California suffered widespread cellphone outages during fires. A big earthquake would be much worse

When Ted Atz, a 75-year-old retiree in Marin County, learned that his power would go out during the Kincade fire, he texted his loved ones that he might lose cell service.

He was right. For four long days, Atz couldn’t make or receive calls. He’d drive around his hometown of San Anselmo, hoping to find better reception. He had no luck and was frustrated by the knowledge that if he suffered some kind of medical or other emergency, he couldn’t reach 911.

“I would have liked to let family know that I was OK,” Atz said.

Atz wasn’t alone. California saw significant interruptions of cellphone service due to the planned power shut-offs at precisely the time customers needed to be alerted about evacuation warnings — raising questions about how prepared California is for future electric shut-offs and other public safety emergencies, such as a major earthquake.

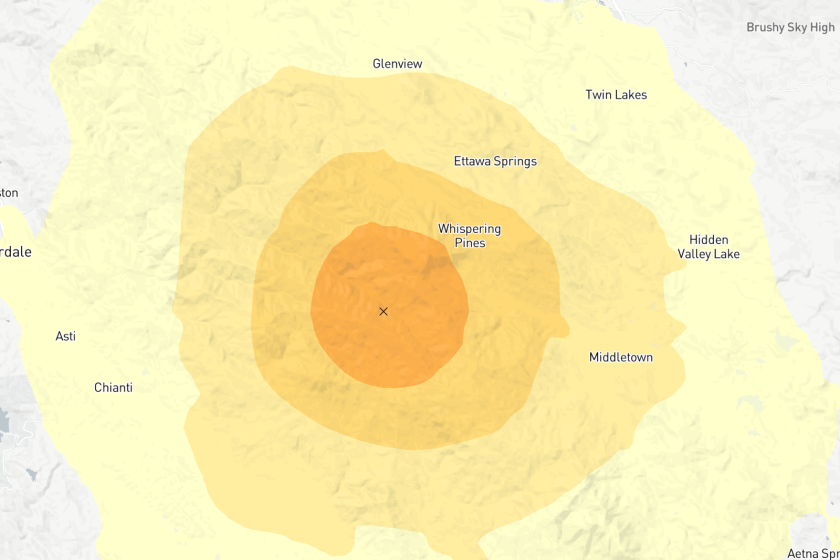

At one point, Marin County saw 57% of its 280 cellphone tower sites out of service. Other counties also saw major disruptions: Sonoma, Lake, Santa Cruz, Humboldt and Calaveras all encountered days in which more than 20% of cellphone towers were out; Napa County saw a day when 19% of cell towers were not working, according to data released by the Federal Communications Commission.

In the central Bay Area, San Mateo and Contra Costa counties saw more than 11% of cell towers fail to work.

The problems weren’t limited to cellphones. Some customers who get their landline phone service through their broadband internet service provider saw their phone lines go out, despite having their phones charged and equipped with battery backups.

Even traditional copper-based landline phones had problems in at least some areas. A resident of Lake County said his AT&T copper-based landline phone signal cut out following the first 24 hours after the lights went out; he said he was told by AT&T that there’s limited backup power for that system. He lost phone service for a combined five days over the course of three power outages.

Local government officials and consumer safety advocates were incensed at the widespread phone service failures, which came despite days of warnings that the power would be shut off to help prevent ignition of wildfires by power lines and other electrical equipment damaged from severe Diablo winds.

Sonoma County Supervisor Lynda Hopkins, whose district includes areas under evacuation during the Kincade fire, said that the cellphone network outages posed significant safety concerns.

Fire stations were forced to communicate by radio, creating excess traffic at a time when officials had to rapidly deliver information about an active fire.

And while evacuation warnings were delivered before the planned power shut-offs, Hopkins said residents in rural communities without cellphone or internet service would have had no way to receive additional warnings.

“Had there been a second fire, had the fire suddenly been reinvigorated and moved quickly toward some of these communities, we would not have been able to effectively communicate with the residents,” she said.

Federal regulators said they do not release data on how many cell signal sites went down by company.

Phone carriers said they did the best they could.

Heidi Flato, a spokeswoman for Verizon, said in an email that the company has generators and backup batteries at most of its cell towers and at all of its switch locations.

“While we are doing everything we can to minimize the impact of the [power shut-off], there are discrete areas of our network that will experience service disruption or degradation, due to topographical and other technological constraints,” she said.

AT&T spokesman Ryan Oliver said that before the Kincade fire, the company deployed hundreds of additional generators and technicians from across the country, and had crews working 24 hours a day to refuel and deploy generators as needed.

