SOLVANG, Calif. — With his wire-rim glasses, burly build and shock of alabaster hair tucked into a bike helmet, Chuck Stacy looked a little like Santa Claus on vacation as he pedaled through Solvang’s quaint business district last week.

He was leisurely riding down the center of an empty street in this California tourist haven that would be clogged with traffic under normal circumstances.

But these aren’t normal times.

With much of the country under stay-at-home orders to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus the Danish-settled village, whose windmills and half-timbered architecture draws more than 1½ million visitors a year, is a virtual ghost town.

“I’ve never seen it like this,” said Stacy, a retired Episcopal preacher who has spent 53 of his 72 years in Solvang.

A couple of blocks away Thomas Birkholm keeps his Danish bakery going by preparing takeout orders with a staff made up largely of family after laying off 16 employees.

“Every day it’s like Christmas morning coming in here,” Birkholm said. “The streets are empty and everything’s closed.”

This is the equivalent of an economic earthquake for this tiny town of nearly 6,000 people nestled in the Santa Ynez Valley wine country, about a half hour north of Santa Barbara. Tourists are the engine of an economy than generates nearly $200 million in activity a year. Hundreds in Solvang and the surrounding bedroom communities have already lost their jobs while the city is losing $500,000 in tax revenue a month.

“That’s a lot of money to a town this size,” said Andrew Moore, whose wine-tasting room has shut down. “It’s a lot of money to a town of any size.”

On a typical spring weekend just a handful of the city’s 847 hotel rooms would be empty and the lines to get into the wine-tasting rooms and restaurants would be long. This weekend just a handful of the city’s hotels were even open and the longest line was outside Bethania Lutheran Church, where people queued up for food donations.

Solvang began to feel the effects of the coronavirus pandemic March 15, when the Chumash Casino Resort in neighboring Santa Ynez closed. Four days later the rest of the state shut down too, with Gov. Gavin Newsom ordering all nonessential businesses to shut down.

For a city that has endured floods, fires and economic downturns, the governor’s declaration was another painful blow.

“This is just on a totally different scale,” said Mayor Ryan Toussaint, who has lived in the city all his life. “There is no playbook for this.”

Toussaint, 33, said he is asked every day when things will go back to the way they were before, a question he can’t answer. But the new normal, he acknowledges, is not sustainable.

“People are kind of getting frustrated,” he said. “How long can they stay cooped up?”

Solvang’s majestic festival theater is among the city’s many shuttered businesses, the nonprofit having already postponed most of its summer season. The Rancheros Visitadores, a procession of 750 cowboys whose numbers once included Ronald Reagan, Clark Gable and Walt Disney, have called off next month’s fundraising ride into town for the first time in 89 years.

