In the COVID-19 era, they become U.S. citizens in a drive-through

For nearly three decades, Luis Osorio dreamed of becoming a U.S. citizen. In the spring, Osorio, who left El Salvador 27 years ago, thought he was finally there. That was before the coronavirus shut down much of the country, and two ceremonies in March were postponed.

On Tuesday, he finally got to take the oath to become an American. It didn’t exactly go as the 47-year-old had dreamed. It didn’t even go as Osorio had imagined it would in the COVID-19 era: people socially distanced in a large room with American flags and a big screen for a virtual ceremony.

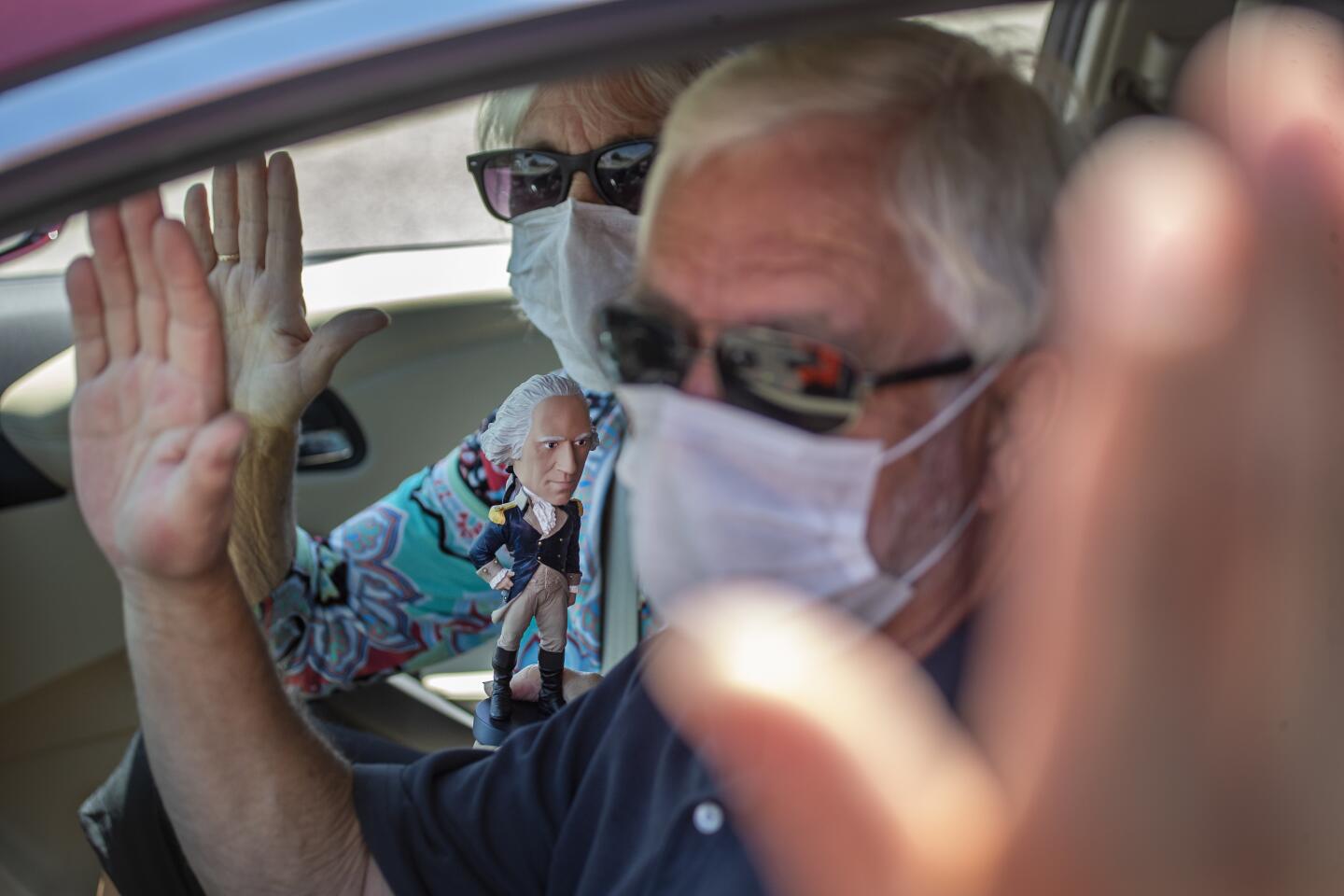

Instead, Osorio got to raise his hand in his blue Toyota Yaris in a drive-through in Laguna Niguel that some people mistook for a coronavirus testing site. As he held on to a certificate and a tiny American flag, Osorio was grateful all the same.

“I feel like a part of this country,” he said. “I can represent my country.”

Since early June, newly minted Americans have been coined via drive-through naturalization ceremonies set up by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to protect against the dreaded coronavirus.

