MARIPOSA COUNTY, Calif. — Dr. Eric Sergienko was already in his office early last Tuesday when his cellphone pinged with the message he had been both expecting and dreading.

A 23-year-old woman in Mariposa County — the scenic, lightly populated mountain community Sergienko serves as health officer — had tested positive for COVID-19. It was 7:13 a.m., a time that has become seared in Sergienko’s memory the way others mark the birth of a child or the initial tremors of an earthquake.

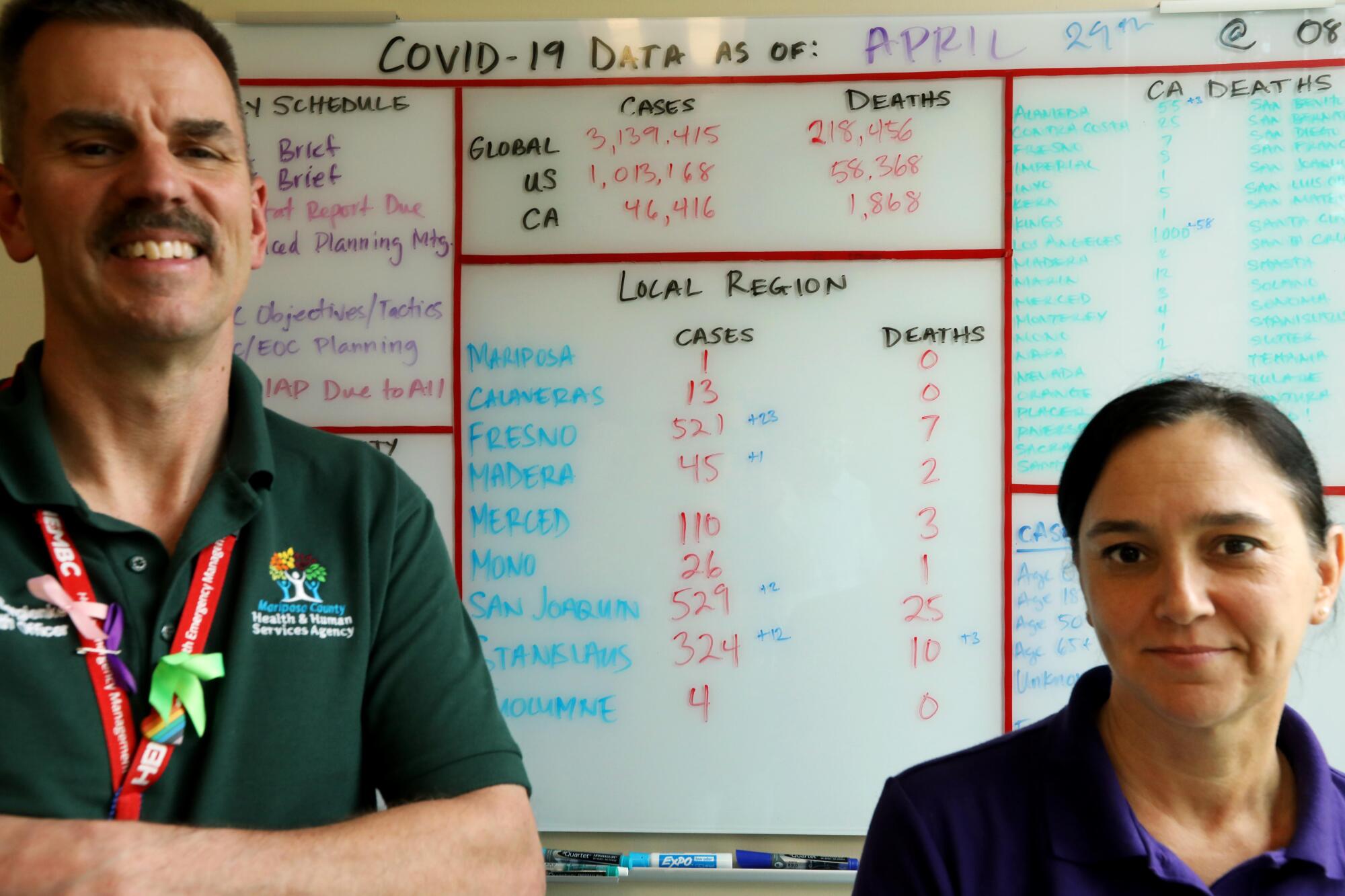

More than 53,000 Californians have tested positive for the novel coronavirus, but in Mariposa County, Tuesday’s result was the first.

Though the case marked the arrival of a potentially deadly pathogen, it also allowed Sergienko to launch a contact-tracing system he had been working on for weeks, one of the final planks of a well-constructed response platform the county has been building for months.

“I like the idea of zero,” Sergienko said hours after the county had lost its perfect record, its initial COVID-19 patient in isolation at home. “But I also like the idea of one because I really do think it’s validation that what you were planning for actually worked.”

If the pandemic’s rapid and deadly spread across the U.S. has exposed government incompetence and lack of preparation in other communities, in Mariposa County the tiny Health and Human Services Agency has offered a textbook example of how to handle a crisis. The county’s first confirmed infection comes at a time of growing protests over stay-at-home orders and demands by other rural California counties that Gov. Gavin Newsom reopen the state.

Mariposa County’s health agency began tracking the virus in December, before many in the country even knew it existed. By mid-January, nearly a week before the first confirmed COVID-19 case in the U.S, a countywide response plan was in place.

