Before George Floyd, there was Stephon Clark. Here’s what his brother has learned about pain, protests

SACRAMENTO — With the National Guard carrying live ammunition and two nights of looting leaving the city on edge, no one was sure what would happen here Monday as darkness fell downtown — not police blaring reminders of a curfew from an unmarked car, not the city leaders and business people who had long since cleared out of the area, and not the protesters themselves, many seemingly young and inexperienced with civil disobedience.

Then a slight man, decked out in a tapered black suit, lace up loafers and a wide brim hat, stepped up as mobocracy crept in with the evening.

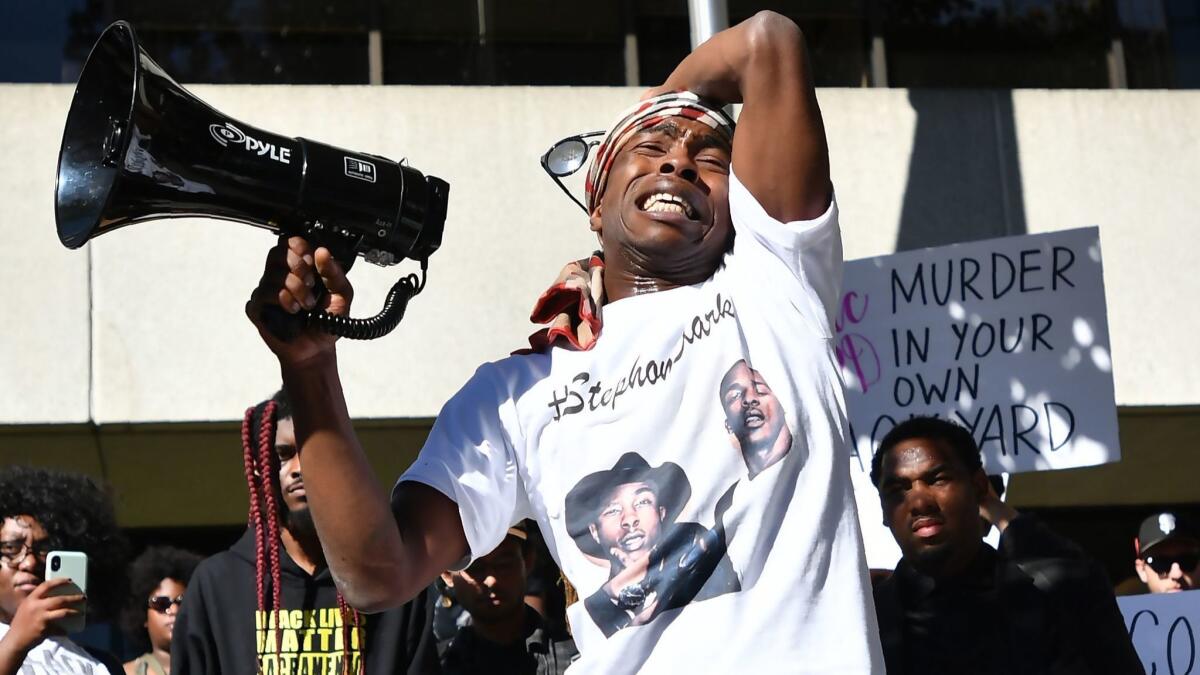

Stevante Clark, brother of Stephon Clark, gunned down by Sacramento police in 2018, took hold of the only small bullhorn anyone had thought to bring, and with it, took hold of the crowd of about 600.

“If you disrespect the legacy of George Floyd, you are disrespecting the legacy of my brother,” he yelled, his voice strained to a whisper from earlier protests. “And I will not allow that.”

Clark, 27, is emerging as the leader of a particular moment in Sacramento, able to clearly convey and share emotionally the salt-in-the-wound agony of police violence that has defined his life since his unarmed brother was killed in his grandmother’s backyard — a bellwether of grief for a young generation already tired of hurting and desperately in need of hope from someone who feels authentic.

But he is an unlikely guide. Two years of expressing his sorrow publicly in this city of 500,000 has included arrests, a mental breakdown involving a sword, humiliation and scorn, he said, leaving some nervous to have him back on center stage.

“He’s very genuine,” said Darrell Steinberg, who first met Clark in the days after his brother’s shooting when Clark jumped on the dais at City Hall and yelled obscenities at him, as the current mayor and former Senate president pro tem.

“There is a lot of good in there and yet he has his troubles,” said Steinberg. “He demonstrates how complex the human condition is.”

Police killed Stephon Clark after they responded to a call about someone breaking car windows. A sheriff’s department helicopter spotted him in a backyard, and two officers pursued and fatally shot him after seeing what would later turn out to be an iPhone in his hand.

The death came two years after Sacramento police killed another black man, Joseph Mann, in a case that led to massive reforms and the city’s first black police chief. The shooting of Clark, like that of George Floyd, provoked fury that men of color continued to die due to police violence, setting off massive protests that shut down the freeway and forced The Kings to cancel NBA games.

Last year, protests around Clark’s death helped to pass legislation changing California law, increasing the standard for when law enforcement can use deadly force from when it is “reasonable” to “necessary.”

A security guard with dreams of being a musician, Stevante Clark was thrown into the role of the grieving brother and spokesman for a movement when his brother died, but the pressure of national media attention coupled with the heartache of loss left him erratic and seemingly out of control.

Appearing on the Don Lemon show on CNN, Clark dinged a bell when he disliked a question, leaving Lemon flummoxed. At a memorial service with the Rev. Al Sharpton, Clark clung to the pastor and threw himself on the casket.

