In Joshua Tree, the county is cracking down on vacation rentals, sparking a backlash

JOSHUA TREE, Calif. — This high-desert gateway to Joshua Tree National Park is in an uproar over what some see as heavy-handed enforcement of a new law aimed at reining in hundreds of Airbnb units and other short-term rentals created during a construction boom.

The controversy erupted in January when San Bernardino County enforcement officers armed with clipboards, cameras and laser measuring devices started prying into the bedrooms, bathrooms and kitchens of once sleepy neighborhoods, where some homeowners had ignored building and safety codes for decades.

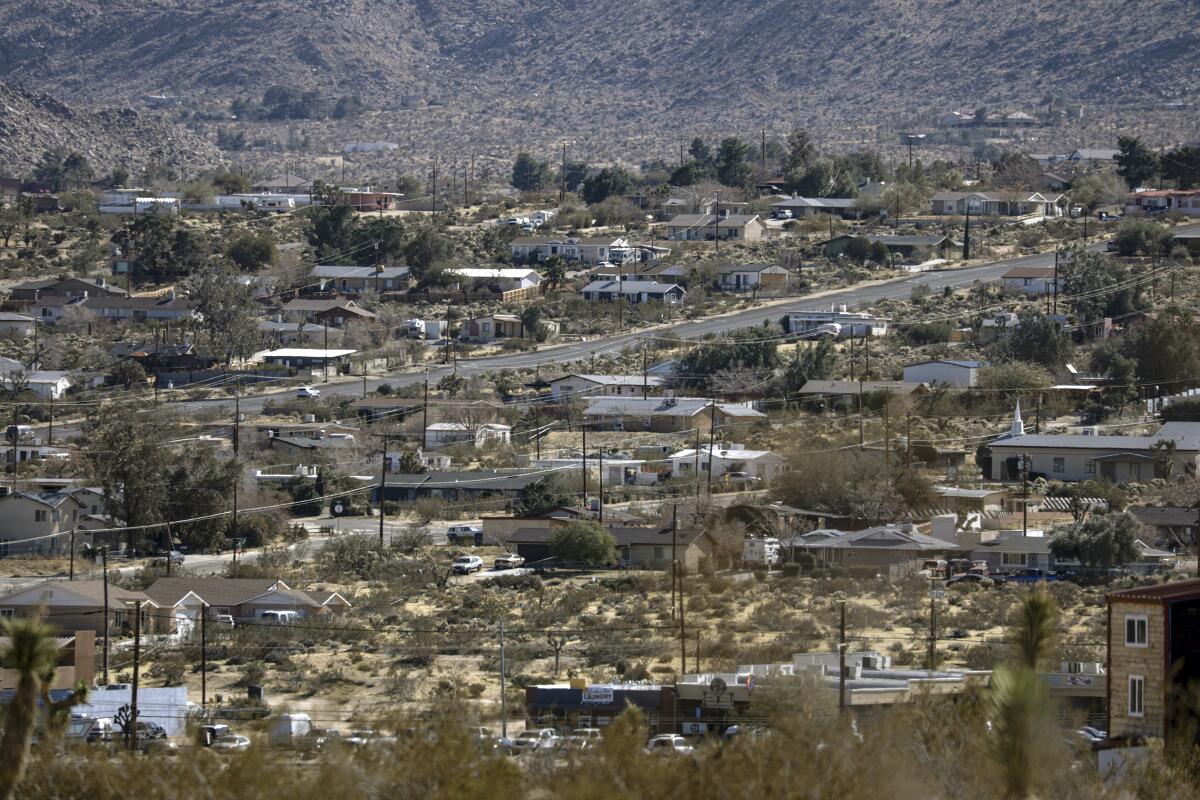

The inspections are required under the new law, which took effect in December, in order to obtain a permit to continue operating a short-term rental in this town of about 9,000 residents. Far from wealthy but blessed with an abundance of nature, this community of sun-scorched modest homes and low-slung motels is nestled in an otherworldly landscape of weather-sculpted boulders and spindly Joshua trees, near a national park that receives 3 million visitors a year.

Many property owners figured they had little to worry about. Now, “there’s a perception that inspectors are overreaching,” Peter Spurr, a real estate agent in Joshua Tree, said on Tuesday as enforcement officers were making the rounds in compact vehicles emblazoned with the county logo.

Spurr said he gets about 80% of his business from buying and selling short-term rentals, and he’s getting calls from owners wondering if they should cash out.

