Meet the woman who brings thousands together to count L.A.’s homeless population

The hand-drawn thermometer on the wall had just jumped to 7,100, assuring everyone in the command center that this year’s homeless count would have enough volunteers. But for Clementina Verjan, in charge of every count since the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority began conducting them in 2005, that didn’t mean all was well.

She knew it would be next to impossible to spread that many people across Los Angeles County in an even manner. Some locations would have too many volunteers and some would have too few.

“We never have a shortage of volunteers for skid row,” she said Tuesday.

So, on the first day of the federally mandated point-in-time count of the homeless population, Verjan was in her office downtown, scanning a computer readout of 163 deployment centers in churches, parks and community centers. It didn’t take long to find a location that needed help.

PHOTOS: 2020 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count

Only 12 volunteers had signed up to cover Avocado Heights in the center of the San Gabriel Valley. Seventy were needed. So about 6:30, Verjan slipped on her LAHSA jacket and headed to her car to do what she has done for years — count homeless people.

Verjan, 47, joined the homeless services agency in 1999 to prepare a grant application to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. When HUD required homelessness agencies to start documenting the number of people they were serving, she was given the additional role of helping organize what became L.A.’s first point-in-time count.

It was 15 years ago when 250 paid workers and 750 volunteers scoured a sample of the county’s census tracts. Verjan had retained a consulting firm to design a counting method suitable for the sprawl of Los Angeles.

The method developed then, sending people to visually survey sampled census tracts, remains the foundation for LAHSA’s now-annual count.

What’s changed over the years is the volunteer force — so large now that it is able to cover every street in the county except for the cities of Pasadena, Glendale and Long Beach, which conduct their own counts. Each year, more cities, quasi-governmental homeless coalitions, councils of government and church groups join the effort.

For some, the motivation is self-interest: city leaders who complain that the count was too high or too low, and want to make it better.

Verjan now oversees a staff of 14. They prepare, in part, by assembling clipboards and maps for more than 2,100 census tracts.

Many have criticized the methodology, which is at best an approximation because it involves a statistical adjustment of inherently subjective observations from lightly trained volunteers. But it has become a major civic event, bringing people across the county together in a single purpose.

Volunteers, including those who have been homeless, recruit others to join them up to the last minute. A website allows volunteers to register and pick out the neighborhood they’d like to cover.

Verjan believes the experience of people working side by side with neighbors and community leaders has enhanced awareness of the problem of homelessness.

“If they can share that experience about what it means to do the count, they can have that discussion with individuals who have a different train of thought about what homelessness looks like,” she said.

On Tuesday, Verjan arrived at San Angelo Park in Avocado Heights shortly before coordinator Gabriela Gomez began handing out clipboards to a dozen volunteers. Each clipboard covered a census tract. With 29 tracts, the volunteers split into teams of two, instead of the recommended three to four, and each had more ground to cover.

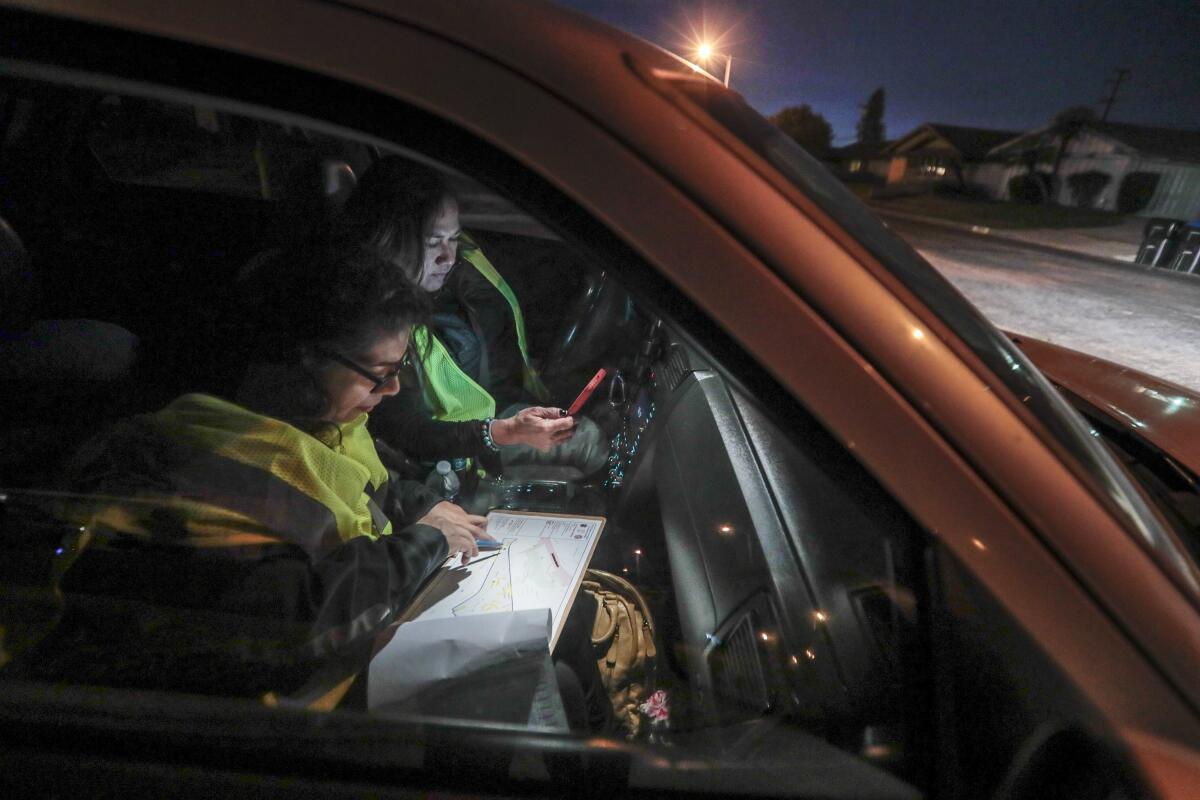

Verjan teamed up with Lisa Flores, an administrative assistant with Dunn-Edwards who chose to drive, leaving Verjan as the navigator and counter.

On the maps of their five census tracts, streets seemed logical. But at night, in an unknown neighborhood, driving in and out of dark cul-de-sacs, under freeways and back and forth on commercial streets, the logic faltered.

Several times, Flores stopped the car to read a destination into her phone and learned she needed to make a U-turn.

In the unincorporated area just east of the San Gabriel River, neighborhoods quickly transitioned from middle class to working class. Few people were out on the darkened back streets. But there were many RVs and a few beat-up automobiles.

The challenge was deciding which ones were owned by the people who lived in the nearby houses and which ones were being lived in.

Verjan, a veteran at point-in-time counts, made quick decisions on most.

“Nope, nope, nope,” she said as Flores moved slowly down each street. They stopped to discuss several RVs. Were they old and damaged? Were the windows covered on the inside? Were they parked where they would attract little attention?

Each got a thumbs-up or thumbs-down.

Verjan and Flores, the last team in, returned to San Angelo Park about 11:30 p.m. Their numbers weren’t high: half a dozen RVs, three individuals and a few shopping carts. But they had covered every street in their five census tracts.

On Wednesday, the pattern would repeat, somewhere on the Westside.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.