‘I am afraid for my life’: Immigrant detainees plead to be released

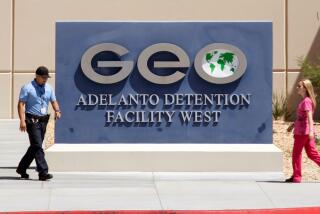

For weeks, as the coronavirus spread rapidly, Jose Hernandez Velasquez worried about the dangers of being detained inside the Adelanto ICE Processing Center 80 miles east of Los Angeles.

The 19-year-old Guatemalan immigrant listened uneasily as other men called their families, begging them to do everything possible to get them released so as to reduce their odds of contracting the deadly illness.

On Thursday, in light of the pandemic, a federal judge ordered immigration authorities to release Hernandez, an asylum seeker with hypertension who had spent nearly 2½ years at the facility in the high desert. When a guard came to tell him the news, Hernandez was speechless. Other detainees nearby burst into applause.

“I was really worried,” he said in a phone call after his release. “It was so difficult to be inside.”

As an increasing number of Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainees across the country test positive for COVID-19, California lawyers are working to free as many clients as they can by invoking constitutional rights and arguing on humanitarian grounds. In the last week, U.S. District Judge Terry Hatter Jr. ordered at least 10 people released from Adelanto, one of the country’s largest detention centers, holding nearly 2,000 people.

It’s unclear how many detainees have been released nationwide due to coronavirus concerns. In recent weeks, federal judges across the country have ordered the release of over 40 detainees.

Like Hernandez, most detainees have been released after lawyers petitioned federal courts on their behalf. Others have been released on bond or through humanitarian parole, which is free to people with a compelling emergency.

In response to the pandemic, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has instructed field offices to assess and consider for release those who were deemed to be at greater risk of exposure, reviewing cases of individuals 60 and older, as well as those who are pregnant. As of March 30, 600 detainees were identified as “vulnerable” and over 160 have been released from custody, according to the agency.

“Due to the unprecedented nature of COVID-19, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is reviewing cases of individuals in detention who may be vulnerable to the virus,” the agency said in a statement Tuesday.

In court filings, ICE has argued that concern about detainees contracting COVID-19 is “based on mere speculation” and that releasing large numbers of them would set a precedent that would persist even after the virus subsides.

In arguing for detainees’ release, immigrant rights advocates have pointed to jails and state prisons, which are trying to decrease the number of those inside to stem infection rates. California already has begun to process some 3,500 inmates to be released early in the next two months.

Until ICE agrees to release more detainees, “you’re going to keep seeing petitions like this,” said Jessica Bansal, senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, which got Hernandez and five others held at Adelanto released. “Because people need to get out.”

The ACLU has sued ICE facilities in multiple states over coronavirus concerns. A number of elected officials, including members of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, have called for stepped-up releases.

Late last month, the Southern Poverty Law Center and other groups filed an emergency request for the release of tens of thousands of people in ICE custody if the agency “cannot or will not take the steps immediately necessary to ensure high-risk individuals are protected from the virus.”

The preliminary injunction was filed in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles as part of an existing class-action lawsuit, Fraihat vs. ICE, which alleges that lax oversight has caused severe deficiencies in medical and mental healthcare in ICE facilities, as well as discrimination against detainees with disabilities.

As the number of confirmed coronavirus cases in California tops 16,000, advocates here have called on ICE to release detainees with underlying medical conditions who are at greater risk. Nationwide, ICE has confirmed 13 cases of COVID-19 among detainees, including one at Otay Mesa Detention Center in San Diego, as well as seven cases among facility staff.

On March 27, Hatter ordered the release of Pedro Bravo Castillo and Luis Vasquez Rueda, who were arrested by ICE after the state had gone on lockdown. Their attorneys believe that they were the first two detainees released from California facilities through court action.

“This is an unprecedented time in our nation’s history, filled with uncertainty, fear and anxiety,”Hatter wrote in his order. “But in the time of a crisis, our response to those at particularly high risk must be with compassion and not apathy. The government cannot act with a callous disregard for the safety of our fellow human beings.”

Hatter has cited that initial order in a slew of others made in the last week, including one ordering the release of An Thanh Nguyen, a Vietnamese refugee with asthma who was taken into custody by ICE during a check-in last month.

Nguyen was released from Adelanto on Friday, and his lawyer, Jenny Zhao of Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Asian Law Caucus, said the organization plans to file more petitions in the coming weeks.

“ICE needs to be going through who’s in detention and making these decisions on their own to release people,” Zhao said. “There has to be a larger-scale solution than lawyers filing a bunch of individual petitions, because that’s not going to be able to really deal with the scope of the problem.”

In response to Hatter’s orders for the release of Bravo and other detainees, ICE said the court should provide for their “immediate return to custody when the risk of contracting the coronavirus and the resulting risk identified” subsides.

In his decisions, Hatter has referenced a 2018 report on Adelanto from the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of the Inspector General that found “significant and various health and safety risks.”

