Voices from the protests: ‘People of all races out risking their lives to march’

Sean Welch’s homemade T-shirt said it all: “DYING BREED” was scrawled across his chest in red and black, just above the name of George Floyd, who died in Minneapolis a week earlier after a white police officer pinned a knee on his neck.

That’s what brought the 40-year-old West Hollywood apartment manager to the protest at Laurel Avenue and Sunset Boulevard late Monday afternoon. Anger and mortality. His own and that of millions of others like him. Black men in America in the 21st century.

“We a dying breed out here,” said Welch, who was 12 and living in South Central Los Angeles the last time National Guard Humvees rolled through the streets. That was 1992, when the city burned after four L.A. police officers were acquitted in the savage beating of Rodney King.

“Cops have been killing us for years,” he said, as a crew of disaster recovery workers boarded up a furniture store behind him. “What makes them believe it’s OK? People don’t even realize it until it has some massive effect like this.”

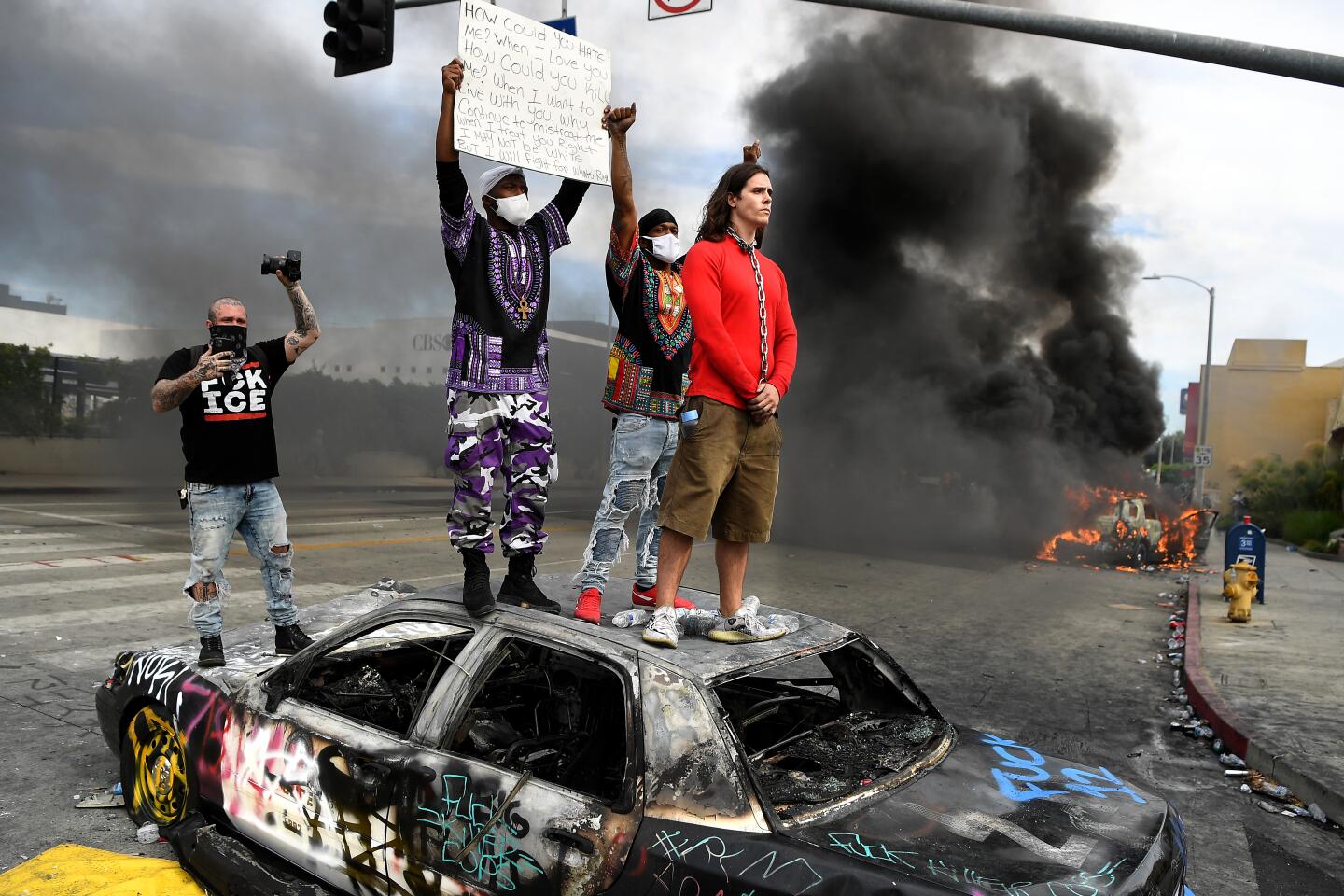

“This” being thousands of Americans drawn to the streets from coast to coast, day after day since May 25, protests that tend to start out peacefully and often devolve into tear gas and riot gear, vandalism and looting, fear, injury and arrest.

The women and men demonstrating on Southern California streets have been as varied as their motives — a mix of ages and races and ethnicities, fueled by anger at needless death and at inequality laid bare by a pandemic whose victims have been disproportionately low-income people of color.

As darkness falls, it can be difficult to tell protester from agitator from opportunist. One thing is certain: They are all there.

“We are seeing people who are out because they’ve been pent up for months due to the stay-at-home order and intent on causing anarchy,” said Allissa V. Richardson, author of “Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones and the New Protest #Journalism.” “There are factions from either left or right interested in using the Black Lives Matter name to discredit the movement.

