Shutting down California was a challenge for Newsom. Reopening could prove even trickier

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Gavin Newsom stood in the state’s emergency operations center March 19 and announced an executive order that would change the course of California history, requiring residents to remain in their homes as the coronavirus spread around the world.

California became the first state to tell all residents to stay at home amid the pandemic. Newsom’s decision sparked some controversy and a few lawsuits but has been credited with slowing the spread of the coronavirus and allowing California to avoid larger death tolls seen in states with early outbreaks, such as New York and New Jersey.

Now, three months later, the governor is in the middle of a test that could prove even more challenging than closing California: reopening it.

Newsom has given counties the green light to open their business districts again, with high-risk places such as hair and nail salons, gyms and bars opening their doors with myriad safety rules.

The pace of reopening has drawn criticism from some. But even as COVID-19 case numbers and hospitalizations soar, the Democratic governor and his health team insist that the data are in line with their expectations and the state is equipped to handle new cases.

“We are confident in our capacity, in the short run, to meet the needs of those most in need in the state of California,” Newsom said Wednesday.

In a sign that Newsom and his health advisors are worried that residents aren’t carefully stepping back into the world, the administration ordered all Californians to wear face coverings while in public or high-risk settings.

The move underscores the fluid nature of reopening and is a sign that the governor will need to constantly monitor — and may need to refine — California’s coronavirus strategy as metrics change and if new outbreaks occur.

With many of the restrictions loosened, the state is at another inflection point in the crisis, with more difficult decisions ahead.

“It absolutely worked, there’s no question,” Dr. Karen Smith, an infectious disease specialist and former director of the California Department of Public Health, said of the governor’s stay-at-home order. “Unfortunately and predictably, as we release people to go back to more of a normal life, you’re starting to see increases in cases.”

Newsom held fast to his executive order for seven weeks as the economy faltered and political pressure mounted for him to end what critics described as a draconian rule. But after weeks of stable hospitalizations and growing pushback against restrictions, the governor altered his approach in May — issuing more than a dozen changes to his stay-at-home order and guidance allowing businesses to reopen with safety modifications and county approval.

Newsom’s original two-page executive order from March required state residents to heed the directives of the California Department of Public Health and stay home unless they worked in one of 16 critical sectors outlined by the federal government. Californians were allowed to go out for food, prescriptions and healthcare but were told to maintain a distance of at least six feet from one another.

“The California Department of Public Health looks to establish consistency across the state in order to ensure that we mitigate the impact of COVID-19,” the order said. “Our goal is simple, we want to bend the curve and disrupt the spread of the virus.”

At the time, Newsom expressed confidence that Californians would “meet the moment” and stay home to protect public health.

