to topple Lacey, he will probably need to capture many of the voters who supported Rossi, who also espoused a reform agenda during the primary. Voter data shows Lacey trounced Gascón by 15 to 20 percentage points in a number of demographics in March, including majority Black and Latino voting precincts and households earning less than $60,000.

But with Rossi’s voters, Gascón would gain a significant edge. Combined, Gascón and Rossi would have bested Lacey 56% to 43% among households earning less than $60,000 annually, and 54% to 45% among Latino voting precincts. Lacey would still hold a slight edge, 51% to 49%, among majority Black precincts. With the White House in play in November, a surge of progressive voters seeking to drive President Trump out office could also benefit Gascón.

Rossi said she has had discussions with Gascón’s campaign about a possible endorsement, though she’s still evaluating getting involved in the general election. No matter what she does, Rossi believes Floyd’s killing and the fallout that followed ripped open a wound that can’t be sewn shut by November.

“It feels different,” she said. “The population of the people involved in the protests seems different. It seems broader.”

Times staff writers Priya Krishnakumar and Dakota Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.