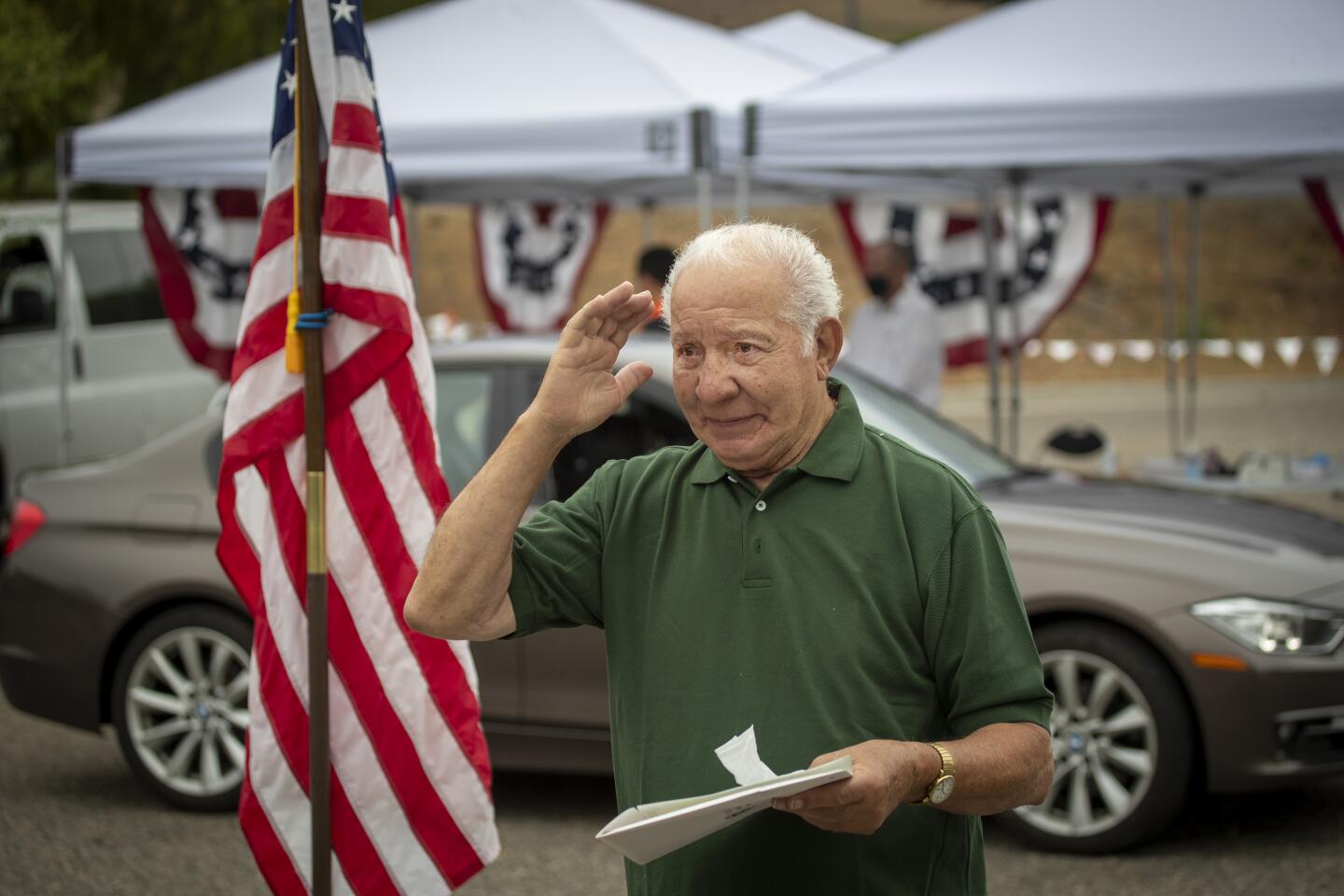

In this Orange County town, U.S flags hung from pitched-up tents, and the faint sound of “The Star-Spangled Banner” rang out from cars. Guests could tune their radios to hear patriotic music and a message from President Trump that was played as a video during typical ceremonies. Officials in traffic vests guided visitors through a monumental process that took less than 10 minutes.

At the end of the line, would-be citizens would be given the oath from a safe distance.

The ceremony happened even as visa restrictions make it harder for many immigrants to come to the U.S.

On Monday, President Trump expanded visa restrictions and bars on green cards to target immigrant workers who pose “a risk of displacing and disadvantaging United States workers during the current recovery.”

Osorio’s wife, Jossline, remained hopeful that her path to citizenship would continue.

“It’s been difficult because all of the sudden they’ve said they’d stop processing for green cards,” she said. “I’ve been waiting for six to seven months now.”

As for the speedy drive-through process Tuesday, Sofia Wolters, a 52-year-old Dana Point resident from Germany, didn’t mind it.

“It’s strange. You can look back at this unique event that you got to participate in. It’s kind of historic,” Wolters said. “It’s a negative that you don’t get the impact of the full ceremony, but you can also say, ‘Hey, I was a part of the COVID-19 process.’”

The strangeness of the ceremony, and the oddly individualized experience that it provided, pleased some of the new Americans and their families.

Jacqueline Franciose, a Tustin resident, cranked open the window from the back seat to video her stepfather going through the oath.

“When my mom and I naturalized, we weren’t able to take videos, and we were packed in like sardines, so at least it’s more personal,” Franciose said.