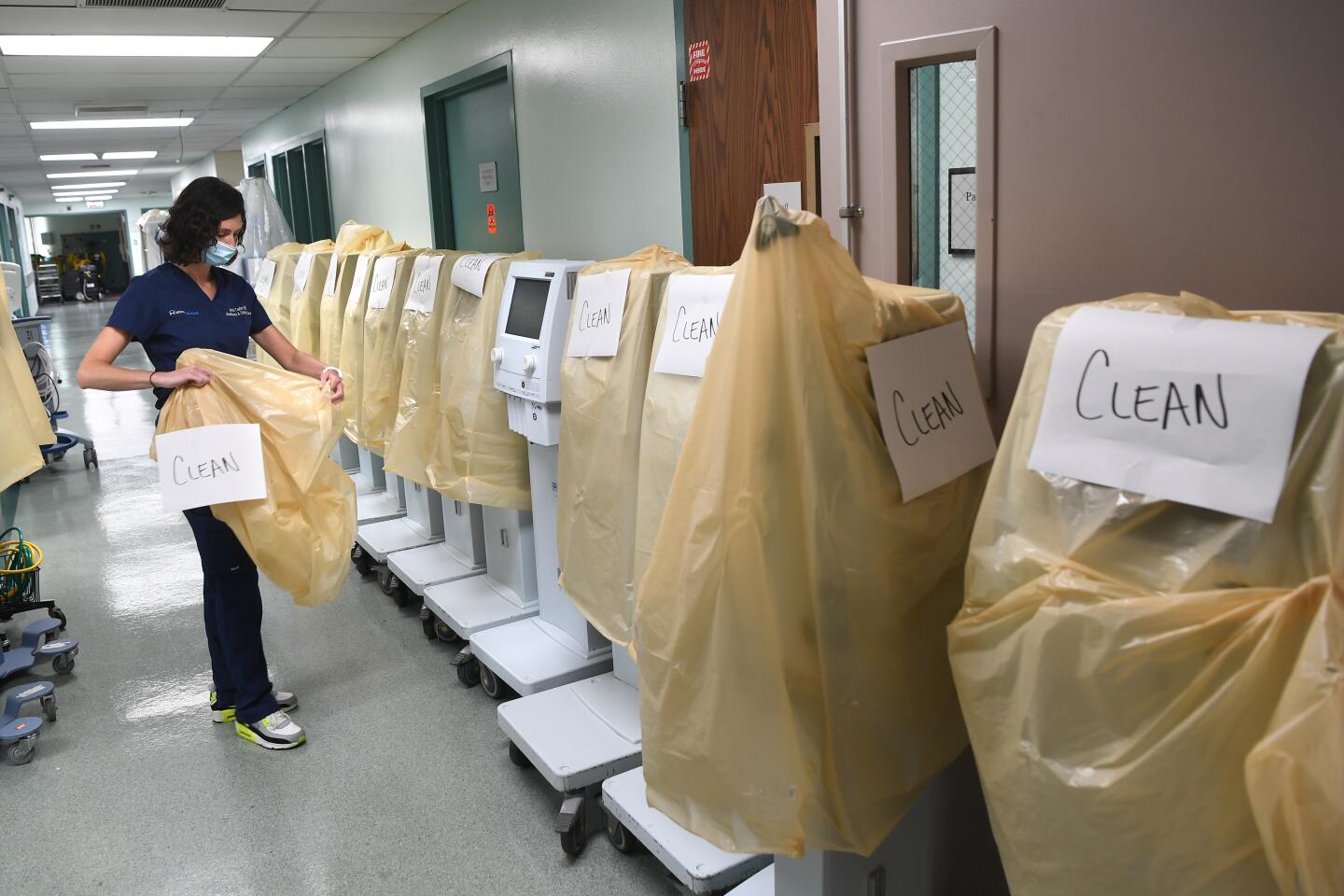

Health experts say the order succeeded in allowing the state to avoid an immediate surge of COVID-19 patients, buying enough time to purchase more personal protective equipment and prepare the healthcare system.

