Column One: Guilt drove him to keep his brain-injured wife alive. What would she have wanted?

SAN DIEGO — It was Valentine’s Day 2010 when Steve Simmons asked his wife, Rafaela, to go on a motorcycle ride. She wanted to stay home, he said. He was the one who loved motorcycles. Not her.

“It’s not as fun when you’re a passenger as [when] you are the driver,” Steve said. Rafaela went along to make him happy.

Steve and Rafaela went riding with friends that Sunday from San Diego to Oceanside. They were on an easy, slow stretch of Pacific Coast Highway that runs mostly along sandy beaches, taco shops and high-end fish houses that cater to tourists. They were near Carlsbad, less than five miles from the halfway point, approaching an intersection that should have gone by as an unremarkable blur, when a young woman drove her car through a stop sign.

Steve saw it coming, but there wasn’t enough time to lay down his bike the way he was taught when you’re about to broadside a car. The front tire of his motorcycle caught on the car’s rear bumper and catapulted Rafaela, who was wearing a helmet, to the ground.

Steve blacked out. He’d broken his wrist and separated his shoulder. What happened next was hazy, as he drifted in and out of consciousness, except for a sound he distinctly recalled.

“I heard her gasp,” he said. Paramedics had to cut a hole in Rafaela’s windpipe so she could breathe.

Rafaela, 51 at the time, had suffered a severe brain injury. She slept and woke, her eyes opened and closed. Her reflexes continued to function. Sometimes she yawned, or smiled, or cried.

But she was in a persistent vegetative state.

After she had been in the ICU for 27 days, doctors asked Steve: Did he want to disconnect his wife from the life-sustaining treatment — feeding and breathing tubes — and transfer her to hospice care? Or did he want to send her to a nursing home to continue treatment, even though she had almost no chance of recovering?

For Steve, who was 53 then, that decision was complicated by more than grief. He blamed himself for Rafaela’s condition.

In California alone, at least 4,000 people statewide are kept alive with breathing and feeding tubes. That number includes only those covered by Medi-Cal, the state’s insurance plan for the poor and disabled.

They are the Terri Schiavos no one has ever heard of. Schiavo was the Florida woman whose life and death were the subject of legal and political battles in the 1990s. Schiavo’s heart stopped when she was 26. She was resuscitated and kept alive with a feeding tube. Her husband wanted the tube removed, arguing she wouldn’t want to live that way. Her parents believed otherwise, and the struggle dragged on until 2005, when the tube was removed. Schiavo died 13 days later.

An L.A. Times Studios podcast about the search for a man’s identity.

In California, state law allows Steve to make this decision on behalf of his wife.

He decided on treatment, because he believed she wanted to live.

I first met Steve in 2014, while working on an investigative series about people kept on life support. Over the next five years, I spent hours interviewing him in person or on the phone. Often, I sent him questions by email.

“I wanted to write about the first time you saw her on the beach in Mexico,” I once emailed him. Remembering who Rafaela was before the accident was painful to Steve. He almost always responded late in the evening.

“It was the month of July, midafternoon when I saw my wife for the first time. I remember that it was extremely hot and humid and I couldn’t fathom how someone could lay on the beach in that sun,” Steve replied.

“Did she like the sun? The water?”

“She loves the sun but is not comfortable in the water. She can’t swim.”

I look back at those emails, one excruciating question after another.

“Do you remember the last thing Rafaela said to you before the accident?”

He couldn’t recall.

‘Wait ... I’ll go with you’

