O.C. learning center comes to the rescue for panicked parents during pandemic

Emeteria Hernandez walked through the empty supermarket aisles, hunting for food, hand sanitizer and Clorox wipes for her family.

Nothing.

The month-old memory still brings fresh tears to her eyes.

“I thought the world was going to end,” the 41-year-old cook said in Spanish. “And I didn’t have food for my [three] kids.”

That afternoon, she received a call from Myrna Zornoza, an educator at the Shalimar Learning Center, the Costa Mesa-based founding facility of the not-for-profit organization Think Together.

“What do you need?” asked “Ms. Myrna,” as Hernandez affectionately calls her, after two years of attending Think Together’s parenting classes while her son Jeremy went to after-school teen classes.

Soon, Hernandez received the first bins from Think Together, filled with food, sanitizer and soap. The next week, more food came. Then more food, soap, toothpaste and $100 gift cards.

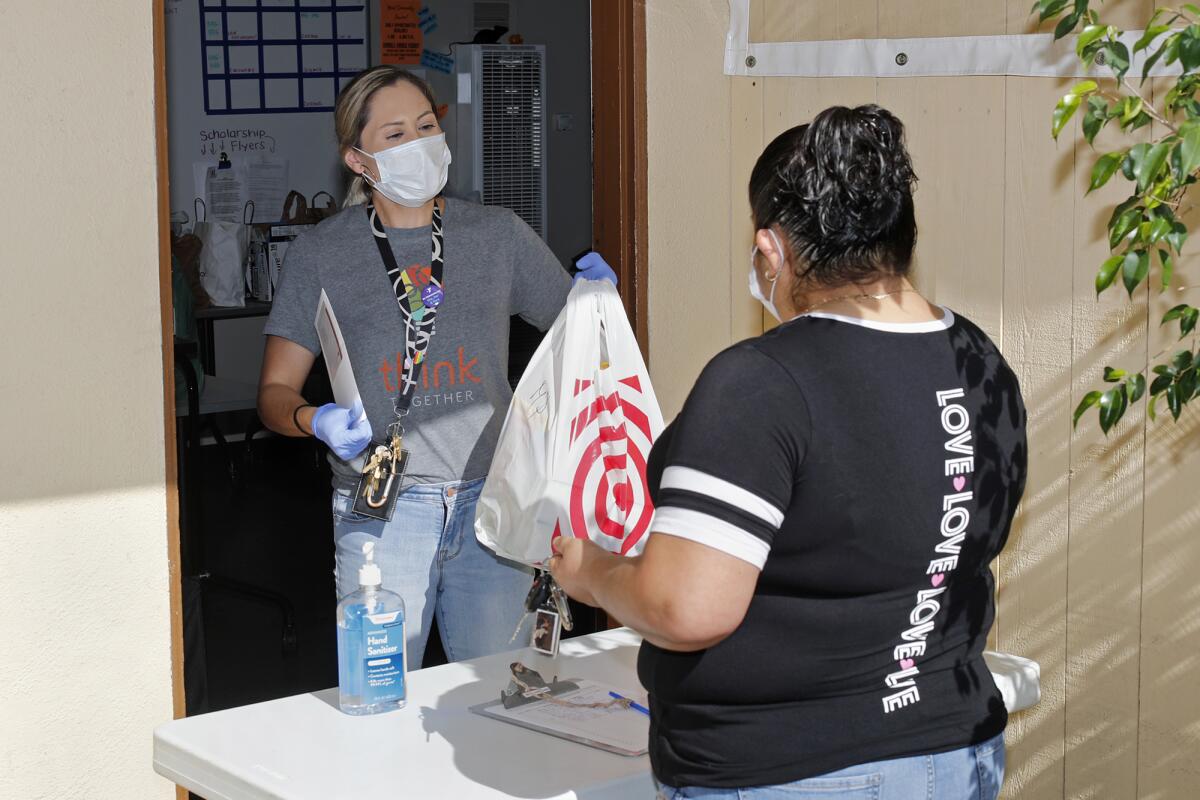

In the age of the coronavirus, organizations that offered one kind of service — such as Think Together’s educational programs after school and during the summer — have found themselves pivoting to serve the ever-changing requests of an increasingly needy population.

The Shalimar Learning Center had just hit 25 years of offering educational services to about 120 families in its predominantly Latino and low-income neighborhood in Westside Costa Mesa, called Shalimar. The center, which operates out of an apartment in Shalimar, was the go-to after-school place for nearly 250 neighborhood children whose parents worked multiple jobs. At various points, it also provided translation services for families, as well as all-around academic support and college and career guidance.

But then the coronavirus blew through, decimating the jobs of 100% of the center’s participating parents.

“Just all of a sudden, boom, they’re done,” said Randy Barth, Think Together’s chief executive.

At Shalimar, he said, many of the parents were hourly workers — housekeepers, gardeners, restaurant and hotel workers — without severance benefits. Some were undocumented and, at the time, ineligible for federal stimulus aid.

Without jobs or with severely reduced hours, parents didn’t have enough gas to drive to their children’s schools to pick up meals. Cell phone and internet bills went unpaid — and with them, the ability to participate in online learning.

Hernandez went from cooking five days a week at a pizzeria in Costa Mesa to just nine hours a week. Her husband was let go from his day job cooking at a restaurant in Newport Beach. The family began relying solely on his evening job, which brought in 25 paid hours a week — and on Think Together.

“What everybody was talking about was, ‘We’re so scared, what are we going to do?’” said Melissa Arambula, 35, family and community coordinator for Shalimar Learning Center. “A lot of that came from having food on their table. They were all losing their jobs. It was just a lot.

“We immediately started transition,” she added. “Academic support can wait; we need to meet basic needs right now.”

The center is accepting donations for basic food items, such as milk, eggs, bread and tortillas, as well as nonperishable items. It has also set up a relief fund to finance the $100 debit cards that families get every week to help cover basic necessities such as groceries or gas. Individual giving has ticked upward, according to Darcie Schott, Think Together’s director of philanthropy, as have company matching donations.

“[Shalimar] does represent some of our lower-income families and students, yet they’re very bright students, and that community is in the shadows of some of the wealthiest communities and neighborhoods in Southern California,” Schott said. “There’s recognition of that and ownership and accountability.”

Now that the initial shock has passed, the center continues to expand its offerings to help families in other ways, such as supplying supplies for STEM and arts lessons for home learning, flushing out a distance-learning after-school option and translating information from the city and district schools.

Perhaps now more than ever, Hernandez draws on Zornoza’s parenting lessons.

“Every time I feel like I’m going to fall into depression, I remember all the words that they’ve taught me,” she said. “To always try and stay positive. To be strong in every moment. To try to make it through the difficult times that come our way in life.”

Pinho writes for Times Community News.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.