At Adelanto, a holding area can contain 60 to 70 detainees, with a large common area and dormitory-style sleeping rooms that house four or six detainees, with shared sinks, toilets and showers. Lawsuits have noted that guards, detainees and cafeteria workers do not regularly wear gloves or masks and that detainees don’t have access to masks and seldom have access to hand sanitizer.

“The public has a critical interest in preventing the further spread of the coronavirus,” Hatter wrote. “An outbreak at Adelanto would, further, endanger all of us — Adelanto detainees, Adelanto employees, residents of San Bernardino County, residents of the State of California and our nation as a whole.”

ICE says it has taken steps to protect detainees from coronavirus infection, including medical screening of newly detained immigrants, monitoring staff, ending social visitation, increasing sanitation of common areas and offering detainees greater access to personal hygiene products.

In court filings, lawyers for ICE argued that conditions like those of Bravo, a 58-year-old with kidney stones, arthritis and a hernia, don’t rise to the level of vulnerability necessitating release.

“Many immigration detainees share these generic characteristics, and not just now but as applicable to other health crises,” the ICE lawyers wrote. “The disruptive effect of ordering petitioners released on this slim, hypothetical basis would long survive the COVID-19 pandemic, and the precedent would serve to release many aliens eligible for removal back into the general public.”

Immigrants detained for civil immigration offenses aren’t the only ones concerned about the pandemic. Those charged with criminal immigration offenses, such as entering the country illegally or reentering after a deportation, are held by the U.S. Marshals Service.

Lawyers with the Federal Defenders of San Diego said federal prosecutors have consistently denied requests for bond based on COVID-19 risks for clients who are awaiting trial for nonviolent offenses, calling their concerns “unsubstantiated and unwarranted” in court filings.

“Everybody wants to wash their hands of responsibility,” said trial attorney Marcus Bourassa. “We only have so many tools in our tool chest. The prosecutors hold the power in a lot of ways.”

For women with health issues, remaining in detention is particularly concerning. Agustina Pineda Ortuno, a 56-year-old from Mexico with asthma, hypertension and a damaged liver, among other conditions, said she has not been able to sleep since the pandemic began.

Pineda and three other women detained at Adelanto are named in a petition filed Saturday by Human Rights First and the law firm Morgan Lewis. In a federal court declaration, Pineda said her husband frequently sexually and physically abused her. She helped police to get him deported after he assaulted her so severely in 2005 that she sustained brain damage and was forced to have three surgeries.

With eight children to care for, Pineda said, she was arrested after working with family members to sell drugs out of her home. She served a year at a federal correctional institution and was transferred to ICE custody, where she has been for eight months.

Pineda said she sleeps in a dormitory with more than 20 women, some of whom have shown symptoms of coronavirus. She herself has a cough, and when the dormitory bathroom ran out of toilet paper last week, a guard told her to cough into a sanitary pad, she said.

“It is impossible for me to practice social distancing where I am,” she said. “There are a lot of people here, and I am afraid that I will get the virus.”

Pineda’s lawyer Katrina Bleckley of Esperanza Immigrant Rights Project has submitted requests for a new bond hearing and for humanitarian parole in light of the pandemic, applications that are filed to different agencies and require hundreds of pages of documents. Bleckley said she’s doing the same for her seven other detained clients.

“We’re doing anything that comes to mind for anybody,” she said. “I’m just doing all of it. Because they’re in a tinderbox — as soon as one person gets it, it’s going to spread like wildfire.”

Concerns about the novel coronavirus appear to be influencing release decisions even for immigrants who aren’t medically vulnerable. On Friday, an immigration judge at Adelanto granted a $7,500 bond for a Cameroonian asylum seeker in light of the pandemic. The man’s lawyer, Robyn Barnard of Human Rights First, said the same judge had denied his asylum case a month ago, which she is appealing.

Barnard said her client, who has been detained for seven months, fled Cameroon after being assaulted in a homophobic hate crime that led to his boyfriend’s death, after which police issued a warrant for her client’s arrest in accordance with the country’s anti-gay laws. Barnard submitted additional support for his bond last week related to the virus, including Judge Hatter’s March 27 decision ordering the release of Bravo.

“Given the court has been saying that conditions at Adelanto are generally not safe, hopefully we’ll see some cases coming soon for people who don’t necessarily have high-risk medical conditions,” she said. “Having anyone in these prisons that is eligible for release otherwise is really stupid at this point. ICE should be doing everything they can to alleviate the burden on our hospitals. San Bernardino County isn’t an area that has a ton of ICU beds.”

On Friday afternoon, an asylum seeker from El Salvador held at Otay Mesa Detention Center called a toll-free hotline run by the nonprofit Freedom for Immigrants.

He has cancer, he told Cynthia Galaz, director of the hotline, and he and 13 other people with health issues had been quarantined for more than a week. The man knew that two employees at the facility had tested positive for the virus and said he doesn’t believe that officials there are prepared for an outbreak.

“With this whole situation, though I have a lot of faith in God, I’m also human,” he said.

Later, a Guatemalan man with pneumonia called from Otay Mesa. He complained that the air conditioning blasting through the facility had worsened his cough.

“I am afraid for my life,” he said. “It would be terrible if we died inside here without seeing our families.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.