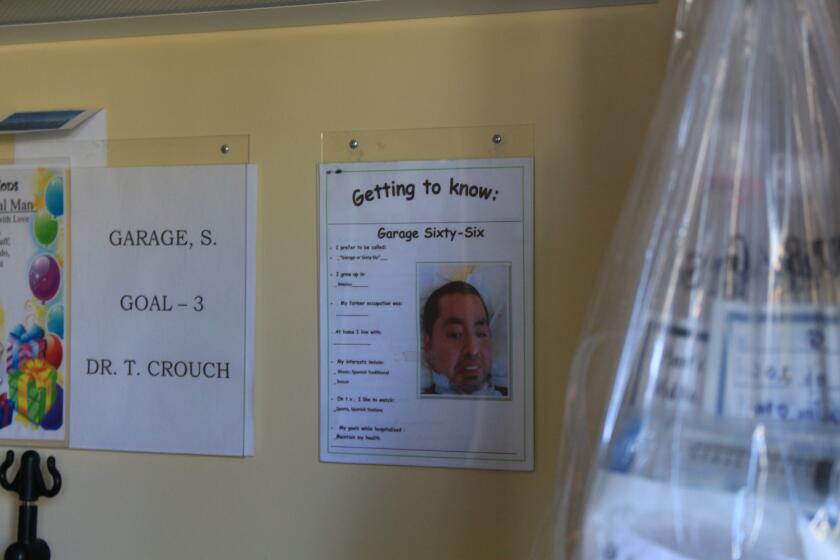

Rafaela was transferred to the Villa Coronado Skilled Nursing Facility in Coronado in San Diego County. It’s housed in two buildings across the street from each other. Steve considered Rafaela lucky. She had a room in the newer building. When he toured the place, he saw the older one first.

“I walked out,” he said.

It was the smell. He couldn’t take the smell.

Steve was determined to do everything possible to keep his wife alive. He researched everything he could about brain injuries and spent hours each day by Rafaela’s bedside.

For the first time, he turned to God.

