Boys, girls and genders in-between: A classroom lesson for modern third-graders

School counselor Holly Baxter had prepared for this moment for months. She gathered the third-graders of Red Oak Elementary on the carpet for story time, opened the picture book and began to read.

Casey, she said, likes to play with blocks and his dump truck, but he also loves things that glitter and shine.

Casey admires his sister’s glittery nail polish and says that he wants to wear it too. His sister tells him boys don’t wear glittery nail polish.

“Right, Daddy?” she asks their father.

“Most boys don’t wear nail polish,” their dad replies. “But Casey can if he wants to. There is no harm in that.”

Story time in this Oak Park Unified classroom last month unfolded in a way that relatively few 8-year-olds in the country have ever experienced.

The story by Lesléa Newman, the concepts, the questions and the answers between students and teacher culminated in a pioneering — and at times volatile — chapter in this suburban Ventura County school district after educators decided to teach elementary school students about the complexities of gender.

Baxter continued reading from the book.

When Casey and his sister were going to the library, Casey wore a shimmery skirt.

“Mama!” his sister cried. “Why is Casey dressed like that?”

“Because that’s how Casey wants to dress,” Mama said. “I don’t think Casey looks silly. I think Casey looks like Casey.”

Children, meet “Sparkle Boy.”

The explosion

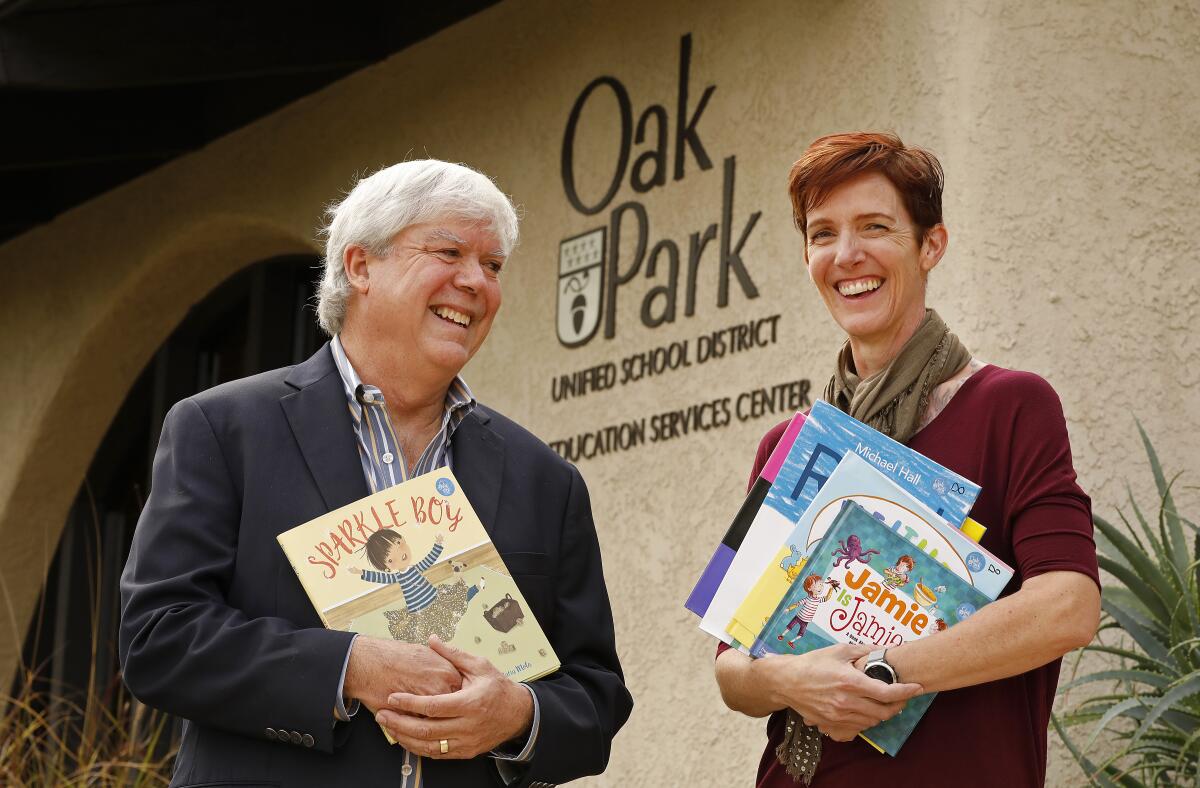

The email blast from school Supt. Tony Knight hit parents’ inboxes on July 30.

Oak Park, a well-off, well-educated and politically diverse community, prizes its high-performing public schools. In 2019, Oak Park High School ranked among the top 100 high schools in California, according to U.S. News and World Report. The district has won several awards for its robust environmental education program.

