Column: These researchers aren’t waiting for COVID-19 answers, they’re finding them

In Las Vegas, an ER doctor infected by COVID-19 was critically ill and getting worse, and his chest X-ray gave him a fright.

“I looked at it and thought, ‘My God, I’m gonna die.’”

But a call went out to a California pathologist, and soon a medical courier was driving from Santa Maria to Nevada with a container of frozen plasma packed in a cooler box.

Meanwhile, as the COVID-19 death toll rose, with first responders and healthcare workers among the victims, UCLA epidemiologist Anne Rimoin was not about to wait around for government support for something she thought could help crack some of the mysteries of the coronavirus and save lives.

So she launched the effort on her own.

These two stories, one in Las Vegas and one in Los Angeles, are not directly related but there’s an obvious connection.

We’re in a scary, uncertain place at the moment, and may be for quite a while. But it’s comforting to know that when it comes to the science of developing vaccines, and valiant efforts to keep people alive in the meantime, the race to beat the virus is being waged on many fronts.

Let me start with the UCLA effort and then get back to the Las Vegas doctor who feared he might not pull through.

Before I spoke to Dr. Rimoin, The Times had reported that 3,100 healthcare workers in California had tested positive for COVID-19 in California. Ten of them had died.

“We have a moral duty” to protect those workers, Rimoin said. “The first thing about people on the front lines is that they’re terrified, they’re living in hotels, they’re making out wills, they’re living in garages not knowing about their status,” and not wanting to expose loved ones, she added.

Rimoin, an infectious disease expert who developed a healthcare worker monitoring program in Democratic Republic of the Congo, told me she wanted to replicate that model here. Rather than write grant proposals and wait months to hear back, she went to a trusted colleague at UCLA — Dr. Grace Aldrovandi, a virology immunology expert who oversees 200 research labs in 18 countries — and together they started the UCLA COVID-19 Rapid Response Initiative.

The effort will try to determine how many workers test positive without symptoms, look for signs of pre-symptomatic infection, seek to better understand how the body builds immunity and how durable that protection is, examine the prevalence of reinfection, begin building a plasma bank to provide antibody serum to patients, and aid efforts to develop vaccines and other therapies.

“The body sees a pathogen and rallies up an army. It makes antibodies that go and neutralize a virus,” Aldrovandi said, and the research is about developing an arsenal of ammunition.

Rimoin and Aldrovandi tapped “every resource we had between us” for start-up money. Donations came from — among others — Hollywood A-listers Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson, both of whom are COVID-19 survivors.

In its first phase, the program has already enrolled several hundred UCLA healthcare workers, including doctors, nurses, medical aides and room attendants, for repeated viral screening that includes nasal swabs, saliva samples and blood draws.

They’re hoping to increase that number to 4,000 workers, the doctors said. And then, if they can raise more money, they’d like to add 4,000 first responders to the study, along with 4,000 more healthcare workers from community hospitals.

“I’m a big fan of this and it’s going to give us some information we don’t currently have,” said Dr. Clayton Kazan, medical director of the L.A. County Fire Department, which is prepared to have a few thousand employees participate in the research as the UCLA effort ramps up.

The county fire department has already had 17 employees test positive, Kazan said. He said that despite strict personal protection requirements for paramedics and other employees, many firefighters consider themselves invincible, and he worries that, as time passes, they will start being more lax, on the theory that they have probably already been exposed, built immunity to COVID-19 and are now safe.

Regular screening, he said, will make it easier to quickly isolate infected employees, limit the spread of the virus and remind first responders they they can’t relax self-protection protocols.

Let me get back now to the story of Dr. Garrett Emery, the ER physician who took ill in Las Vegas.

