Olvera Street merchants struggle to survive amid the coronavirus pandemic

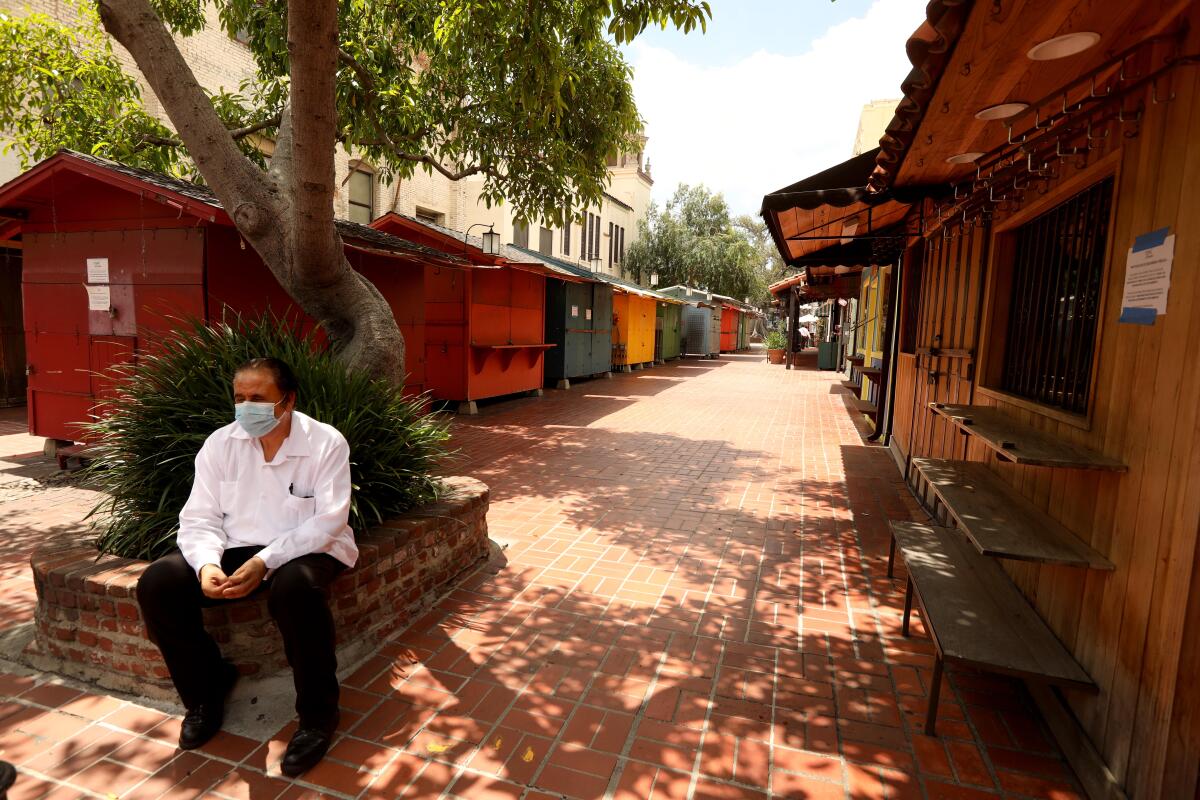

It was a sad sight for Jorge Contreras: rows of blue, yellow and orange puestos, or market stalls, on Olvera Street were shuttered. Nineteenth-century brick buildings that house restaurants, shops and museums were closed, too. La Plaza, typically teeming with people, was empty and quiet.

“This place is not meant to feel sad,” the 55-year-old hat seller said. “It’s supposed to be a place of dance and celebration.”

For nearly a century, Olvera Street merchants — many of them now descendants of original vendors — have sold handcrafted items such as pottery, candles and Mexican folk art. Their survival is intertwined with tourism and cultural events such as Day of the Dead, Blessing of the Animals and Las Posadas, a nine-day Christmas celebration.

But the economic hardship caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is threatening the future of Olvera Street. Tourism has nearly dried up. Stay-at-home orders and other restrictions prevent people from gathering at the plaza and narrow street. Even though restaurants can sell takeout orders, it’s difficult to do so from a marketplace that is enclosed by several streets that require people to park and walk to the eateries.

And now, three months in, more than 70 merchants are asking the city for help. At a recent Los Angeles City Council meeting, Councilman Jose Huizar, whose district includes Olvera Street, introduced a motion that would exempt the merchants from having to pay April and May rents. The City Council is also looking into extending time for commercial tenants to pay back rent.

