The natural air conditioner created some 13 million years ago with the formation of Santa Monica Bay has helped charm and cool Angelenos from the time people first inhabited this land. The chance to enjoy ocean breezes, and perhaps a swim, seemed like a Los Angeles birthright.

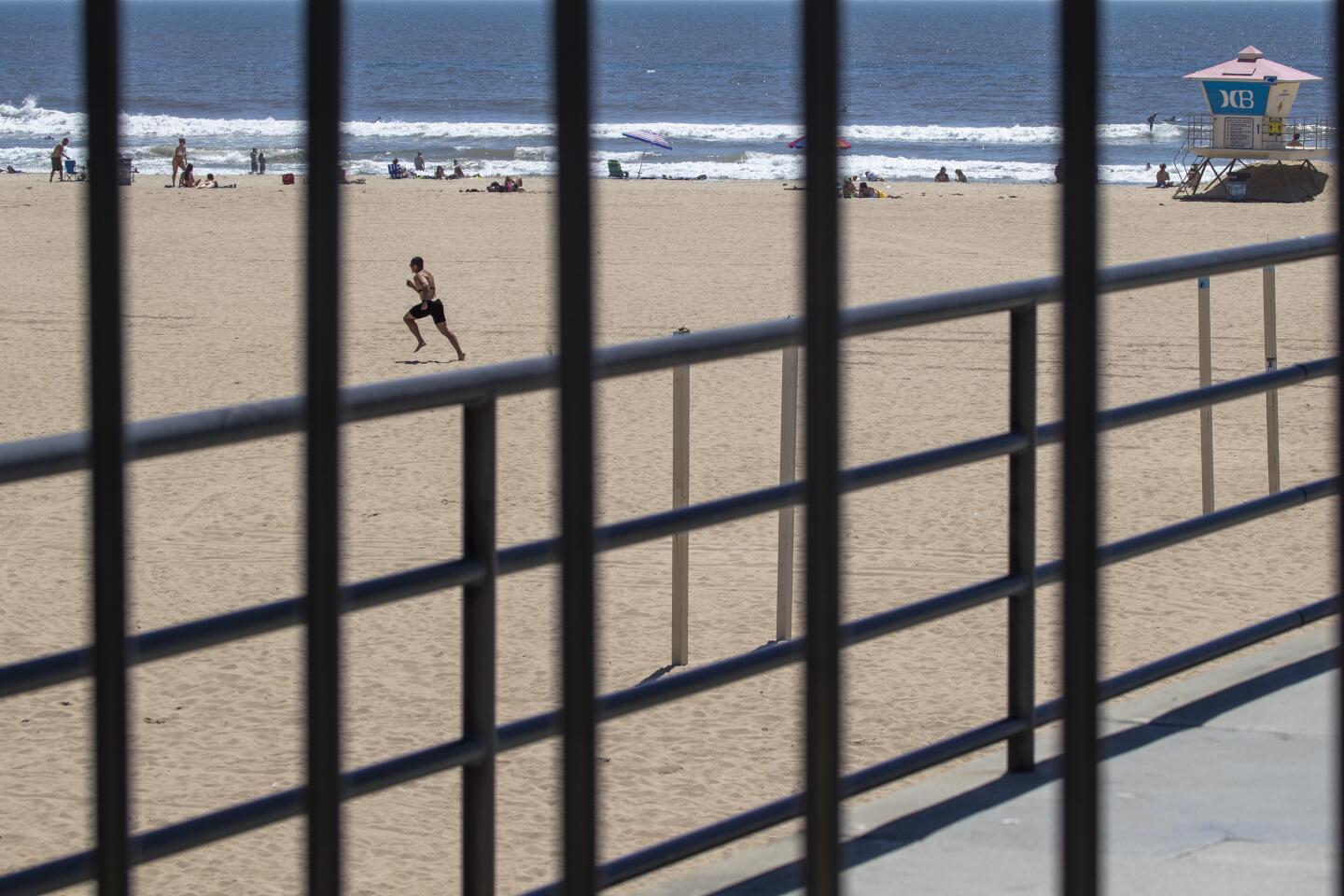

But the coronavirus pandemic has upended many truths of earlier eras. Now the people of Los Angeles will enter their sixth week under a stay-at-home order, facing a weekend of 90-degree-plus temperatures, with all 72 miles of the Los Angeles County coast closed to one and all.

The people appear prepared to abide. At least most of them. At least for now.

But the shutdown of beaches from Malibu to the Orange County border is serving as a reminder of privileges that the county’s 10 million residents may have taken for granted, of the friction created when those privileges disappear and of the unequal access citizens have to the ocean and other open spaces.

Barbara Ferrer, director of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, has said repeatedly that the beaches must remain closed to prevent an overflow of visitors who might be carrying the potentially deadly SARS-CoV-2 virus. She has asked L.A. residents not to crowd beaches in neighboring Ventura and Orange counties.

“We have high rates of illness and a lot of people in our county who are dying. We know it’s best right now for us Angelenos to stay home, or stay outside [in] your own yard or your own neighborhood,” Ferrer told the media Wednesday. To do otherwise, she said, would increase the risk of bringing the infection to L.A. “And we absolutely don’t need that.”

PHOTOS: Coronavirus and beaches: What’s open and what’s closed

Public officials and those patrolling the beaches say that compliance with the shutdown has been high, with only about half a dozen people cited in more than a month for breaking the county beach ban. Politicians including L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti, the county Board of Supervisors and Gov. Gavin Newsom cite polls showing public support for hunkering down longer to slow the coronavirus.

