Kobe Bryant’s helicopter was missing a warning system that could have alerted pilot to hillside

The helicopter that crashed Sunday in Calabasas, killing nine people including Kobe Bryant, was not equipped with a terrain alarm system that could have warned the pilot he was approaching a hillside, National Transportation Safety Board officials said Tuesday.

The findings came as investigators were trying to determine why the helicopter crashed into a hillside amid foggy conditions.

NTSB investigator Jennifer Homendy said at Tuesday’s news conference that the helicopter was at 2,300 feet when it lost communication with air traffic controllers. The helicopter was descending at more than 2,000 feet per minute at the time of impact.

“So we know that this was a high-energy impact crash, and the helicopter was in a descending left bank,” Homendy said.

The chopper hit the hillside at an elevation of 1,085 feet, about 20 to 30 feet below an outcropping of the hill. But even if the pilot had been able to fly above the hilltop, he would have faced new hazards ahead.

“There are actually other higher hills surrounding it,” said Bill English, a lead investigator.

A reconstruction of the flight by The Times tracks the helicopter’s path starting at a crucial moment near the end when the pilot left the San Fernando Valley above the 101 Freeway.

Homendy said her agency had recommended that the Federal Aviation Administration 16 years ago require that all choppers carrying six or more passengers be equipped with a terrain awareness and warning system, adding that the FAA has “failed to act” on the proposal. Because the FAA didn’t follow the recommendation, the chopper that crashed Sunday was not legally required to have the system.

Shortly after her Tuesday news conference, an FAA spokesman disputed that assessment, noting that the FAA requires the terrain alarm systems for helicopter air ambulance operations.

It remained unclear what the pilot knew about the terrain surrounding him or if he had become disoriented.

Bryant regularly used the helicopter, owned by the charter service Island Express.

Kurt Deetz, a former pilot for Island Express who said he flew Bryant from 2014 to 2016, previously told The Times that he thought the aircraft was outfitted with a terrain warning system, but when reached Tuesday, he acknowledged that he might have been mistaken.

“The NTSB knows way more than I do,” Deetz said.

Deetz said it was unlikely such a system could have averted the crash, had the helicopter been equipped with it.

NTSB Board Member Jennifer Homendy briefs media on the Jan. 26 helicopter crash in Calabasas, Calif.

Authorities investigating Sunday’s accident said the impact of the crash was intense, shattering the chopper and sending debris over a wide area.

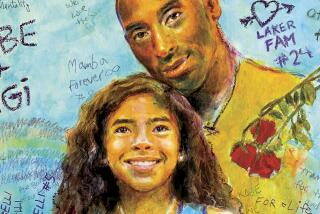

The new revelations came as the bodies of Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, and seven others were recovered.

The investigation into the cause of the crash is still in its early stages, but officials have revealed some details about the final moments of the flight, which was taking Bryant and his group from Orange County to his basketball camp in Thousand Oaks. The retired NBA player was scheduled to coach a game in which Gianna was scheduled to play.

Accompanying the Bryants were John Altobelli, 56, longtime baseball coach at Orange Coast College; his wife, Keri, 46; their daughter Alyssa, 13; Christina Mauser, 38, an assistant basketball coach at the Mamba Sports Academy; Sarah Chester, 45; Chester’s daughter Payton, 13; and the pilot, 50-year-old Ara Zobayan.

Just before crashing into the hillside, the pilot rapidly ascended to avoid a cloud layer, according to the NTSB.

The helicopter — a Sikorsky S-76 chopper built in 1991 — departed John Wayne Airport in Orange County at 9:06 a.m. Sunday, according to publicly available flight records. The aircraft passed over Boyle Heights, near Dodger Stadium, and circled over Glendale during the flight. The NTSB database shows no prior incidents or accidents for the midsize helicopter.

Homendy said Zobayan requested special visual flight rules (VFR), which allow pilots to fly visually in controlled airspace when ceilings are less than 1,000 feet or when visibility is less than 3 miles, during the trip to Ventura County because weather conditions had deteriorated.

At some point during the flight, the pilot requested “flight following,” a process in which controllers are in regular contact with an aircraft and can help them navigate, according to recordings of radio communications between the air tower and the aircraft.

Nine people, including Kobe Bryant, were killed when a helicopter crashed and burst into flames in Calabasas.

Before the conversation ends, the tower is heard telling the pilot the helicopter is too low for flight following. Radar data indicate Zobayan, who had been a licensed commercial helicopter pilot for 19 years, guided the copter to 2,300 feet and then began a left turn. The helicopter then began rapidly descending.

A visual-flight-rules flight “is based on the principle of see and avoid.” When operation of an aircraft under visual flight rules isn’t safe, often because of inclement weather, a pilot can opt to fly under instrument rules (IFR). During this type of flight, the pilot navigates only by reference to the instruments in the cockpit, according to the Federal Aviation Administration.

Pilots “fly VFR when and if weather conditions allow, although they can choose to fly on an IFR flight plan at any time,” said Ian Gregor, an FAA spokesman. “Also, it’s always up to the pilot to make the decision whether to fly VFR and to ensure the safety of the flight and adherence to federal aviation regulations.”

As authorities worked to recover victims’ remains early in the week, a stream of visitors, Bryant fans and tourists came to the area, wanting to see the site for themselves. Some had cameras. A few had binoculars. Basketballs, candles, balloons, photos and various tributes lined a fence near the entrance to Juan Bautista de Anza Park in Calabasas.

The NBA star’s death struck Westlake Village resident Chad Martinson as doubly cruel. The 35-year-old father of two brought his 5-year-old daughter, Tatum, to the memorial, which he acknowledged was emotional.

“His death as a father hits me harder than him as a player,” Martinson said. “The second I heard it was Kobe in the helicopter, I knew where he was going, and the first thing that popped into my head was, I was hoping the girls wouldn’t be in the helicopter.

“It was devastating to hear that his daughter was with him.”

As Tatum struggled to pull her father away from the tributes and closer to the playground, Martinson lifted his daughter and gave her a hug.

“I grew up watching Kobe and saw him in Venice Beach [in 1996] the day he broke his wrist in a pickup game,” Martinson said of Bryant, who had been traded to the Lakers as a teen. “I’ll always have that memory of his toughness, and now I’ll have to pass that to my daughter.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.