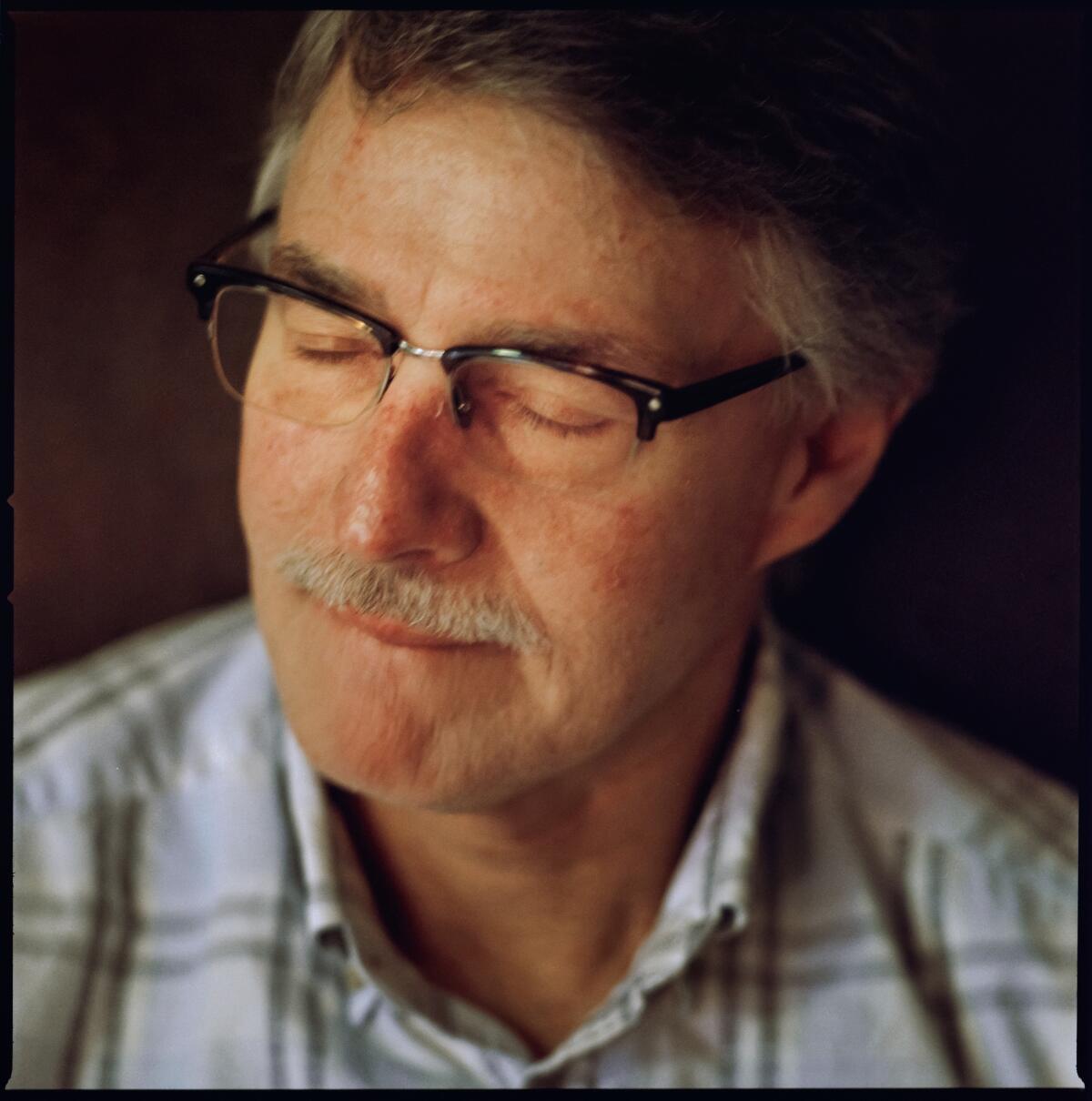

When he had to go back to work five months after the accident, he hired a full-time caregiver to be with her when he couldn’t. He settled into a routine, visiting Rafaela every day after work, Saturday afternoons and all day Sundays. A few times a year he’d take a weekend for himself and camp alone in the desert. There were times, he said, when he just wanted to die.

Like the night he stopped his car on the Coronado Bridge, a two-mile snake of a road high above San Diego Bay. Its 34-inch railings are an easy hurdle for someone like Steve. Someone looking for a way out. It had been only months since the accident.

“It’s almost too tempting,” he said.

It was late and there wasn’t much traffic. Steve slowed his car to nearly a stop and looked in his rear mirror.

And then something happened, he said.

“God spoke to me. That’s why I didn’t get out of the car.”

God told him he was being selfish and that he needed to live so he could continue taking care of Rafaela.

Steve called his mother that night.

“I want to jump off a bridge,” he said to Cathy Simmons.

“Wait until I get there,” Cathy said. “I’ll go with you.”

Cathy felt that she’d already lost her daughter-in-law, Rafaela, and she couldn’t bear to lose Steve too. If he was going to jump, so would she.

Cathy kept Steve on the phone that night and persuaded him to get medical treatment, antidepressants and therapy. But nothing, she said, would alleviate Steve’s guilt.

But still he persisted

Rafaela’s skin was too smooth for a woman in her 50s. Perhaps it was a byproduct of the accident. She had lost her ability to speak, to smile willfully, to frown, to gesture in a meaningful way, arresting the lines that come from everyday life. Her hair was short and finely streaked with gray, a sign Rafaela was indeed aging and growing old in her hospital bed.

Rafaela did not have an advance directive — a document stating her wishes should she become medically incapacitated. Only about one-third of Americans do.

Steve was certain that Rafaela was aware, that she just had no way to tell anyone. During his visits, he spoke to her, told her he loved her, played her favorite CDs, rubbed lotion on her arms and placed the bracelets she once made on her wrists.

“Absolutely she had awareness,” Steve said. “She got to the point where she would turn her head and look for people.”

Rafaela’s doctor, Ken Warm, said Rafaela was likely blind, although he had no way of knowing for sure.

“There’s probably some very sophisticated ways of determining if a mute person who can’t move is blind, but it was not available to us,” he said.

Rafaela would sometimes blink when Warm spoke to her, but he didn’t know whether it was random or purposeful. She did seem to follow Steve’s commands, Warm said. She could squeeze a ball in her right hand when Steve asked her to.

Despite Rafaela’s devastating brain injury, she was generally healthy. She didn’t get the bedsores and infections that people on this unit are prone to have.

Steve’s schedule focused around work and visiting Rafaela. “[I’d] go home and do the same thing every day,” he said.

His mother worried about him.

“How can you keep on?” Cathy asked him. “How much longer?”

Steve told her that this was his life.