And when Gov. Gavin Newsom announced in mid-March that all Californians were being required to stay at home as much as possible, the Mariposa County Sheriff’s Office, utilizing lessons it had learned during the Detwiler fire that swept through the area nearly three years earlier, immediately alerted the county’s 18,000 residents, spread over more than 1,400 square miles, to heed the order.

“Within two hours,” said Joy Shultz, a shopkeeper in Mariposa’s historic city center, “there was no one in town.”

Much of the credit for that goes to Sergienko, a tireless 56-year-old former Navy captain who regularly commuted to his former job in epidemiology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta by running the seven miles from home to work. Like Mariposa County’s own version of leading infectious-disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci, he has loomed large over the local fight against the coronavirus’ spread.

“We were ready for this,” said Chevon Kothari, director of the county’s Health and Human Services Agency. “We worked together as a team during previous disasters, so we already had some of this planning process in place. But in addition, we’ve had the luxury of time to not have cases early on. So we had the ability to plan.”

Sergienko said he first read of COVID-19 on New Year’s Eve, when an international organization that monitors infectious diseases sent an email alert about a strange virus that had emerged in Wuhan, China.

While others ignored the warning, Sergienko alerted Kothari, and two weeks later they informed county supervisors of what could be a danger for a community that sees 4.5 million visitors pass through each year, most on their way to Yosemite National Park, 31 miles to the east.

“The important thing was early recognition. We were already leaning forward and saying, ‘OK, what do we need as a county to be prepared?’” Sergienko said.

“I threw out a bunch of ideas, and people said, ‘Let’s run with this.’”

Mariposa is among California’s smallest counties, and it’s also one of the oldest, dating to 1847 when an agent for John C. Fremont, who would go on to become one of California’s first two senators, mistakenly purchased the desolate Rancho Las Mariposas, then part of Mexico.

A year later, when gold was discovered in Northern California, Mariposa became the southern end of the mother lode and blossomed.

The town has kept that pioneer feel, with the stretch of Highway 140 that splits the center of town resembling a western movie set more than a central business district. Some of the local politicians still wear cowboy hats and bolo ties, but tourism, not gold, drives the economy now.

And that was shut down when Yosemite was closed because of the pandemic in mid-March.

“I like the idea of zero. But I also like the idea of one because I really do think it’s validation that what you were planning for actually worked.”

— Dr. Eric Sergienko, Mariposa County health officer

“It’s a ghost town,” said Joan Gamble from behind the counter at Sierra Mercantile, where protective masks are now for sale alongside Yosemite hoodies and tiny carved black bears. “The park closed, the stores closed. Everything. It’s just something we felt we had to do.”

Credit Sergienko for that too. Social distancing wasn’t a difficult sell in a county where the minimum parcel size in rural areas is 5 acres, but he also won people over on the need to wear face coverings and repeatedly wash their hands.

So when the order came to close down business and schools, most people were already on board.

“They are pretty lockstep in [that] they don’t want to open up too soon,” Travis Medlock, who operates a ramen restaurant out of a closed 1950s-style diner, said of the business community. “While the businesses don’t like it, they completely understand.

“They are very concerned of opening the park back up. That is just going to bring the Bay Area, the valley, L.A. up here. We’ve been locked down pretty secure [but] as soon as they open the floodgates there, we’re concerned it’s going to open the floodgates here.”

Medlock said the county has had his back in other ways too, sending office staffers for takeout meals to help his fledgling restaurant stay afloat.

Sergienko, whose quirky, slightly nerdy personality is as infectious as the coronavirus he’s battling, likes to refer to protective bubbles. A bubble can cover a single person or an entire community, but if anything pierces that bubble, it breaks and leaves everyone inside exposed.

That Mariposa’s bubble was strong was evidenced by the fact it is surrounded on all sides by counties with more than 200 cases and half a dozen deaths combined.

Minutes after that bubble finally burst Tuesday morning, Sergienko moved to patch the hole, dispatching a contact-tracing team including two health professionals and a sheriff’s detective as well as a probation officer and an investigator with the district attorney’s office.

They began searching for anyone who may have come in contact with a Mariposa resident who tested positive in a hospital in neighboring Madera County after traveling internationally.

“We really recognized early on we needed to build up a team that was beyond what we had in public health capacity to do,” Kothari said of contact tracing, a key tool in halting the spread of infectious disease. “Who better than people who are used to investigating? So probation officers, D.A. investigators all got trained in contact tracing pretty early.

“Now a lot of counties are emulating that, a lot of counties are pulling in their law enforcement partners to help with that. They’re really good at contact tracing.”

Within hours, 25 people had been identified. When half of those tested positive over the next three days, Sergienko’s team already had them in quarantine, protecting the rest of the community and validating his plan.

“We know where everyone is. So we’ve nipped off that bud of transmission,” said Sergienko, whose county now has 13 confirmed cases. “The team was ready for it. The team stepped up and did what they needed to do.”

With COVID-19 now present in the community, Mariposa County is shoring up other defensive measures. Thursday it opened a testing center in a middle school gym with a goal of administering 132 free tests a day, about five times the recommended number for a population of 18,000.

Another protective measure requires county employees to enter vital information such as body temperature and other symptoms into a phone app each morning, giving the health department more data points to track. Kothari hopes to have all county businesses using the app when the stay-at-home order is lifted.

When that happens, and Mariposa’s main roads again become clogged with summer vacationers headed for Yosemite or weekend visitors taking in the scenery, that will be the next test for the protective bubble Kothari and Sergienko have designed.

Their team is working on a plan for that too.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.