L.A.’s ‘social equity’ program for cannabis licenses under scrutiny

A Los Angeles city program crafted to ensure that cannabis sales licenses go to people from communities most harmed by the war on drugs has been hailed as a kind of reckoning with historic injustice.

It was designed with a lofty goal: Ensure that people affected by the government’s crackdown on the illicit drug trade become business owners in this emerging industry.

But the city’s “social equity program” is under renewed scrutiny over whether the initiative is fulfilling its promise.

The latest controversy centers around 4thMVMT, a company founded by a well-to-do businessman who partners with Black entrepreneurs to obtain cannabis licenses. The company positioned itself as one of the program’s biggest winners by partnering with at least 13 of the applicants scheduled to receive temporary approval this week to start operating after meeting certain conditions.

An attorney who reviewed one of 4thMVMT’s partnership contracts has raised alarms over what she says are “predatory” business practices baked into the agreements. Meanwhile, competitors of 4thMVMT have seized on the contract language to attack the company.

The contract allows a subsidiary of 4thMVMT to buy out the “social equity” partners if they refuse a “lawful direction/instruction” from the company, according to a copy of the contract reviewed by The Times. The buyout price is set at $200,000, an amount experts on the state’s cannabis trade say is far less than the likely market value of a licensed pot shop in Los Angeles.

“The intent of the social equity program is to create ownership for the applicant,” said Yvette McDowell, an attorney representing a person who signed a contract with 4thMVMT. “That sounds like an employer-employee relationship.”

McDowell also faulted city officials for failing to thoroughly vet contracts to make sure social equity partners would be in control of their businesses and receive the majority of the profits.

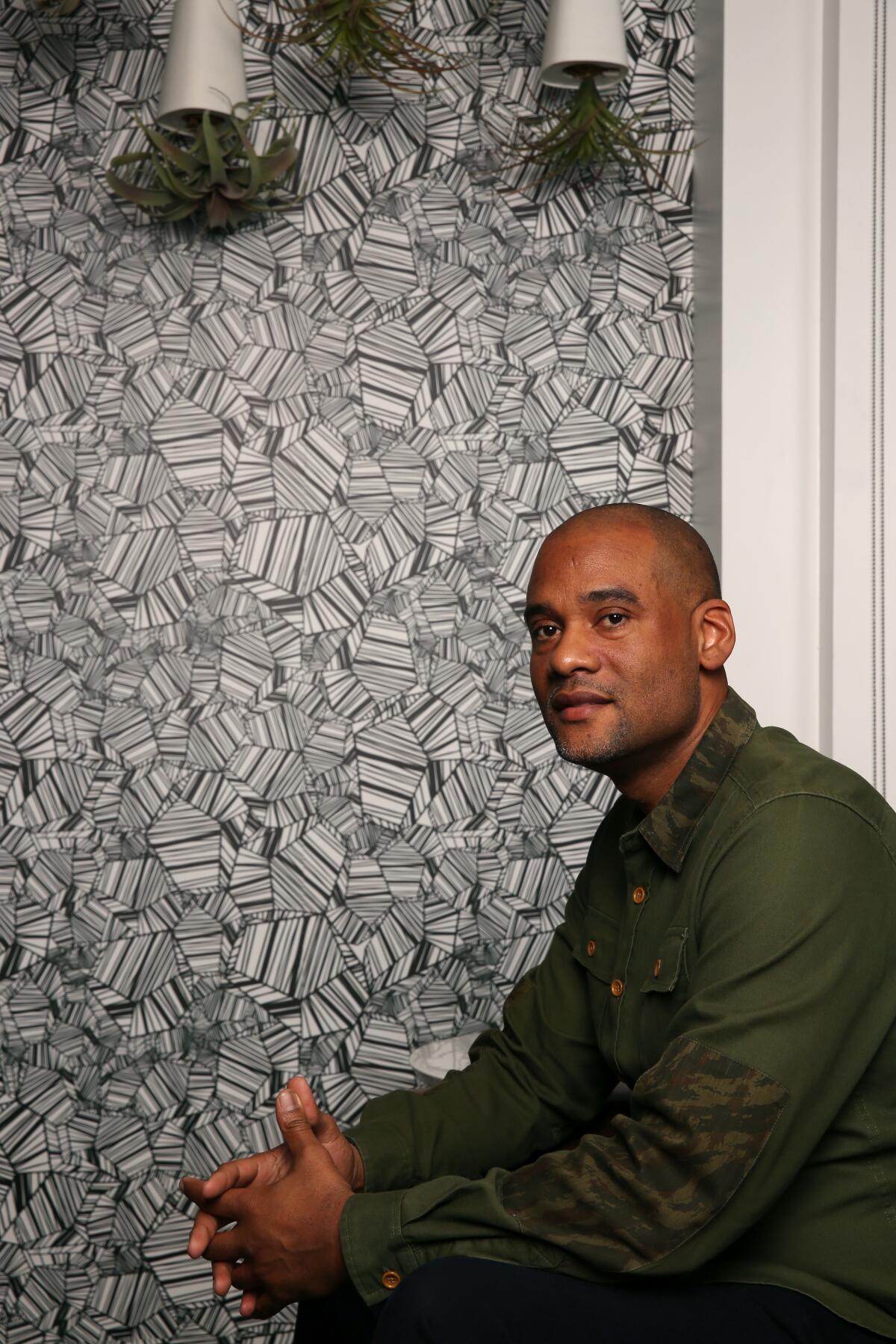

In an interview with The Times, 4thMVMT CEO Karim Webb said he planned to amend the contract language but bristled at any suggestion that the company would take advantage of a social equity partner.

