School closures stress families as coronavirus halts L.A. service centers

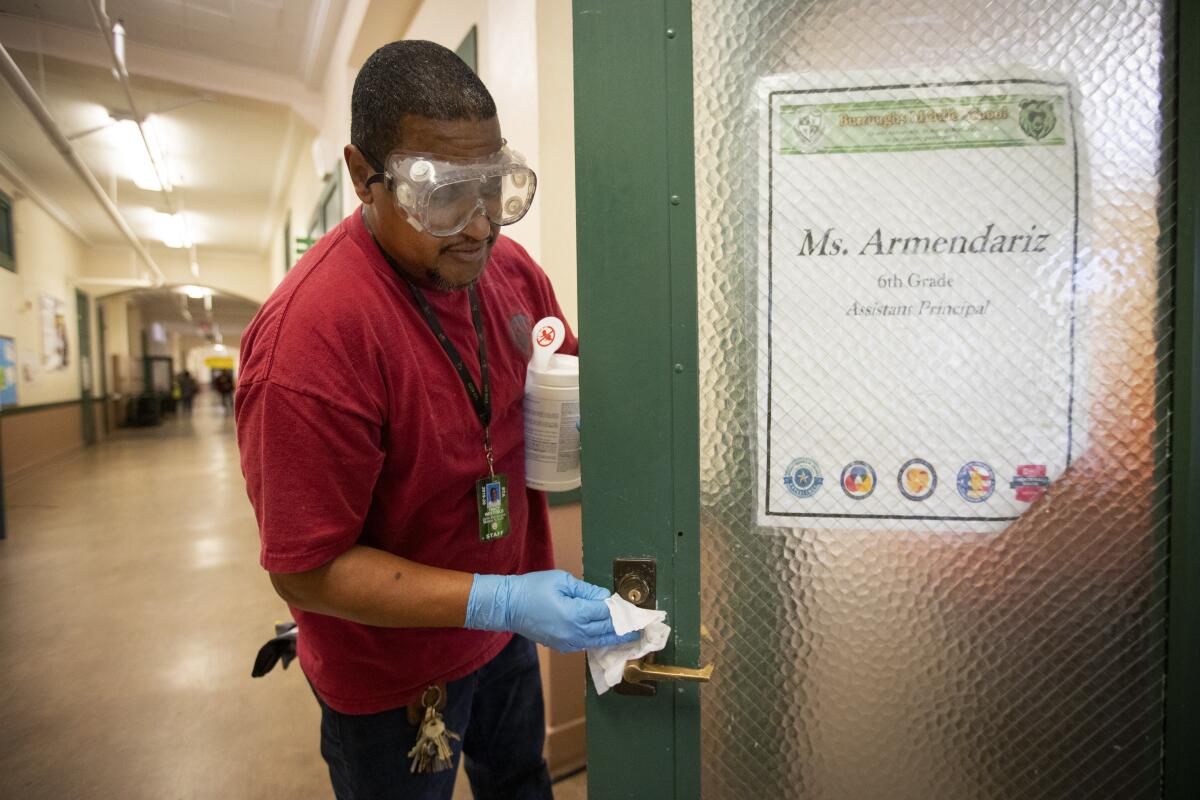

Millions of families in Los Angeles and across the state were forced to adjust Monday to closed schools, childcare hassles, an uneven move to online learning and a strained social safety net — the education system fallout from an unprecedented effort to halt the spread of the coronavirus.

L.A. Unified announced more bad news: District officials late on Monday canceled their innovative effort to offer childcare, counseling and learning materials at 40 new family resource centers, citing health risks.

Instead, 60 “grab-and-go” food centers will be available for school families. Locations are posted on the district’s website at https://achieve.lausd.net/resources and will be open starting on Wednesday, from 7 to 10 a.m.

“At this time, state and local health and public safety officials cannot assure us it will be safe for the children and adults at the family centers for us to provide care for children at these sites,” said Supt. Austin Beutner in a letter Monday afternoon. “We are deeply disappointed.”

With about 85% of California students out of school, many districts in the state were trying to move toward online education — an especially tall order in a state where 60% of students quality for free or reduced price meals because they are members of low-income households. In Los Angeles public schools the number is even higher, at 80%; in Compton it’s at 83%; Pomona, 89%.

Besides the potential for hungry children, in Los Angeles, for instance, this poverty also means that one-quarter of families do not have broadband service and additional families lack adequate data plans or computers needed to support online learning, Beutner said.

Those who have the least are likely to suffer the most in this emergency situation, according to child advocates.

“It’s critical for schools to continue prioritizing equity and directing resources towards high-need students in this crisis, as they face the greatest risks and uncertainty,” said Victor Leung, senior staff attorney for the ACLU Foundation of Southern California. “We must band together as a community and do everything we can to not let our most vulnerable students fall further behind.”