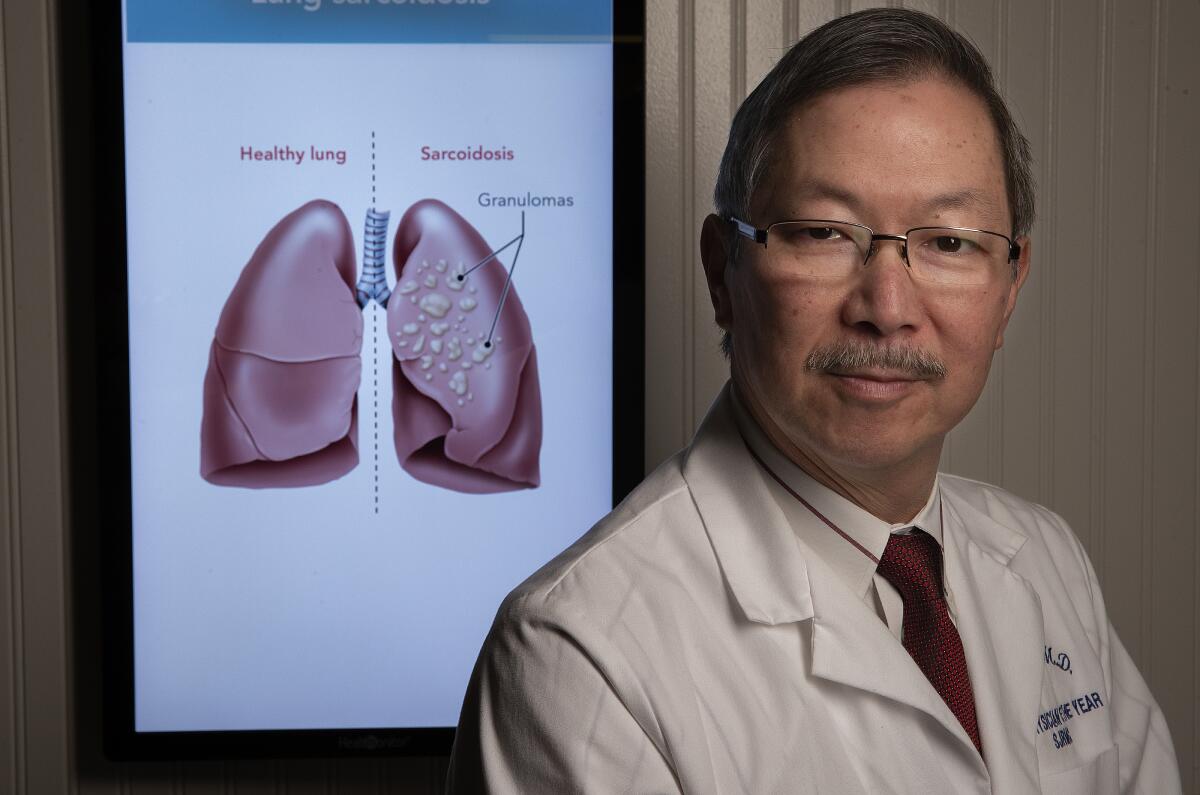

I heard about Emery from Dr. George Yu, the Camarillo lung specialist I wrote about two weeks ago when he recruited a convalescing COVID-19 patient to donate plasma that was given to two critical COVID-19 patients. The first recipient died; the second, a Santa Maria resident, has come back from the brink of death but is still hospitalized.

“I began feeling ill the first week of April,” Dr. Emery told me by phone. He’s a traveling ER doctor but lives in Las Vegas.

“I had difficulty breathing, a cough … some unusual sensations throughout my body and a burning in my chest. It almost felt like I could feel my lungs being damaged,” said Emery, who also had a horrible metallic taste in his mouth.

A doctor prescribed hydroxychloroquine, the antimalarial drug that’s been in the news as a possible cure with potentially harmful side effects, and Zithromax, an antibiotic. Emery only got worse. He has an oximeter, the finger clip that measures the level of oxygen in the blood, and saw that he was in the low 80s.

“It should be in the high 90s,” Emery said. “My respiratory rate increased, I was breathing very quickly and at that point I realized, ‘I gotta go to the hospital.’”

That was on the morning of April 16. His lab work was not great and a chest X-ray showed moderate lung congestion. He wanted to go home and nurse himself, but kept getting worse, to the point he feared he might have to be intubated and put on a ventilator.

Doctors tried high-flow oxygen for a day, then took another chest X-ray.

“It was one of the worst X-rays I have seen with this disease. Both my lungs were filled with gunk,” Emery said.

He continued to deteriorate, and his doctors recommended an infusion of convalescent plasma. One of them called Marissa Li, a California-based pathologist with Vitalant, a nonprofit blood donation company that’s accepting and distributing plasma donations. Li located some plasma that matched Emery’s blood type at Marian Regional Medical Center in Santa Maria.

A courier drove the plasma to Las Vegas on April 19 and the infusion began around midnight.

“So the next day was the 20th and I was still bad, but in the afternoon things started to improve and I was requiring less oxygen,” Emery said.

“On the morning of the 21st, 36 hours after the infusion, I felt 30% to 40% better. … I had no fever for the first day in two weeks. … I got my taste back and was able to get the oxygen turned all the way off.”

When someone recovers from COVID-19, it’s not clear why they improved, or whether they would have gotten better without medication. But Emery said he strongly believes the serum did the trick for him, and a phone conversation with Dr. Yu made him all the more certain.

Yu told me he studied Emery’s lab work in collaboration with Emery’s doctors in Nevada. He said Emery was in the midst of a cytokine storm, an often fatal condition in which the body attacks its own cells.

“As a lung specialist and critical-care specialist, I’ve never seen a turnaround like this,” Yu said. “I’ve seen many cytokine storms, but I’ve never seen one progress to this stage and then make a U-turn.”

Emery went home a few days after receiving the infusion and told me he plans to return to work on Friday.

So here’s hoping he continues to soldier on, that the UCLA researchers find ways to better understand what we’re up against, and that we continue to fight back with everything we have.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.