California schools face ‘devastating’ coronavirus cuts as they struggle to reopen

Even as costs skyrocket in response to the coronavirus crisis, California school districts face major funding cuts that could potentially lead to teacher and staff layoffs and leave some schools struggling to safely reopen campuses in the fall, according to district officials and educators.

The proposed budget hit to schools, about $19 billion split over the next two years, worsens their existing financial challenges and does little to help with pandemic-related costs.

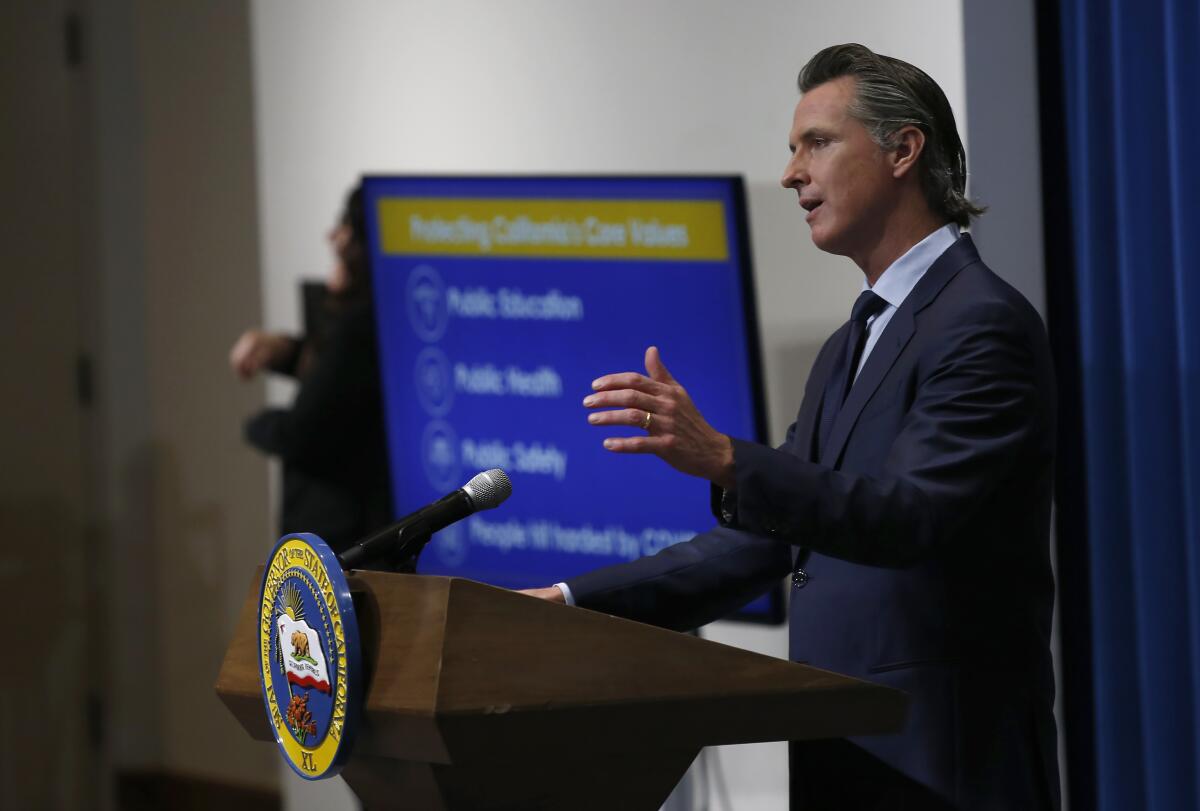

Responding to the revised budget unveiled Thursday by Gov. Gavin Newsom, Xilonin Cruz-Gonzalez, president of the California School Boards Assn., acknowledged that Newsom faced difficult choices in confronting an estimated $54.3-billion state deficit that materialized just as quickly as the coronavirus.

But the share of damage borne by schools is too great, she said.

“This budget would be insufficient in ordinary times, and is less than what is required for most schools to reopen safely during a pandemic,” said Cruz-Gonzalez, who is also a school board member for the Azusa Unified School District, a school system in east Los Angeles County. “And if schools don’t reopen, our economy can’t fully reopen.”

Other school leaders likened the proposed cuts to those during the Great Recession of a decade ago.