“4thMVMT is not ... doing anything that’s predatory or that is not in the interest of our partners executing at the highest level,” Webb said. “We are going to address displacement with these folks and build generational wealth.”

Health officials say the total in new cases is not the best measure of community spread because of aggressive levels of new testing. They point to other metrics they say shows that the local outbreak has stabilized.

He said the contract’s buyout language was meant to protect the millions of dollars in investments he and others have made to launch the businesses, train applicants and rent real estate. The social equity applicants haven’t contributed money, he said, and the clause was necessary in order to attract other investors.

“That provision in our contract, more so than anything else, is an incentive not to sell,” Webb said. “And to behave properly. You’ve got a million and a half dollars into a property and somebody gets a dividend check and goes to [Cabo San Lucas] and doesn’t come back, you want to at least disincentivize that kind of behavior.”

James Bryant, general counsel for 4thMVMT, described the language as “harsh” and said it was drafted by another lawyer. He said 4thMVMT wouldn’t exercise a forced sale over petty business disagreements

“The forced sale is an action of last resort,” Bryant wrote in an email to The Times.

Bryant said the contracts are being amended so that 4thMVMT would have to pay “fair market value” to buy out a partner.

It’s unclear if other applicants have similar language in their business contracts.

The city’s department of cannabis regulation recently proposed new rules for the program, including changes intended to prevent “predatory” behavior from investors who partner with social equity applicants. The changes include barring any conditions that would force a social equity applicant to transfer his or her ownership.

Bryant said 4thMVMT would make sure its contracts comply with any changes in the city’s rules.

A department of cannabis regulation spokeswoman declined to comment on specific applications but said her agency conducted an initial review of applicant contracts and would conduct additional reviews as part of the licensing process.

Criticism over the social equity partner contracts is the latest controversy for the city’s embattled cannabis licensing program, which has been beset by delays and complaints of unfairness.

In September, the city launched a first-come, first-served online application process to decide who to give 100 licenses to operate new pot shops. Hundreds of businesses flooded the application portal within minutes.

Concerns that some accessed the portal before the official start time provoked an outcry. Other entrepreneurs complained that applicants with slower internet speeds were put at a distinct disadvantage.

An audit commissioned by the city found that some businesses had been able to log onto the application portal shortly before the start time but concluded that no one gained an unfair advantage. In April, a group of applicants sued the city, alleging that the process was “flawed” and unfairly implemented.

Some critics also have focused on Webb, pointing to his City Hall ties and questioning how he and his partners were able to secure more spots among the first 100 applicants than anyone else. 4thMVMT has signed the partnership contracts with 32 social equity applicants, including 13 among the top 100 that could receive temporary approval.

Webb was appointed last year to the city’s airport commission. And until February, 4thMVMT — pronounced “Fourth Movement” and named for a famous reference to African American economic equality — employed a son of Councilman Herb Wesson.

Webb has said the connections with City Hall didn’t give his applicants any advantage in the cannabis program.

The city’s social equity program considers various factors in deciding who qualifies as a partner, including income, past cannabis convictions and long-term residency of an area that was disproportionately targeted by enforcement of drug laws.

Several of 4thMVMT’s social equity partners have publicly praised Webb for giving them an opportunity they could have only dreamed of to build their own businesses. The partnership contracts give them an 81% stake in their cannabis businesses.

But some of 4thMVMT’s competitors are criticizing the terms of his partnership contracts.

Donnie Anderson, a founder of the California Minority Alliance, said the contract’s buyout provision shows that Webb was “doing to the community what’s been done to them forever. I’ve got a problem with that.”

Anderson’s group worked with dozens of social equity applicants. None made it to the first 100.

McDowell, the attorney for one of Webb’s social equity partners, said Webb also has refused to share other documents with her and her client, including a management agreement with another business entity. The partnership contracts say the firm will have the authority to run the day-to-day operations of the pot shops.

Webb declined to share a copy of the management agreement with The Times. However, Bryant said the partnerships would not be charged a fee for management of the stores.

McDowell, a retired prosecutor with the city of Pasadena, said it’s important to see those documents to determine whether Webb’s partners will receive an 81% share of profits.

Her client, who spoke to The Times on condition of anonymity, said Webb first showed his social equity partners the contract language at a gathering last year and gave them one to two hours to review and sign the document.

“There’s no way they could be given adequate representation when it’s either you sign it, or you don’t,” McDowell said.

She said her client was not among the top 100 applicants expected to be approved to run pot shops during the current round of license approvals and was no longer interested in working with Webb.

Webb said McDowell has been unreasonable and that he had little choice but to rush the contracts. There was fierce competition for real estate rentals, he said, and landlords waited to close the leases until just days before the city’s online application portal for licenses was set to open.

“If you’re uncomfortable signing it, don’t sign it, and I’ll call somebody else,” Webb said he told the group. “This is the opportunity, and I apologize that you haven’t had time, but we haven’t had time.”

A company spokeswoman who said she was present for the meeting said the applicants were told they could call their lawyer during that time.

Webb said the partnership contract has to be considered alongside 4thMVMT’s commitment to helping Black Americans own their own businesses, affording them the opportunities he and his siblings had growing up as the children of the owners of McDonalds franchises.

He and others with 4thMVMT emphasized that the business charges no fee for its services to the social equity partners and pays for months of training and assistance, help with real estate transactions and other services.

Webb, who has also launched Buffalo Wild Wings franchises, noted that there are only 18 Black social equity applicants among the top 100, and that all but five have partnered with him.

“The only thing I’m looking for is a business opportunity for Black folks to do what’s happened for me and my family,” Webb said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.