“The concern is that they could trigger a wave of panic-driven property sales that could drive down home values and crater our local economy,” he said.

County officials say the area’s number of unregulated short-term rentals has skyrocketed by 21% over the last year to an estimated 1,160, contributing to a shortage of affordable housing stock and traditional long-term rentals. The unincorporated town, which sits along California 62 about 30 miles north of Palm Springs, has a median household income of about $37,700, compared with about $60,100 countywide, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“The county is aware of complaints about home inspections,” said David Wert, a county spokesman. “We’ve reminded our code enforcement inspectors that these property owners are our customers and to treat everyone with dignity.”

“But we didn’t tell them to stop writing violations — just to be courteous,” he added.

Although county inspectors say they have no choice but to enforce the new law, four years in the making, homeowners who created short-term rentals out of their residences are facing up to building and safety violations they cannot easily afford to correct.

The law applies only to short-term rentals. The county has yet to come up with a plan to gain control of hundreds of “alternative rentals” — tepees, freight containers, crude lean-tos, Sherpa huts, travel trailers and yurts.

Residents are fighting back by filing complaints to county agencies and scrutinizing the findings of enforcement officers.

Clint Stoker, a building contractor and planning commissioner in the nearby city of Yucca Valley, said he has spent more than $25,000 on improvements at his rental properties in Joshua Tree, including a 75-year-old Spanish-style home with a pool that rents for $600 a night.

“A lot of people are scared and upset,” Stoker said. Enforcement officers, he added, “are dinging people for every possible unpermitted improvement they can find: recessed lights, water heaters, partitions, hot tub valves, kitchen cabinets, sinks and floor space and the number of available parking spaces — you name it.”

Stoker said that some of the county’s listed violations are in error. “So, homeowners have started comparing notes. If we can prove that enforcement officers were wrong, we can force the county to relax its enforcement policies.”

County officials have given homeowners until March 31 to apply for a permit to continue operating. So far, the response to the crackdown has been less than cooperative. As of Tuesday, only about 90 homeowners had filed an application.

Thomas Fjallstam, who heads the Joshua Tree Gateway Communities Vacation Rentals Assn., a group of roughly 450 property owners in the area, has postponed filing a permit application with the hope that what he described as “overly invasive county inspectors” will become more lenient amid rising protests.

“I’m going to wait and see what happens out there,” he said. “I don’t want them to search my house and then have to respond to a flurry of code enforcement notices.”

Fjallstam claims that county officials misled the community into thinking that code enforcement officers would primarily be looking for possible health and safety violations, such as smoke detectors and fire extinguishers.

“Instead, they’re going over every inch of an applicant’s home with a microscope,” he said.

Joshua Tree has always been a close-knit oasis for nature lovers, rock climbers and hikers, with musicians and artists drawn to the town after the 1973 overdose death of Flying Burrito Brothers singer Gram Parsons in Room 8 of the Joshua Tree Inn.

In recent years, several residents and outside investors have pushed to transform Joshua Tree from a primarily low-cost weekend resort to a place where families, professionals and big spenders might spend a week or more. That has triggered pushback from those who fear that more rentals will mean more traffic, all-night parties and trespassing.

But many rental owners, merchants and restaurateurs depend upon the sometimes-disruptive summer pilgrimage of college students and hangers-on for their livelihoods.

A narrow dirt road leads to a bluff overlooking town, where there is a unique escape marked by a hand-painted sign that says, “Please respect our privacy.” Amanda B’Hymer, who moved to Joshua Tree in 2001 and raised a daughter there, presides over the 65-acre spread. For years it has been a destination and creative workplace for creative types that locals like to call Joshua Tree’s “desert tribe.”

B’Hymer‘s boyfriend, Patrick Hutchinson, 59, is a live recording engineer for the Eagles of Death Metal, a Joshua Tree band that was on stage at a music venue in Paris on Dec. 7, 2015, when gunmen stormed in and opened fire, killing 90 people.

She markets to visitors who want to chill in one of her tiny rustic cabins decked out in 19th century motifs, with windows that offer panoramic views straight out of a Hollywood western set.

Standing in the bedroom of a little cabin favored by repeat customers, B’Hymer said, “We just spent a lot of money on improvements here including a new roof. Now, the challenge is to try and survive an inspection, which doesn’t seem fair.

“The county doesn’t understand us,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.