Now administrators planned to introduce bold, new school lessons about gender identity.

“It is expected that some families will be uncomfortable with this discussion, especially when it comes to how it is shared with children,” Knight wrote in the letter. “It is important, however, that our own personal uncertainties do not interfere with our ability to do the right thing to protect the safety and well-being of vulnerable children.”

The email touched off what Oak Park Board of Education President Denise Helfstein described as the most explosive controversy during her five years on the board.

More than 300 parents converged in September at a back-to-school meeting designed to address the issue. Outside, a small group of parents passed out fliers that called the lessons “unscientific ideology.”

“The school has made a choice to do this and be progressive and I respect that,” Amy Sitarz, who has three children in the district, said in an interview. “But I think they’ve crossed the line, as far as teaching my child what I believe should be taught at home.”

Inside, the parents’ questions turned into a crash course for adults on gender diversity.

It’s tantamount to sex education, some parents said.

Baxter explained that gender identity is separate and distinct from sexual identity.

“We’re not talking about who you’re attracted to and we’re not talking about biology,” she told parents. “We’re talking about gender as it’s an authentic sense of self, and how a person feels about themselves in the world.”

Lessons will be developmentally appropriate, last 45 minutes and will occur once a year, she added.

Parents said that while they support anti-bullying initiatives, talk of gender complexities should stay out of the classroom.

“It’s confusing enough being a child,” said Lester Kozma, an Oak Park parent. “Parents are the only ones who know whether they’re ready for these kinds of talks.”

John Mallon, who has a second-grader in the district, said, “We’re now throwing this into the schools and saying, ‘This is normal. This is OK.’”

Actually, educators replied, it’s a good move.

They cited a 2015 National School Climate Survey, which showed that three-quarters of gender-nonconforming students felt unsafe at school. They explained that hostile school environments are among the factors that contribute to disproportionately higher rates of depression and suicide among LGBTQ youth.

Medical and research communities increasingly recognize that some people do not identify exclusively as male or female. The American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy statement in 2018 that recognizes gender diversity and the ever-evolving array of labels that come with it, as well as the importance of affirming those identities among children.

Yet only a handful of school districts in the country — including San Francisco, Oakland and Seattle — have introduced these concepts at the elementary level.

Some parents asked for an “opt out” option so their child could be excused from the lesson.

“If we had an opt-out program for this,” Knight said, “it would make it sound like it’s potentially something immoral or obscene. And it isn’t.”

And according to the California Education Code, parents can opt their children out of sex and HIV-prevention education only, not discussions about gender.

Helfstein, the school board president, agrees that the subject is sensitive. She’s participated in numerous one-on-one meetings between administrators and parents, who’ve been encouraged to freely ask questions about the lessons.

The district had originally planned to define to fourth- and fifth-graders the terms transgender, non-binary (those whose gender identities fall outside the categories of male or female) and cisgender (those who identify with their gender assigned at birth). But after collecting feedback, they decided to explain the concept that gender sits on a spectrum.

Helfstein said it’s been hard to gauge which proportion of parents disapproves. Critics have cited concerns about their religion, ethnicity and family values.

“I didn’t know very much about [gender diversity], and I’ve learned a lot from this process,” Helfstein said. “I know how it feels to not want to say the wrong thing.”

A pressing need

In the fall of 2018, it became clear to Baxter that transgender and gender-nonconforming students were struggling. Up to 10 students, or their parents, sought her out for counseling every school year.

Some of the students suffered from severe anxiety and depression. Parents of the youngest — one in first grade and another in third — said their children were shunned in more subtle ways, such as not being invited to birthday parties.

Parents told Baxter that their kids were crying at night, afraid to go to school and wanted to change classrooms. And the parents, too, harbored fears for their isolated children.

The rejection wasn’t felt only by transgender and non-binary students.

One girl in fifth grade asked to speak to a counselor after being teased for mostly hanging out with boys; she didn’t really connect with the other girls. But now the girls were calling her a boy and taunting her for the way she dressed.

‘It’s confusing enough being a child.’

— Oak Park parent Lester Kozma

While administrators focused on how to support these students, Baxter saw a pressing need to create a safe and compassionate campus culture.

“If they’re not seeing themselves represented in what we teach, they get a sense that who they are is not a part of the culture, that they are some kind of a secret, that they are something to be ashamed of,” Baxter said.

Supt. Knight agreed.

Knight, who has served as a public school teacher and administrator for 40 years, recalled gender-nonconforming students he knew in the district in the 1990s, when he was a principal — and before language existed to describe them and what they were experiencing.