A few weeks after the shooting, he trashed a room in a hotel after watching video of it and was placed on an involuntary mental health hold by police, ending his ability to carry a gun and his security career.

He yelled profanities at a father and son in a local store. He disrupted a church service. He demanded city officials give him diplomatic immunity and a 24-hour auto detail facility.

He used trashcans to barricade the street where he lived and menaced roommates and neighbors with a machete in a three-day standoff, leading police to arrest him.

Public sentiment swung from sympathy to ridicule to fear. For a time, it was unclear if people were seeing righteous anger, grandstanding or mental illness.

Clark himself seemed unsure, though he now understands he was “knee deep in the grief,” he said.

But problems have persisted. Last month, he was arrested on three felony counts of domestic abuse, for which he has a June court date. Clark declined to speak about the incident.

“I am changing the ‘You have to be perfect’ narrative,” he said.

“I didn’t ask for this [expletive]. God dropped the ball, said ‘Here you go, let’s see what you can do with it,’” said Clark, sitting on metal bleachers at a baseball diamond near the Capitol on Tuesday morning, where he had used his social media following to gather volunteers to scrub graffiti, and where he was interrupted three times by passersby who wanted selfies.

“I’ve been broken. I am broken,” he said. “And I’ve noticed that to be built like a king, excuse my French, but you have to be broken like a [expletive].”

Clark is known for his raw and charismatic stream-of-consciousness rebukes of authority that, even as he has gained prominence in Sacramento and the Capitol, have made him little trusted among an old guard that is wary of his volatile ways and refusal to align himself with known players in a town of politics.

“Community leaders failed. Democrats failed. Republicans failed. Christians failed. Muslims failed. Everybody has failed these kids,” said Clark. “The anger is righteous anger.”

But, gentle and introspective away from cameras and followers, he said he has learned that “passion without direction is chaos,” and hopes to pass that lesson on.

“I know I may come off as a little eccentric. I have a foul mouth. I am an advocate for marijuana. I’m a civil libertarian. I’m known to go line dancing at country bars at times,” Clark said. “I’m not the most popular, liked guy. And I can accept that though because I am not here to be popular or liked. ... I represent the [expletive] struggle and I am going to die in this [expletive].”

That outsider nature has made him invaluable during the unrest, at a time when both community and political leaders are searching for a way forward in the face of unrelenting rage across the country. Protesters so far have had few clear calls to action, and even seasoned leaders with progressive credentials like Steinberg are struggling.

“The young people out there look, I think understandably, at everyone in positions of power as not knowing and not caring and certainly not understanding and maybe they are right,” said Steinberg. “And I am trying to figure out how I can be better.”

By noon Tuesday, Clark was at the facade of the California State Library, where anti-law enforcement graffiti was scrawled on its smooth stone walls and National Guard members still stood watch.

Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has also pledged to do better, was there as well, scrubbing in solidarity in a stained blue work shirt with a bottle of cleaner hanging from the back pocket of his jeans.

With typical impunity, Clark grabbed Newsom for an impromptu Facebook live — a rare unscripted moment for the careful politician who, along with other governors, earlier in the week had been berated by President Donald Trump for appearing “weak” in the face of unrest and failing to use military force to remove protesters.

Newsom, who seemed tired, also seemed thankful for Clark’s presence in a city that likely would have made national headlines if protesters had squared off with the National Guard. There is consensus here that Monday night may have ended with clashes if not for Clark.

“You more than anyone understand the rage that people have,” Newsom said into Clark’s camera. “And [understand] this madness, but ... in a thoughtful, peaceful and constructive way.”

After taking the bullhorn that night, Clark led protesters to Sacramento County Dist. Atty. Anne Marie Schubert’s office, a place familiar to local activists, who have long contended that she is easy on officers who use lethal force. She declined to charge the officers who shot Stephon Clark.

Clark ordered the crowd to take a knee and raise their fists as he recited names of people killed by police violence and institutional racism, back to Emmitt Till.

“Give me your hand. Give me your mind. Give me your spirit. Give me your heart,” he yelled. “We can protest and whatnot, but what are we asking for?”

He wants Schubert recalled.

Then he ordered the crowd to look to their left, look to their right and introduce themselves to their neighbors, like a pastor in church.

Nearby, a young white man dressed in all black with red tennis shoes turned to the girl next to him.

“Hi, I’m Josh,” he said.

Clark wants these protesters united in “plotting and planning and mobilizing and strategizing,” he said. He wants them to call for more police reforms, and for California’s new use of force standard to be adopted nationwide.

By 10 p.m., Clark had ordered protesters to make the area a “ghost town” rather than fall into what he described as the “trap” of massive law enforcement presence. About 50 people were ultimately arrested, mostly for curfew, but the stealing and vandalism of previous nights didn’t materialize, and hasn’t since.

“I am able to move like water in [the protests], because I have paid the price for my agenda,” said Clark.

Clark said he hopes to capitalize on his current prominence by holding regular Sunday rallies and revitalizing a reform movement that ebbs and flows with public outrage. He is quick to tell followers the events will be as big and organized as those of Bernie Sanders or Trump, and makes sure every person he meets is following him on Instagram.

That these violent uprisings and peaceful protests are happening all over California speaks to something black people know well and others ignore.

Clark is almost always pushing his message, though late last year, after the passage of the state’s use of force law, he swore he was done.

“I’ve been tired since my brother died. I’m exhausted,” said Clark.

He was, he said, going to step out of the spotlight and figure out what his future looked like outside of his brother’s legacy, maybe focus on his music.

But then Floyd was killed, and the ending bled into another beginning.

“I hate my life sometimes,” said Clark. “But it is what it is. I am in pain. I speak to pain. I speak to hurt.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.