But that feeling will not hold forever. And a vocal minority already is bridling to get back to something close to normal life, which includes soaking up the beach sun and diving into the invigorating Pacific Ocean. They have registered their impatience in a poll taken by Surfer magazine, in a petition to reopen Manhattan Beach and in other forms of protest.

“There is no logical or defensible reason to disallow access to the ocean, provided we maintain responsible spacing, which is essentially guaranteed by Mother Nature,” wrote Andrew Mactavish, one of more than 4,100 people to sign a Change.org petition to reopen Manhattan Beach. “This is a ridiculous publicity stunt on the part of paranoid and apparently ignorant public officials.”

Justis Brown, another petition signatory, added: “Surfing is not a crime.” Many of those signing the petition in one of L.A.’s wealthiest communities proposed allowing locals, alone, to have access to the shore.

In late March, a surfer in Manhattan Beach was one of the rare scofflaws, fined $1,000 for ignoring repeated warnings to exit the surf.

Readers of Surfer magazine had a wide range of opinions about the closures too, with 72% of 6,000 in an Instagram survey telling the venerable magazine they did not think surfing should be “restricted at this time.”

A reader identifying himself as “Purple Grapes” commented: “This situation is ridiculous. There is not one documented case of beach- or surf-spread COVID …Let us surf, it’s what we do.”

Opinion in the lineup has been far from unanimous, however. BlueChefHat said on the Surfer comment board: “The critical problem is humans who believe as individuals their rights are more important than the collective health of the planet. Generations before have been asked to go to war. We’ve been asked to watch Netflix for a few weeks.”

Surfer Editor in Chief Todd Prodanovich said he cannot recall an issue that has become this divisive in his 10 years at the magazine. “I’ve never experienced anything quite like this,” he said.

He agreed in a note to readers that, on many beaches, social distancing and surfing appear compatible. But not at the most crowded spots such as Malibu, the landmark break just up the coast from the city’s historic pier.

One of the surfing community’s most prominent organizations, Surfrider Foundation, said it shifted its messaging as the science and public health information evolved. It first advised social distancing, before calling on its members to just “#StayHomeShredLater.”

“Californians should’ve erred on the side of caution quite a while back, and we didn’t,” Jennifer Savage, Surfrider’s policy manager in California, said. “So it makes a lot of sense that we should collectively choose to err on the side of caution going forward, so that we can get through all of this faster, together.”

Savage said many folks have supported this new message but acknowledged the difficult shift in consciousness this requires for surfers and others.

With Los Angeles beaches closed and potential record temperatures expected beginning Friday, one politician in neighboring Orange County suggested shutting beaches there, to stave off a flood of outsiders, including potential COVID-19 carriers.

Supervisor Lisa Bartlett said Orange County had an obligation to protect local residents. “When you take a look at the folks that are coming down,” she said, “they’re not only not adhering to safer-at-home policies in their own communities, they’re not even staying in their own counties.”

These are some of the unusual new scenes across the Southland during the coronavirus outbreak.

Bartlett added that a shutdown would have to apply to everyone because of the California Coastal Act, which declares that access to the beach is a right of every Californian. But Bartlett got no support for her full shutdown proposal.

The Coastal Commission, the gatekeeper of California’s beach access law, has been allowing cities and counties to make the call on whether beaches should be temporarily closed — citing the emergency need to protect public health and safety. But Jack Ainsworth, the commission’s executive director, reminded local officials in a March 24 letter that access limitations were not absolute and that “the coast belongs to all.”

Many point to the unequal impact of the closures, given that residents in some coastal communities have greater access to parks, beaches and hiking trails while more working-class (and often less white) communities inland swelter in more confined spaces.

Lucas Zucker, who has advocated for greater environmental justice on the Central Coast, noted that the people who are still able to go to the beach are primarily those who can afford to live within walking or biking distance. As the days get hotter, he said, stay-at-home orders will become even more difficult for those who are trapped in inland neighborhoods, near freeways or in industrial areas.

“Some families are feeling like ‘Wow, this is the first time I don’t have a chance to go outside and get some fresh air,’ “ said Zucker, policy director for the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE). “But for many communities, they’ve been living with that lack of access to open space, clean air and exercise for a very long time.”

Still, even coastal residents attuned to such inequities can find it hard to accept that they can’t, for instance, go in the ocean when they don’t see crowds at their local beach. They call for compromise measures, like those enacted Wednesday in Ventura.

That city agreed to allow people to use the city’s beaches, pier, promenade and parks as long as they keep their distance from one another and remain on the move. Visitors will be allowed to walk up and down the city’s pier or on the sand but not be allowed to sit on the beach or stand against the pier’s railing to fish.

While there has been no conclusive research, it’s believed the virus would not survive well in chlorine and it’s likely vulnerable to saltwater as well, said Mark Gold, deputy secretary for coast and ocean policy under Newsom. The bigger risk is people congregating onshore, Gold said.

“We all want to go to the beach and enjoy this great weather,” Gold said, “but we have come too far together to stop doing what has been working.”

In Los Angeles, Mayor Garcetti seconded the county’s Ferrer in urging residents to continue to stay close to home and not crowd into other counties that are gradually opening beaches.

“We need to continue to look back and be able to say that we got out of this safer, with fewer deaths, and sooner because we stayed at home,” he said.

Times staff writers Priscella Vega and Luke Money contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.