But this is all the more difficult because the act of coming together to help has become potentially dangerous — and the downfall of the service center plan. Beutner made the decision to open the centers last week, and in the rapidly moving coronavirus emergency, had to cancel their opening.

In an interview, Beutner said that L.A. schools “provide a social safety net for children ... The closing of any school has real consequences beyond the loss of instructional time.”

Monday morning, Julia Andres sat quietly on a green metal bench with her two school-aged sons as they waited for a city shuttle in MacArthur Park. The trio were heading to Andres’ job at a garment warehouse in downtown Los Angeles because she can’t afford daycare.

“I have to bring them to work,” she said. “I have to try and work whatever hours I can get.”

Tugging on his older brother’s hand, 10-year-old Miguel Petz, a fourth-grader at Vermont Elementary School, said he was worried about his parents being infected by the virus.

“I’m scared about it,” he said.

Miguel said he had a packet for homework that he would be working on, and that he would do other courses online using his older brother’s Chromebook.

Emmanuel Garcia, 13, a seventh-grader at Foshay Learning Center, said he was going to do most of his courses online, some through Schoology, an LAUSD online learning system. His feelings are mixed about schools being closed.

“We’re out of school,” he said. “But then we have homework.”

Beutner said the launch of educational programming during the school day on three public television channels in a partnership with PBS SoCal/KCET could provide support for learning for families without wifi. Each channel is specializing in a particular age range.

During the shutdown, teachers are expected to do what they can to keep learning going via online and electronic coursework and even paper homework packets.

Hildeliza Galicia and her family in South Los Angeles are struggling to sustain the basics and school work was low on the priority list Monday. Galicia works as a babysitter, helper and home organizer at four residences a week in Bel Air and Santa Monica and is worried about cancellations. Her husband Edgar, a truck driver at the port, has worked fewer hours in the last few weeks due to reduced imports from China.

Their children — son Daniel, 9, and daughter Alondra, 16 — are both home from school. Daniel attends a charter school and Alondra goes to an all-girls private school.

“I have to arrange whose going to babysit who,” Hildeliza Galicia said.

Los Angeles students and parents faced both technical problems and logistical issues on their first day. In a Facebook group for LAUSD parents, some said they didn’t have enough laptops and computers to share between multiple children. Parents also expressed concern about the emotional well-being of their children, and how they would react to not seeing friends and having routines disrupted.

Evelyn Macias, a writer and publicist in Reseda, said her biggest concern was keeping a positive atmosphere at home and reassuring her high school daughter and older daughter attending Reed College in Portland.

“The big question for me is how do I continue to make them feel that this is something that too shall pass?” Macias said. “How do I continue to make them feel comfortable, safe?”

Her younger daughter Lucy Macias — a 10th-grader at the Cleveland Humanities Magnet High School — said she is worried about missing in-person lectures. “There’s a lot of hands-on instruction and I don’t know if we can really get that through the internet,” she said.

Other districts are grappling with similar problems, including the Las Virgenes Unified School District, which serves the western San Fernando Valley and the eastern Conejo Valley.

“We’re very concerned about the impact of isolation on our children’s well-being,” said Supt. Dan Stepenosky. “We’re also working on a way for high school students to connect with elementary students to build connections virtually and we have opened our district-wide counseling center to our students, their families, and our staff. All appointments are via Zoom.”

“Out of crisis comes opportunity,” he said hopefully.

Pomona Unified mobilized to offer meal service, providing cold breakfast and lunch trays in a “drive-through” set up at five locations between 7:30 and 9 a.m.

“Breakfast and lunch meals are handed to families through car windows for the number of children present in the car,” the district advisory states. “Meals are not to be eaten on premises ... Meals must be eaten or refrigerated within two hours from pick-up time.”

The 900-campus Los Angeles Unified, which serves about 670,000 children and adults, is initially expected to be shut down for two weeks. However the closures may last last longer.

As of Sunday, 24 of the state’s 25 largest school systems had closed their campuses. The remaining district, the Kern High School District in Kern County, with about 40,000 students, said plans for “impending closure” are underway.

Even for families with some flexibility, the options are limited with libraries, museums, recreation centers and other gathering places closed.

Carmen Adler, a history teacher at Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies, a grade six to 12 school, is worried that the daycare center her two children attend will close, affecting her ability to help her students. Her husband is also a teacher.

“It’s not like one of us can take the kids to the park while the other takes shifts,” she said. “A lot of places are closed ... We’re literally stuck in the house.”

Times staff writers Sonali Kohli and Sonja Sharp also contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.