In a way, Cathy understood. Her husband had Alzheimer’s and she’d been his caregiver for the last 12 years of his life. “That’s what you do,” she said. “You just make sure you don’t leave them.”

In Rafaela’s seventh year at the Villa, Steve, normally congenial and hopeful, was beginning to sound defeated. It was as if something had punctured the protective bubble he’d worn all these years. His resilience was finally giving way to reality. But still he persisted.

He’d found a place in Texas that was supposed to be good at rehabilitating brain-injured patients, but it was private and he couldn’t afford it. Home seemed like the best option. Steve was 59 by then and had learned about a Medi-Cal program that would help retrofit his condo to accommodate his wife. So he had come up with a plan: In two years, when he could retire, he was going to bring Rafaela home.

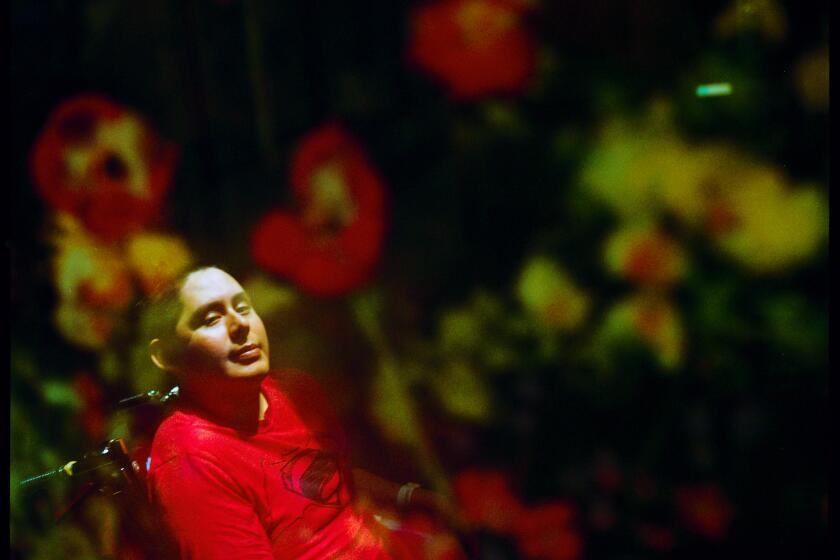

Finding out his name turned out to be the easy part. The tough part was navigating the blurred lines that separate consciousness from unconsciousness — and figuring out whether his smile was really a smile.

Months later, Steve said he had something to tell me. He was his usual buoyant self again.

“I’ve made a decision,” he said.

I knew what he meant. I’d reported on end-of-life issues long enough to know the code. Making a decision meant he was finally ready to let Rafaela go. After a few minutes of awkward conversation, I got the sense Steve was looking for affirmation from me.

I thought of his mother, Cathy, who had once said that she prayed for Rafaela to either wake up or die.

“I think your mother would be happy to have you back,” I told him.

About a week later, in July 2017, I sent Steve an email. I asked him whether he’d spoken with the nursing home’s advanced care planner, the person who helps counsel families in these situations.

Ten days later, Steve responded. He’d changed his mind.

“Given my wife’s ability to communicate via her left hand as well as being able to nod yes or no I can’t imagine doing anything other than seeing what the future has in store for her.

“Every day I ask her if she would like to wear one of her bracelets and she nods and raises her hand so I can put it on her.”

It’s time

In year eight, Steve noticed that Rafaela slept more often. He began to ask her about heaven.

“‘Do you want to go be with Jesus?’ And she couldn’t give me a response.”

Steve’s greatest hope had been for his wife to recover. He’d been around the nursing home long enough, seen plenty of people languish for years in this excruciating limbo, that now he hoped for something else, that Rafaela could tell him whether she wanted to live or to die.

His answer, in part, came from a colleague at work. The two had found a common bond — her husband had been sick and had also been on life support. When he could no longer speak for himself, she was the one who decided to withdraw treatment and let him go.

The work colleague began visiting Rafaela at the Villa, sometimes with Steve and sometimes on her own.

One day, she said to Steve, “Your wife wants to go. She’s begging you.”