“The proposed education cuts for the 2020-21 budget will be devastating at a time when students need more support,” said E. Toby Boyd, president of the influential California Teachers Assn., and “will lead to cuts to vital student programs, educator layoffs, furlough days and pay cuts just like it did during the last recession when we lost 33,000 educators.”

Higher education sustained a concurrent hit, further destabilizing state colleges as they try to plan for fall, uncertain about how many students will return, in person or online, and how classes will be conducted. Earlier this week, the California State University system announced that its fall semester would take place primarily online.

Advocates said the cuts would fall hard on those who can ill afford it.

“All across the state, families, students and communities of color are suffering from the disproportionate effects of the pandemic,” said Elisha Smith Arrillaga, executive director of Education Trust-West, a research and advocacy group.

“Whether it’s struggling with basic needs, financial instability, access to technology, or the undeniable stress parents are experiencing, one thing is clear — our public school and college systems are central to how families and students will recover from this health and economic crisis,” she added.

Still, many advocates and officials gave Newsom credit for a budget plan that could have been much worse for public education.

To ease the sting, Newsom allotted $4.4 billion in emergency federal aid to schools and redirected another $2.3 billion. This money was originally intended to reduce a long-term shortfall in educators’ pensions, a major priority for school districts, but less crucial than addressing the immediate crisis.

Schools also will benefit from Newsom ending some tax credits that will result in $1.8 billion in revenue and higher taxes for some.

In addition, Newsom hoped to rely on deferrals, which delay how soon districts receive money. The delay allows the state to “balance” its budget in the present at the cost of future payments. As a result, districts have to deplete reserves or borrow money to cover their cash flow. But deferrals are better than cuts.

Newsom also approved accounting and funding maneuvers that will preserve higher levels of education funding in future years when the economy eventually recovers.

The strategies won praise from state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond.

“Today’s updated budget proposal includes a variety of measures designed to avoid permanent cuts to education, which otherwise could have lasting impacts on a generation of students,” Thurmond said.

Thurmond also acknowledged there would be no escape from the pain caused by the quickly unfolding recession: “While the measures outlined in today’s proposal are far from what our schools need, we also understand that our state is facing impossible choices under impossible circumstances.”

The cuts include a 10% reduction under a state funding formula that prioritizes aid to English learners and to students from low-income families. Similar reductions will apply to specialized programs such as vocational and teacher training.

The governor also zeroed out ambitious programs announced in January, such as an effort to combat the state’s teacher shortage and expand the quality and quantity of early education.

“Early education escapes drastic cuts,” said Bruce Fuller, an education professor and analyst at UC Berkeley. “But the budget ax falls hard on the wages of preschool teachers, many barely earning a livable wage.”

One item Newsom preserved was an increase to state funding to serve students with disabilities.

“I care deeply about special education and I could not in good conscience be part of dismantling of a commitment we had made,” Newsom said. “We were prepared to make history investments, to invest in our future.... That was January.”

The governor added that cuts to education would be among the first restored if additional federal aid comes through.

The California Teachers Assn. echoed the call for more federal aid — voicing support for legislation sponsored by Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives. The teachers union also suggested that state leaders and voters need to act on their own to raise revenue.

In the meantime, the state colleges will deal with a dizzying reversal in fortunes. In January, Newsom proposed a 5% increase of funds for the University of California and Cal State systems.

Both systems now face 10% cuts without additional federal aid.

At UC, that means a decrease of $338 million; and at CSU, that means a decrease of $398 million. Those are on top of losses sustained due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

UC faced $558 million in unanticipated costs in March alone. At CSU, revenue losses and unanticipated costs for spring 2020 are estimated at $337 million.

“While the fiscal outlook set forth in Governor Newsom’s May budget revision is not unexpected, it is indeed daunting and portends challenging times across the California State University and the entire state,” Chancellor Timothy P. White said in a statement.

The California community colleges also would see roughly a 10% decrease, resulting in fewer classes even as the recession and job losses lead to higher enrollment in the system.

K-12 districts will benefit from about $1.6 billion in direct emergency federal aid. Los Angeles Unified — because of its size and because so many students are members of low-income families — will probably receive about 20% of that funding.

But L.A. schools Supt. Austin Beutner said that funding falls well short of need.

He said he understands the priority for healthcare and directly saving lives. But the imperative for education must quickly follow, he said.

“That child in second grade who doesn’t learn to read now and doesn’t learn to read soon is going to have a different life journey,” Beutner said. “And if she does, we can’t make up for this.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.