Protesters rally in Orange County to denounce Newsom’s beach closure

On the seventh Saturday of the state’s stay-at-home order, the division over mandatory closures widened, and the flashpoint in Southern California was once again the beaches of Orange County.

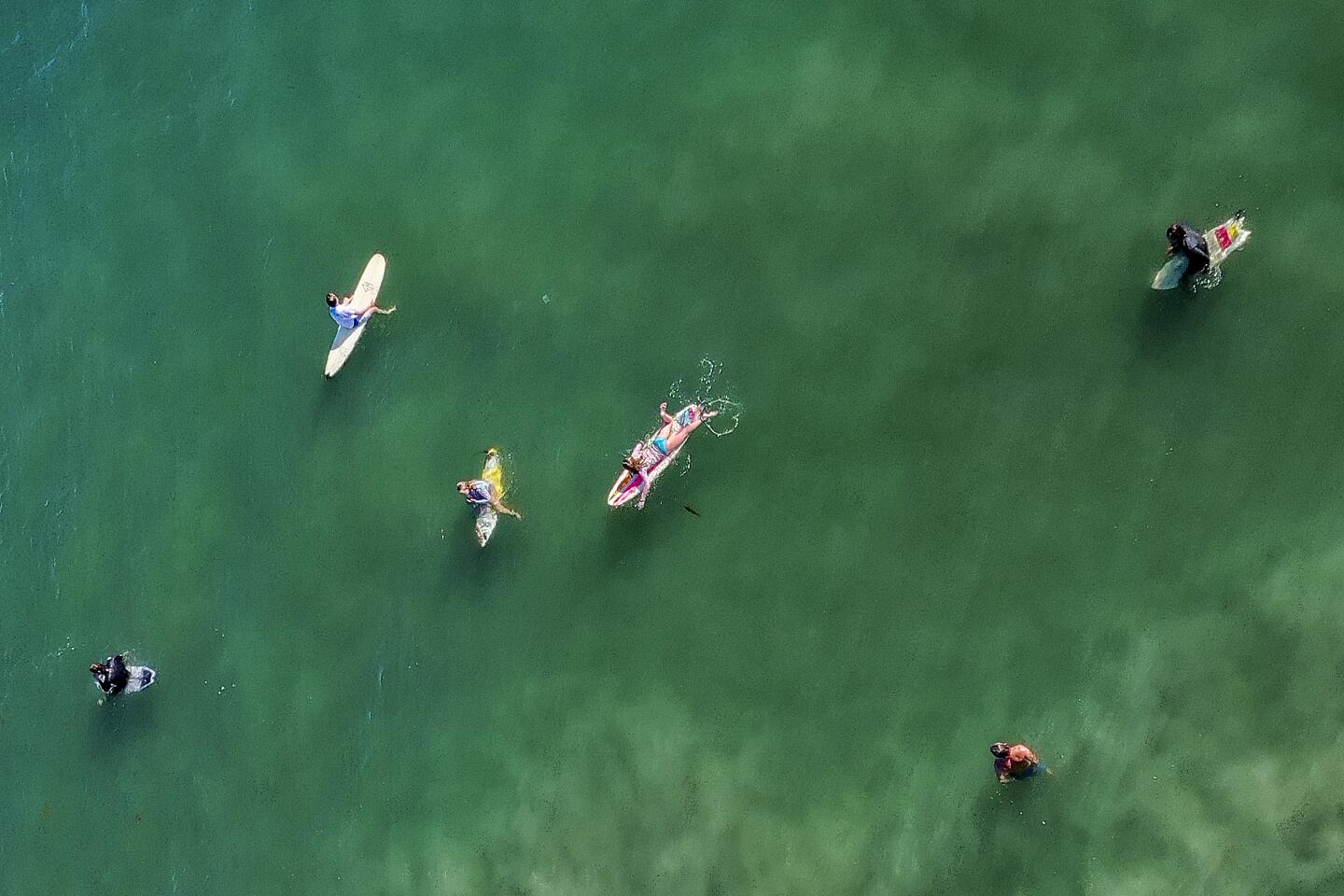

Surfers hopped fences. Walkers strolled with their dogs, and parking lots became impromptu Chautauquas to debate policy and voice opinion.

The actions are in defiance of the orders issued Thursday by Gov. Gavin Newsom calling for a “hard close” of all state and local beaches, a mandate that singled out the sandy stretches of Orange County for last week’s crowds who were seeking relief from an early heatwave.

In a letter to the Orange County Board of Supervisors, the governor’s office of emergency services stated that the “high concentration of beach visitors in close proximity ... threaten the health of both beach visitors and community members.”

“In response, our State Department of Parks and Recreation is shifting to full closure of all Orange County State Beaches on a temporary basis.”

The restriction applied as well to beaches operated by local governments in Orange County.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom is facing growing impatience with stay-at-home orders meant to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, and a legal showdown looms over his closure of Orange County beaches.

At the Huntington Beach pier — as a light morning fog lifted — about 50 protesters gathered to pick up where they had left off on Friday. The turnout was light, but the rhetoric was just as passionate.