A statement provided by T-Mobile spokesman Joel Rushing said the company deployed and refueled generators to more than 260 sites. Permanent generators are in place at key cell sites, while others are prepared with a battery backup; the company also has a fleet of temporary generators that can be deployed as needed.

Comcast’s Xfinity services require commercial power to operate, spokeswoman Joan Hammel said in a statement.

“Generators may be deployed in a limited manner to address Comcast outages in vital public safety facilities,” the statement said. There may be situations when a home’s power is on, but the part of the network that provides a connection to the home has no power, and as a result, communication services are unavailable.

Consumer advocates, however, say the carriers failed to keep phone signals alive at precisely the moment they were needed most — when customers needed to communicate with loved ones and receive evacuation warnings.

There are no federal or state regulations that mandate cell carriers have any backup power for cell service, said Ana Maria Johnson, program manager with the Public Advocates Office, an independent organization of the California Public Utilities Commission that advocates on behalf of consumers.

“What this tells us is that the communications network is vulnerable. It’s not resilient. The companies were not prepared. And requirements must be put in place to require backup power,” Johnson said.

“Consumers rely on their wireless networks to call 911, and they expect those networks to work.”

Johnson’s office has urged state regulators to require backup power for cell towers, saying the FCC and state officials have talked about doing so but have never acted on it. “The commission should require wireless facilities to provide backup battery power and generators for their wireless communications facilities located” in high fire threat zones and floodplains, the office said in a filing.

In an interview, Johnson said cell carriers should be required to have a minimum of 72 hours backup electricity supply at the site of the cell tower.

After this incident, phone companies should be required to disclose which cell sites went out and when it happened, and include details such as the type of backup power, whether generators were brought in, what worked and what failed, said Regina Costa, telecommunications policy director for the consumer advocate group the Utility Reform Network.

“The point is to fix this problem and have reliable service, because this is life and death,” Costa said.

State Sen. Mike McGuire (D-Healdsburg) has already introduced legislation, SB 431, that would mandate backup power systems lasting at least 48 hours for wireless towers in the state’s highest fire risk areas.

“In an era where many households no longer have landlines, telecommunication companies provide a critical public safety service during a disaster,” said Hopkins, the Sonoma County supervisor. “We cannot have those systems go down when we most need them…. In my opinion, it’s only a matter of time until we see loss of life.”

Cell service can be crucial to the ongoing function of a society during and after a crisis. Widespread outages of cellphone networks following hurricanes or major storms have been a consistent problem in the United States, interfering with recovery efforts. In Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, residents roamed roads searching for signals; cellphone towers in the New York City area were disrupted after Superstorm Sandy.

In Japan, it is required that cellphones have a 48-hour backup power supply, said seismologist Lucy Jones, author of “The Big Ones: How Natural Disasters Have Shaped Us (and What We Can Do About Them).”

There was some discussion as to whether such a standard should be required in Los Angeles to prepare for earthquakes, but it became clear several years ago that neighborhood groups would oppose having diesel-powered generators at wireless tower sites across the city, which would need to be tested monthly, said Jones, a former science advisor to Mayor Eric Garcetti.

A prolonged power outage — and lack of cell service — can cause major problems for recovery. The hardest-hit areas in Japan after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami ran through the 48 hours of backup supply, but electricity wasn’t going to come back soon. “When they lost cellphones is when people gave up and left the area,” Jones said.

People who couldn’t track down loved ones during the Kincade fire had to result to an old-school approach: the radio. Listeners called into KBBF-FM (89.1), a multilingual radio station in Santa Rosa that broadcast news in Spanish and indigenous languages, hoping for word from families that had gone quiet during the outages.

Rafael Vazquez, a KBBF host, suggested listeners check in with the county and update their status as safe in case their relatives were looking for them.

“People would say, ‘I cannot get a hold of a sister, I don’t know where my mom or my dad went, we were supposed to connect but now I’m not able to connect with them,’” he said.

Sofia Olmedo, 32, had been keeping her sister-in-law updated on her whereabouts as she fled the city of Windsor with her two children, husband and other relatives. When they found refuge at a ranch in Napa County, owned by her husband’s employer, Olmedo’s phone lost service. She stopped receiving government emergency alerts.

“I felt sad and frustrated that I couldn’t call to tell her that I was OK,” she said.

Her husband was eventually able to get in touch with her sister-in-law using his phone, which operated under another carrier, and Olmedo used a solar-powered radio to listen to news from KBBF about the fire.

When she returned to Windsor, she went to her carrier’s store to pay her phone bill.

“It’s not fair that I’m paying for this service and I didn’t receive it,” she told the representative.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.