“I didn’t really know how to address the issue, to help the parents, to help the child, to help the teachers. And it was just something that everybody just chose to ignore,” Knight said. “I think that we all came to a revelation here in the school district, because of the way we love and care for our kids — that this is not something that can be ignored any longer.”

The California State Board of Education approved a new health education framework in May that offered guidance about how to talk to elementary school students about gender identity.

“While students may not fully understand the concepts of gender expression and identity, some children in kindergarten and even younger have identified as transgender or understand they have a gender identity that is different from their sex assigned at birth,” the kindergarten-through-third-grade guidelines state. “The goal is not to cause confusion about the gender of the child but to develop an awareness that other expressions exist.”

Knight and other administrators felt it was essential to begin teaching these lessons in the lower grades. A student as young as 5 had already transitioned, and a few wanted to be called by pronouns such as “they” and “them,” the most common identifiers used by non-binary people. Other students were talking about it among themselves, and they had a lot of questions.

Non-binary is also now a legally recognized gender category in California, meaning that residents can identify themselves as such on their driver’s licenses and birth certificates.

Baxter, Knight and other educators wanted to normalize gender diversity concepts from the get-go, so that these ideas inform the way they think about themselves, their peers and human nature.

Without controversy, the lessons were unanimously approved by Oak Park’s Board of Education on April 23 after a review by the curriculum council and parent-teacher organizations at each of the three elementary schools.

Sense of relief

When Oak Park parent Avon Dinh heard about the gender diversity lesson, she was elated for her second-grade son, Sawyer. As soon as Sawyer could talk, Dinh said, he was telling his parents that he wasn’t a girl.

Sawyer began identifying as a boy by kindergarten. When he shared the fact that he’s transgender with classmates, they have been mostly kind, but are sometimes confused, his mother said.

Sawyer uses the boys’ restrooms, and boys have asked him why he uses the stalls instead of the urinals. A few times his peers have peeked over the stall.

Dinh tells her son that it’s not his job to educate his classmates.

“I hate putting that pressure on him,” Dinh said. “Adults should be giving them the words for this.”

Mara Smialek, mother to an Oak Park second-grader, said she is glad that the district is “teaching children that everybody is different and our differences are what make us special,” something she already makes a point to teach her kids at home.

While some parents are having a hard time with changes, she said, she knows there is a lesson in that too.

“I hope the kids learn that even if you don’t understand or aren’t comfortable with something in the beginning, it’s important to be respectful and accept people for who they are,” Smialek said, “instead of trying to judge or change somebody.”

Back in Room C-33

Baxter held up her copy of “Sparkle Boy” and asked the third-graders to consider why the words “sparkle” and “boy” usually don’t go together. She then explained that the book title defied stereotypes.

The kids made a few guesses at what that word, “stereotype,” means. With Baxter’s help, they came up with a definition: When you think you know something about someone just because of the group they belong to. Or when you assume the trait of one person applies to everyone in their group.

Baxter then drew three boxes — labeled “boy,” “girl” or “both” — on the smartboard, and told the students to sort words into these categories. First up was “sports,” which she placed in the “boy” box to get the game rolling.

“That’s not right!” one girl exclaimed.

‘I hope the kids learn that even if you don’t understand or aren’t comfortable with something in the beginning, it’s important to be respectful and accept people for who they are.’

— Oak Park parent Mara Smialek

“Why?” Baxter asked.

“Because I like sports, and I’m not a boy,” the girl said. Everyone agreed that “sports” belonged in the “both” box.

With each new word, the students grew more excited. Dancing is for both! Art is for both! Pink is for both!

At one point, a boy piped up and said, “Casey wants to wear sparkly things because Casey is really a girl.”

LGBTQ migrants face extortion, death threats and assault after they’re sent south of the border

“Remember what we talked about stereotypes?” Baxter replied. “You can still be a boy and wear sparkly things. Clothes don’t tell you what your gender is.”

Baxter had sent the lesson plan to parents the day before and would send them an update on how it went. Four or five students on average have been absent for each lesson, though only a few parents have called in to say they kept their children home to shield them from the curriculum.

She explained to the children that gender is how they think of themselves as boys or girls. But some people don’t think of themselves as either, or somewhere in the middle.

Just like a rainbow has a variation of colors, with many different shades of orange and purple, there are many kinds of boys and girls, Baxter said. Some people, she added, don’t fit on the rainbow at all.

“So tomboys are in the middle?” one girl asked.

They talked about the term “tomboy,” and how some people don’t like being called that, while others don’t mind it.

“But we always respect how people like to be referred to, whether that’s a girl, a boy, tomboy, girly girl or a sporty boy,” Baxter said. “All of those things are OK.”

Resources

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.