Franciose was glad there was a photo stop at the drive-through, and even happier after she successfully scrambled to find an American flag pin to adorn the jacket of Luis Cervantes, her 63-year old stepfather, who immigrated from Mexico three decades ago.

Iman Hanouneh, a 43-year-old Yorba Linda resident, immigrated from Jerusalem in 2009 to escape the conflicts there. She moved to the U.S. to raise her children, who could not attend the ceremony because they suffered from asthma, a condition that could make them vulnerable to COVID-19.

“It’s sad. This was not the ceremony I expected, but they have a big risk if they come,” Hanouneh said.

In normal times, the ceremony features a jumbo screen and more than 10,000 people in the Los Angeles Convention Center, USCIS Public Affairs Officer Claire Nicholson said. Now, about 300 people stop by the tents a day to finalize the citizenship process.

“These naturalization ceremonies are a culmination of a life journey for some people and just the beginning for others,” said Trung Vo, USCIS Santa Ana field office director. “We’re honored to be part of the lawful immigration process and included in their special day.”

Even as she became a citizen, Lindha Larsson, a 47-year-old Irvine resident, wondered whether her mother in Sweden would be able to immigrate to the U.S. when she gets older.

“I’m her only child, and I’m the only one who can take care of her,” she said.

Despite the anti-immigrant sentiments that seem to have become more pronounced throughout the U.S. in recent years, Cervantes said he felt valued in a country he has called home for decades.

“I feel free here in this country. I have more opportunities,” Cervantes said. “And I wanted to be able to vote.”

Brian Gebel, a 26-year-old who immigrated from Argentina at the age of 15, was glad to finally be a citizen. He said he couldn’t wait to vote.

“It feels good to actually have a voice now. It’s a huge blessing,” Gebel said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.