Olvera Street is part of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, a city department that marks the oldest section of Los Angeles. In addition to the Olvera Street marketplace, it includes La Plaza de Cultura y Artes and several historic buildings.

Valerie Hanley, owner of Casa California and a member of the Olvera Street Merchants Assn., said both efforts proposed by the City Council would help.

“We’re going to really need the city to step in and say we’re going to subsidize the department so us merchants don’t have to until we can get back to normal,” she said.

California’s tepid reopening amid the coronavirus sparked a mix of excitement, confusion and uncertainty.

Arturo Chavez, general manager for El Pueblo de Los Angeles, said the department has an annual budget of $5.6 million, and most of its revenue comes from filming, parking lots, cultural events and rent from merchants.

He said because of the pandemic, the historic district is projected to see a revenue loss for fiscal 2019-2020 of about $1 million.

The marketplace, Chavez said, is in a difficult situation because most vendors sell specialty items and don’t count as essential businesses. The market also relies on tourism and gatherings, which are either prohibited or on the decline.

“We’ve never dealt with a situation like this,” he said. “It’s bad enough that you’re not going to be able to open, and on top of that you have back rent.”

“That’s why they want rent relief,” he added.

Hanley said monthly rent for merchants ranges from $1,000 for small market stalls to $10,000 for larger businesses. She said she’s worried about the future of Olvera Street and isn’t sure how it will operate after the city reopens during the final phase of the stay-at-home order.

“We’re going to be one of the last places to recover, just because we’re one of those areas that rely quite heavily on tourism,” she said. “It makes up about 40% to 70% of our business, and that’s going to be nonexistent for a couple of years.”

The latest maps and charts on the spread of COVID-19 in Los Angeles County, including cases, deaths, closures and restrictions.

Hanley said this has led her to fear that generations of families who have helped preserve the city’s Mexican heritage are on the verge of disappearing unless they get help.

“Ninety years of our legacy gone because of 90 days of hardship,” she said. “We have families that have up to six generations on the street. How do you recover that?”

Hanley’s ties to the area stretch back to 1930, around the time Olvera Street was established as a marketplace. She said her father worked there shining shoes.

“The only time he left the street was to fight in World War II,” Hanley said, adding that he took part in the invasion of Normandy. “His other brothers fought in the Pacific. They all came back alive.”

In the 1960s, her parents opened a business on Olvera Street, selling pottery, religious articles, piñatas and other items. They continue to sell the same types of products.

On a warm Wednesday afternoon, Guillermo Garcia sat under the shade of a tree on Olvera Street, contemplating the future of his restaurant, La Noche Buena, and his shop, Memo’s Place. He also thought about the merchants and employees he has befriended over the decades.

The 61-year-old resident of Silver Lake said he had reopened his restaurant for takeout the previous week because he wanted his employees to make money to pay their rent and bills. He said he has gone from 10 workers to just three, including himself.

“I’m trying,” he said, looking down. “I’m trying to help my workers, but not many people have showed up.”

In an effort to boost business, Garcia joined food delivery apps such as Postmates. Even then, he said, it was slow.

His Mexican restaurant was one of the first to have opened on Olvera Street. Before the coronavirus, the little restaurant was often filled with customers eating tacos and taquitos. Now, the wooden stools are stacked up and the tables crammed inside. At this rate, Garcia said, he could continue for another five months before he will be forced to close.

He said he needs to make about $40,000 each month to be able to pay his rent, employees, bills and other expenses.

Businesses might be able to open their doors again soon — but as they adapt to social distancing as a norm, can they keep on the lights?

Looking around, Garcia said seeing an empty Olvera Street was making him depressed and nostalgic for the days when crowds would swarm the marketplace. He said schoolchildren on tours would run around, and cultural events brought thousands to the street. He also missed the office workers his business depended on during the week.

“I look around and can’t believe what I am seeing,” he said. “It’s empty and sad.”

Garcia was a teen when he arrived in the United States from Durango, Mexico. He had come to work for his grandmother, who opened the restaurant in 1929. He took it over in 1993. He said he took over the shop from a friend four years later.

Financial hardship is not new for Garcia. His businesses have survived economic downturns, including the one after 9/11. Despite how difficult it got, people came to eat and shop on Olvera Street.

But now for the first time, there is nothing.

“I’m trying,” he said. “I don’t know what will happen.”

As the sun began to set over the quiet marketplace, Isabel Caballero, 73, took a bite of a taquito. Her two friends sat next to her. The Pomona resident had grown up around the historic district. Seeing such a desolate place worried her.

“This is our history,” she said. “We can’t lose this place, for the sake of our grandchildren.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.