Steve was beginning to believe that it might be time.

“All of a sudden, I thought, what if something happens to me?” Steve said.

He worried Rafaela would become like the woman in the bed next to her. Alone, with no one to visit.

“I thought about my wife and how she was before, and how she enjoyed life,” he said. “She’s not dancing, she’s not laughing, not eating her Mexican food, not able to do anything.”

Since the accident, Steve had read a lot about brain injuries and consciousness, and more recently, about death and dying. In year nine, he read a book about preparing for the end of life, “and how beautiful it should be, given the right circumstances,” he said.

He wanted Rafaela to finally find peace. She deserved her “dignity back,” he said.

In October 2018, almost nine years after the accident, Steve decided to withdraw treatment. “There was no one specific thing” that triggered his decision, he said, but a combination of things. Mostly, it was time.

“It took that long to forgive myself,” Steve said.

Omar Salgado defied the odds in Room 20. But his is not a story about a miracle — it’s a story about medicine’s inability to accurately diagnose consciousness.

Forgiveness

LakeView Home is a 1950s house on a residential street lined with palm trees in east San Diego County. It looks like any other house on the block, but for the discreet sign near the front door, “Bringing comfort to each day.” No one would guess this is where people come to die.

On Nov. 14, 2018, Rafaela was transferred here, to a bedroom with a twin bed covered in a white and yellow quilt and a window facing the front street. A leather recliner was tucked into a corner of the room, so Steve could be comfortable.

Rafaela could have received hospice care at the Villa, but Warm, her doctor for the last nine years, didn’t believe the people who had worked so hard to keep her alive for so long should have to cope with helping her die.

At LakeView, the 20-hour mechanical feeding stopped. Margaret Elizondo, Rafaela’s hospice doctor, said that without the forced feedings she needed less suctioning — the procedure in which excess secretions were vacuumed from her chest through the hole in her throat.

When Rafaela was suctioned at the Villa, she’d sometimes jolt upward in bed and wince, as though she were in pain.

“What we were doing to try to prolong her life, thinking that we were doing good, we were also doing harm,” Elizondo said.

The breathing and feeding tubes, the suctioning, the medications — they had kept Rafaela alive. Depending on your point of view, they either prolonged her life or prolonged her death.

Rafaela “died on that day that she was on that motorcycle nearly a decade ago, and we tried to pretend that that wasn’t what happened,” Elizondo said. “We don’t know when to let go.”

Without the feeding, Rafaela became more somnolent and her eyes were closed more often. Without hydration, her kidneys began shutting down. She was given medication for pain and to keep her breathing comfortably.

Now, instead of asking Rafaela to squeeze his hand, Steve told her that he was going to be OK and that he loved her.

On Saturday night, 10 days after Rafaela was admitted to hospice, Steve lay down beside his wife in her bed.

“I cried very hard and asked for her forgiveness.” He decided in that moment to forgive himself.

When Steve returned to LakeView the next morning, he knew it would be Rafaela’s last day.

“She would take these large gasps of breath that were difficult to watch,” he said. “And she would do that for 10 minutes and stop.”

They were alone together when Rafaela took her final breath. “The color in her face was still so beautiful,” Steve said.

He stayed with her for 20 minutes and stroked her hair. “I know you’re above,” he told her.

Then he walked into the hallway and looked for a nurse.

“I think my wife has passed.”

He didn’t cry until he got in his car to drive home.

One year after

About a week after Rafaela’s death, Steve went back to the Villa to visit with the people who had cared for her for so long. He stood outside her room, but couldn’t bear to go in.

Since then, he’s spent time traveling; he’s road-tripped through the desert and hiked one of the most deserted trails of the Grand Canyon. And he’s spending time with his 1-year-old miniature schnauzer, Camila.

He retired in May, and plans to leave San Diego and move to Utah to be closer to his mother and the rest of his family. That’s where he’ll be Monday, the one-year anniversary of Rafaela’s death.

Steve has no plans to formally mark the occasion. Instead, he’ll reflect, he said, about what’s past and what’s still to come.

By letting Rafaela go, Steve decided to live.

“Which is what she would have wanted.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.