“But then you have genuine concerned citizens willing to risk their lives in a pandemic,” said Richardson, a professor of journalism at USC. “There are not just bad actors but brave actors. People of all races out risking their lives to march. They know they could bring home the disease, but they say this is important enough to come out after more than 10 weeks of sheltering in place.”

L.A. Police Department spokesman Josh Rubenstein said the agency was still learning about the protesters, and could not immediately comment on the makeup of the crowds. David Colker, a spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, said the group had no information about anarchists or white supremacists at the protests.

When Amma “Satomaa” Fordjour headed out Saturday to attend her first-ever protest, organized by the Los Angeles chapter of Black Lives Matter, she didn’t expect to end up helping lead more than 1,000 people for 12 miles into Beverly Hills.

At noon, she was at Pan Pacific Park in the Fairfax District. Protesters peacefully headed west toward the Beverly Center, where organizers stopped to give speeches and lead chants. At Fairfax Avenue and Third Street, she saw an LAPD cruiser in flames. She carried a sign painted with the face of Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old black woman found hanged in a Texas jail cell three days after a state trooper pulled her over for failing to signal a lane change.

Locals waved from their patios and cars honked in support. Police gave them space. On Rodeo Drive, people knelt and listened to more speeches. But by 5 p.m., Fordjour was in a Lyft vehicle heading back to her car at Pan Pacific Park, watching people drive up and start looting.

“It was frustrating to see five hours of nothing but positivity and to get in my car and know that I was driving away from violence,” she said Monday. She was saddened, she said, that the lasting images of the protest would be police vehicles on fire and vandalism that was mostly disconnected from the heart of the event.

“I personally do not want to be anywhere in public because of violence,” she said. “Now I’m sitting at home because I’m scared.”

Cerys Rotoneo, a 19-year-old political science student at Cerritos College, and Guadalupe Juarez, 18, had originally planned to protest Monday near Los Cerritos Center and help raise money for a nonprofit organization. But when the event went viral, they worried about the effect of outsiders on their peaceful protest.

“So we were, like, we should probably change the location, just to make sure that looting doesn’t happen and so forth,” Rotoneo said. Dozens of sheriff’s deputies still staged in the mall’s parking lots and blocked off entry points, fearful of looting. But other officers traveled with the protesters, on foot and in squad car, as they walked to City Hall and chanted.

“This is not about us. This, it is not about politics, nor is it about our opinions,” Rotoneo told about 100 people gathered in Gridley Park before the march. “This is about morality and humanity and our efforts to stand together in unity for Black Lives Matter.”

Tia Reed, a 30-year-old child psychologist who lives in Northridge, showed up at 7:30 a.m. Monday knowing that the protest near the LAPD’s Van Nuys Station had been canceled. It would have been her first demonstration.

It was still important, she decided, for her and her friends to make their voices heard. So they moved their protest to a more visible location a few blocks away. By early afternoon, microphone in hand, Reed was leading the crowd.

“No justice!” she shouted.

“No peace,” dozens of people responded.

“There’s no hard feelings toward peaceful cops,” Reed said in an interview. “There’s no hard feelings toward anybody in the world that’s peaceful. Our feelings are toward racism and police brutality.”

Sometimes protesters argued with each other over tactics and what they were trying to achieve. Reed said some looters showed up about 10 a.m. and started tagging buildings, and she and her fellow protesters demanded they leave. Across the street from the protest, several men leaned against the boarded-up front windows of the Country General Store. Other businesses in the areas had also boarded up their windows.

“Everybody handles their pain in different forms,” she continued. “So I don’t really want to speak up on that. But at the same time, there’s a way of handling and conducting business to be heard. And looting is not one of them, and vandalism is not the other. I just want us to have a peaceful protest and you know, say it loud.”

A South Los Angeles high school senior who asked to be identified by just her last names to avoid retaliation also went out to protest — peacefully — in the wake of Floyd’s death. Hernandez Cruz had been attending protests for more than a year, since she joined the ACLU’s youth liberty squad. And nothing, not even her parents, could keep her from the Fairfax District on Saturday.

Hernandez Cruz said that police got aggressive and began hitting people with batons. She sustained an injury to her head, just above her right ear. It took six stitches to close, and she suffered a concussion.

The 18-year-old has a week left of high school, but as of Monday wasn’t able to use her computer to finish the remainder of her schoolwork yet — her head feels tight, it’s hard to move her neck and she’s not supposed to look at screens.

Hernandez Cruz said she attended the protest to support the people she sees as part of her community. She wants the police defunded to prevent further violence from the law enforcement community. She hopes that her actions will play a role in the arrest and first-degree murder conviction of the four police officers involved in Floyd’s death, at the very least.

“I’m a Latina and it’s like ... where I live, we’re all united and I feel like we should all speak up for one another and be there for each other,” she said. “At times it does get me really mad because it’s like we don’t deserve this. … black people and immigrants basically built this country and now people are getting mad that we’re standing up.”

And yet, she said, she still has hope.

“I know it’s been happening for centuries, but if we continue to apply pressure on the cops and the system then I feel like something will be able to change. Even if it’s small, it’s still progress,” she said. “Eventually something will happen. We just all have to stay together ... my parents have gone through this, my grandparents have gone through this.”

Times staff writers Dakota Smith, Andrew Campa, Ruben Vives and Seema Mehta contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.