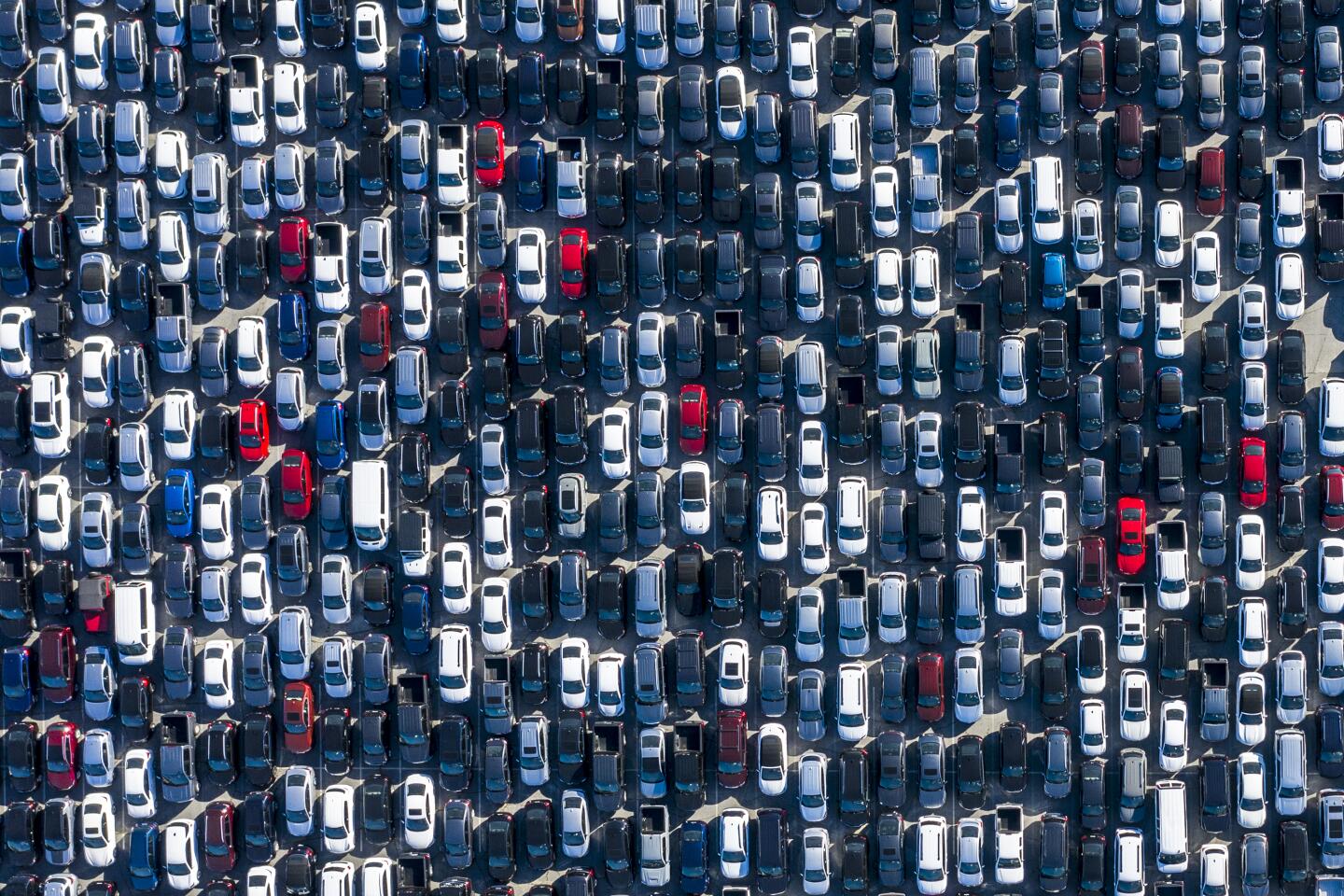

But that success came with an economic cost: More than 5.5 million Californians have filed for unemployment benefits, and the most recent state data show a jobless rate of 16.3% in May.

As political pressure grew, the Newsom administration on April 14 introduced six indicators that the state would need to meet before beginning to loosen the order. Two weeks later, on April 28, the governor unveiled a four-stage reopening plan, that would allow certain businesses deemed a lower risk for transmission to open first.

Then, on May 8, without a detailed accounting of how the administration’s criteria had been met, the governor began implementing his plan and easing the restrictions. Bookstores, music stores, toy stores, florists, sporting-goods stores and other retailers opened for pickup, and retail manufacturing and logistics were allowed to resume operations statewide.

Amid protests in Orange County and the state Capitol and open revolt in several rural communities, the governor also gave more power back to counties, allowing areas that had met certain guidelines for testing capacity and slower growth in positive cases to reopen more quickly.

The decision to allow counties to move at their own pace once they met benchmarks set by the state rapidly sped up the reopening process in May. Ten days after implementing the original criteria for counties to reopen, the governor loosened the rules to let most counties in the state qualify to open restaurant dining rooms, shopping malls and other businesses.

By the end of May, at least 47 of 58 California counties had met the state’s standards and began transitioning to the third stage of the governor’s reopening plans, with the return of hair salons, barbershops and church services, Newsom said. In the second week of June, gyms, day camps, bars and some professional sports were reopening across California.

When Newsom adopted the stay-at-home order in March, the state health department reported 675 positive cases and 16 deaths from the coronavirus in California. On Wednesday, state officials reported more than 190,000 confirmed cases and 5,632 deaths.

Newsom last week offered a full-throated defense of his decision-making.

“Localism is determinative,” Newsom reiterated, a line frequently used at his news conferences on the coronavirus to emphasize his position that counties — and not the state — should determine when it’s safe to reopen.

“We have to recognize you can’t be in a permanent state where people are locked away — for months and months and months and months on end — to see lives and livelihoods completely destroyed, without considering the health impact of those decisions as well,” Newsom said.

Newsom has frequently compared reopening businesses to gradually lighting a room with a dimmer switch. He has also talked about how the state may need to “toggle back” but has not provided details on what would happen if problems persisted in particular counties.

Dr. Mark Ghaly, secretary of California’s Health and Human Services Agency, said Monday that the Newsom administration is working with Los Angeles and 10 other counties that are experiencing increases in cases, running low on intensive care unit beds or otherwise failing to meet some of the regional criteria set by the state to reopen businesses and address the pandemic. Ghaly said the administration is offering state support, such as additional healthcare workers or ventilators.

During an appearance last week on “The Late Late Show with James Corden,” Newsom was asked what it would take for him to consider reinstating his stay-at-home order. He pointed to spikes in the state’s data.

“I think to start seeing a sharp increase in the positivity rates, the percentage of people that are testing positive, to see a big spike in hospitalizations and in ICUs,” Newsom said. “California is very well prepared at the moment. But again, if we start to see spikes over a consistent period of time, that’s when we’ll start putting that dimmer switch [on] and start pulling back.”

As Newsom has shifted responsibility for reopening to local leaders, state Sen. Steve Glazer (D-Orinda) said he believes it’s the state’s responsibility to improve its data to quickly and accurately pinpoint outbreaks and stop the spread of the virus.

“I don’t believe you can count on positivity rates based on just counting tests,” Glazer said. “The state should know the rate of infection and changes, and the state should know where the spread is coming from. Today, 90 days in, a positivity rate on a test that one chooses to take is not community surveillance by any means.”

The Bay Area lawmaker also said hospitalization data do not help officials take action to immediately contain outbreaks because patients are sometimes hospitalized weeks after being infected. Glazer commended the governor’s work but said the lack of data at the state level makes him worried that California could be reopening too quickly.

Smith, the former California Department of Public Health director, questioned whether residents will abide by stay-at-home orders again if cases spike, or if local leaders will have the political willpower to force people indoors again without Newsom leading the way. Protesters have targeted local health officials, sometimes rallying outside their homes, in an effort to push back against coronavirus restrictions.

“In the next couple of weeks, things are either going to start to get better or we’re going to reach a tipping point,” Smith said. “If we do need to reinstitute, even at county levels, we need that strong leadership, that consistent message coming from the governor. He can’t just not be present.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.