“The orders of Newsom are not constitutional, and they are not effective in any way,” said Kyle Richardson, who had designed a poster the night before.

Waving to passing cars on Pacific Coast Highway, Richardson portrayed Gov. Gavin Newsom in a Nazi uniform beneath a red flag and a swastika. “Obey the Fuhrer,” it read the script. Opposite were a hand-drawn star, surfboard and the words, “Come and Get it,” a reference to the first battle of the Texas Revolution in 1835.

“There isn’t a COVID-19 problem in Orange County,” said Richardson, 35. “This punitive measure of shutting down beaches and keeping everything closed is not accomplishing anything.”

County health officials on Saturday announced two new coronavirus-related fatalities, bringing the death toll to 52. The county also reported 99 new cases, with the total number standing at 2,636.

At the north side of the Newport Beach pier, the parking lot was crowded with people wanting to get out onto the sand. American flags competed with red MAGA hats.

At noon, the gathering — numbering nearly 70 — started walking across the beach to the ocean. Newport Beach police officers advised them to turn back, and a helicopter from the Orange County Sheriff Department flew over, announcing the closure over a loudspeaker.

As a few people went into the water, lifeguards in a boat just beyond the surf line informed them that the beach was closed.

Eventually the crowd dispersed, but a half dozen stood their ground and debated their case with police officers not far from the water. Bill Beukers was among them. He and his wife had driven down from Lancaster, and uncertain how the conversation would go, she filmed the exchange while the couple’s children bodysurfed.

Beukers, 48, said afterward that he was willing to get arrested and that the discussion had less to do with the beach than the constitutionality of the closure.

“Where do we go from here?” he recalled asking the officers. “What side of history do you want to be on? Someone has to stand their ground. We’re on a slippery slope, and we might end up where we might not want to be.”

He cited the 2nd Amendment and Rosa Parks, and in the end, the parties shook hands and the police departed.

In Huntington Beach, law enforcement was also trying to interpret and enforce the closures. About two police cruisers blocked the entrance to a bike path. A police motorcycle and a SUV were parked at the base of the pier, where yellow caution tape had been strung.

The day before, Huntington Beach resident Pete Hamborg stood on the sand with a garden hoe, carving out the letters to a vaguely obscene insult directed to the governor.

While not participating in the Huntington Beach demonstration, Hamborg sympathizes with the protesters. He believes that the beach closure creates a dangerous precedent in the event there are additional outbreaks or a new pandemic.

Hamborg argues that public health compliance is necessary. “This isn’t the first pandemic and will not be the last,” he said. “The virus can mutate, or someone can eat a bat or an aardvark and hop on an airliner. It will happen again.”

But he worries that unpopular actions like the beach closure will exhaust the public tolerance and good will.

“If leadership is unreasonable,” he said, “there will be a cost to be paid in the future because people will not put up with it. They will not have the attitude to comply as they have already. We can’t overreact because this might not be the only time we need to react. We need to have good will in the bank.”

Trying to get a handle on how California is reopening and what it means for you? Our guide includes updates and tips for remaining healthy and sane.

Hamborg, who recently retired from the Orange County Fire Authority, takes his time on the beach seriously. He walks the strand, surfs and paddle-boards. Since the stay-at-home orders were issued in March, he tries to get down to the beach at least once a day.

“I have an addiction,” he says. “I need to go to a 12-step program, and it’s called 12-steps in the sand.”

Residents of Huntington Beach, like Hamborg, believe that Gov. Newsom doesn’t understand their community and singled it out for more reasons than just the pandemic.

“I was waiting for the governor to put his foot on our neck,” Hamborg said. “And this seems like a political power play because Huntington Beach hasn’t been cooperative with him.”

Chuck Brewer, 65, walks the beach every day, often joining his friends — “we call ourselves the Wally Boys” — on the wall at the pavilion. He believes the closure was an overreach. “It’s kinda like martial law,” he says.

Brewer believes Newsom is reacting over the 2018 decision by the Orange County Board of Supervisors to join the Trump administration’s federal lawsuit against California over its immigration laws.

“My personal opinion is that the governor is upset with Orange County because it didn’t go along with the state’s amnesty or sanctuary polities, and this is his way to pay back,” Brewer said.

In arguing against the closure, Brewer would like to see data that support the decision. From his perspective, the sunshine and ocean air are a good way of keeping the coronavirus away.

Later at the demonstration, Richardson decided it was time to hit the water. The sun was out, and the day was beautiful.

Waving off the police officers who warned him that going on the beach would be a misdemeanor, Richardson continued across the empty stretch of sand.

He put down his signs and in red, white and blue board shorts, stepped into the surf. Once beyond the breakers, he looked back and saw no one on the beach, a rarity.

“It was so glorious,” he said afterward. “It could not have been more perfect: cool enough to be refreshing and not too cold. It was a perfect Orange County Day.”

Back on shore, as the protesters made plans to head to Laguna Beach to continue their action, Richardson was ready to bail.

“I’m tired and sunburned,” he said. “I think I’ll go grab some tacos.”

Times staff photographers Wally Skalij, Luis Sinco and Allen J. Schaben contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.