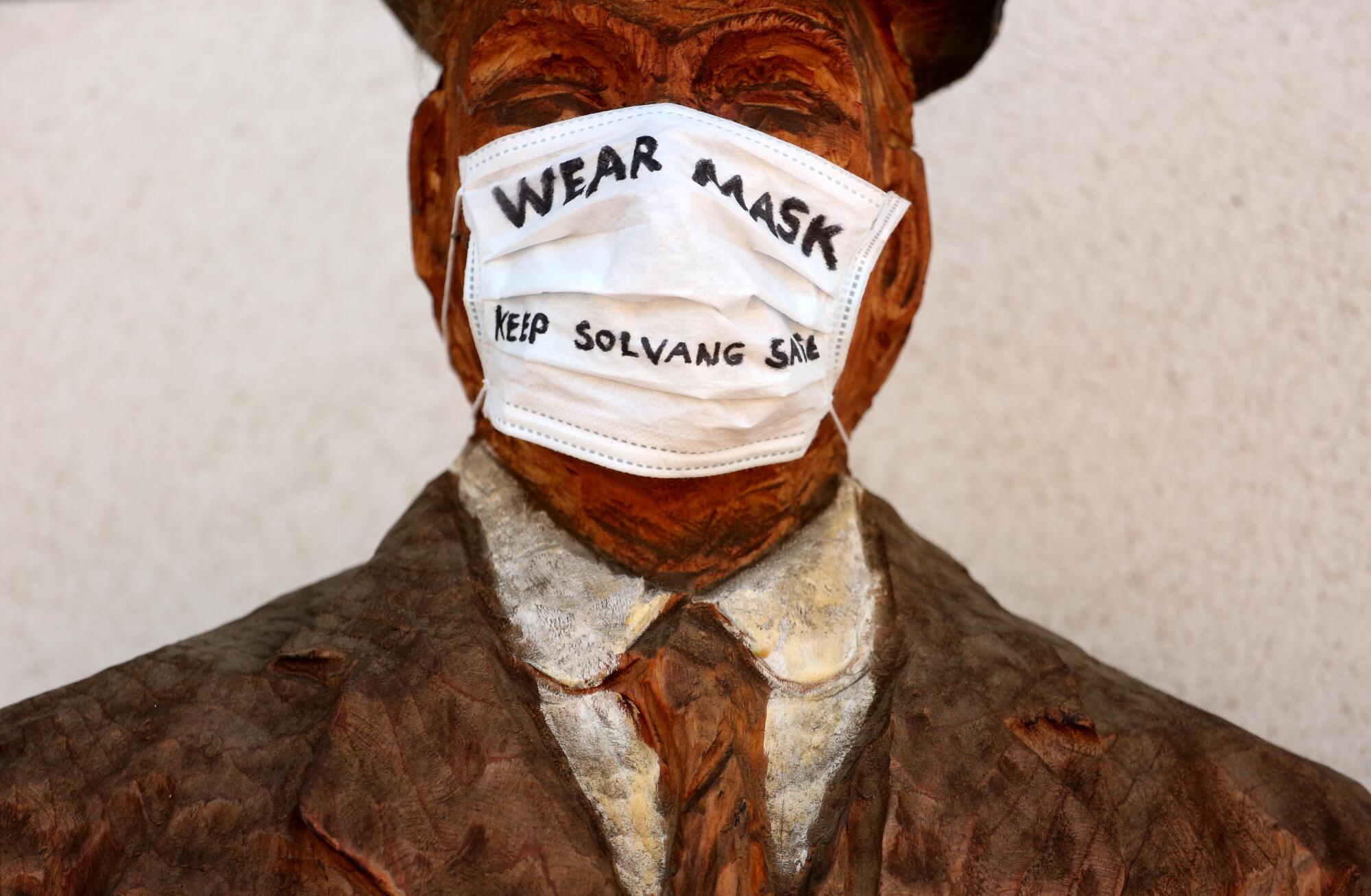

As Toussaint walked the lonely streets of the city center last week, a boy did skateboard tricks in the empty parking lot of a hotel whose red neon No Vacancy sign meant closed. In front of the Copenhagen House, a retail marketplace, the statues of Solvang’s Danish founders have been outfitted with protective masks.

Bent Olsen, who opened a thriving bakery in Solvang five decades ago and did so well he bought the hotel across the street and invested in a restaurant downtown, has furloughed more than half of his staff. He likens the current situation to the 1973 oil crisis, when gas rationing kept people from around Southern California, who account for 85% of Solvang’s visitors, off the roads.

But the hardship is relative, said Olsen, 76, who was born in Denmark in the waning days of World War II.

“After the war, that was not very good times,” said Olsen, whose bakery continues to sell pastries and coffee to go. “We kind of learned how to tighten our belt. You have to survive. That stuck with us for all those years.”

Not everyone is as stoic. About a quarter-mile down Mission Drive, the main road through town, Allan Jones has placed a sign in front of his real estate office asking passersby to honk if they want the shutdown to end.

So many obliged the noise forced Jones to take the sign down.

“A lot of people in this town are ready for things to open up again,” Jones said, peeking out from beneath a cowboy hat. “People are getting a little restless. We depend upon the visitors. People want to work and we’re being held back. It’s tough on them.”

“People are a little tired of this and frankly think it’s a bit overdone; you know destroying the economy and all that,” added Moore, the wine seller. “They’re willing to put up with it for a while but I think we’re getting pretty close to the end of it.”

The impatience is understandable given that the virus has made few inroads in the Santa Ynez Valley, with just five of the area’s 20,000 residents testing positive. The fact that Solvang and the surrounding tourist destinations have shut down has a lot to do with that because as the number of outsiders coming in drops, so does the risk of infection.

“There were a couple of residents that were really pounding on us back in January to stop the tour buses,” said Robert Clarke, Solvang’s mayor pro tem. “And this is before we really knew what was coming.”

Now there’s great uncertainty over how long many of the city’s merchants can hang on. The City Council have tapped $250,000 from Solvang’s general fund to pay micro loans to 50 businesses that have yet to receive help from the federal government. But that money is now depleted and the town’s coffers will continue to empty until the tourists return.

Nonprofit organizations, which fill the holes in the city’s safety net, are also going broke.

“As this drags on and people don’t have as much money in their bank accounts, they’re not donating to charity,” Clarke said.

Resources aren’t the only thing in short supply; time is running out too.

“Memorial Day is huge for Solvang,” said Birkholm of the holiday weekend that kicks off the busy summer period.

His family bakery, opened in 1951, is already preparing for that, ordering disposable menus and napkins and planning to spread out the tables for social-distancing purposes. The Solvang Brewing Co. is doing away with menus completely while removing its bar, dumping about half its tables and extending its patio into the parking lot in an effort to keep patrons apart once it reopens.

“The way that my business partners and me see it, it’ll be a new paradigm,” Bill Rodgers said. “People are going to be thinking quite differently so we are already exercising a lot of best practices in things like sanitation.”

And as they wait for the outsiders to return, the people of Solvang have turned to one another, which explains how a restaurant that opened two weeks after Newsom’s shutdown order has become one of the most popular in town.

Michael Cherney and his wife, Sarah, both L.A. natives who have lived in the valley for a decade, opened the peasants FEAST on April 1, having invested $180,000 in their dream — tens of thousands of dollars that went for chairs, tables, plates and silverware that have never been used.

“We were at the point where we were all in,” Michael Cherney said. “To stop and wait for a matter of months and then maybe get a bailout, we decided it wasn’t worth the risk.”

The locals rewarded the Cherneys’ pluck. The day they opened, serving takeout meals out of their parking lot, their old landlord bought $2,500 in gift cards and handed them out to his employees. Others have bought gift cards they’ve donated to needy families while the fire station down the street hands out paper menus and urges visitors to give the restaurant’s seasonal comfort food a try.

“We always knew that the locals are the bread and butter,” Michael Cherney said. “The community has always been real strong and supportive but maybe not as loud as they are now. Now they’re openly expressing, ‘We’re here to help you.’ ”

But there’s a limit to that help and the Cherneys say they probably can’t survive more than three months as a takeout restaurant. The hope is that once people are free to leave home, vacationers will make the short drive to Solvang rather than sit elbow-to-elbow next to a stranger on an airplane or pull on a dirty slot-machine handle in a crowded Las Vegas casino.

That was the city’s comeback plan after the 2008 recession and Clarke is certain it will work again.

“We’re better situated than some other towns,” he said. “The declines are always faster than the up-swings but yes, I’m pretty optimistic.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.