Does a rain-free October signal a return to drought in California?

“There are 200 different definitions of drought,” said climatologist Bill Patzert. “If you’re a firefighter with no rain in the month of October, and there are strong Diablo and Santa Ana winds, it’s a drought.”

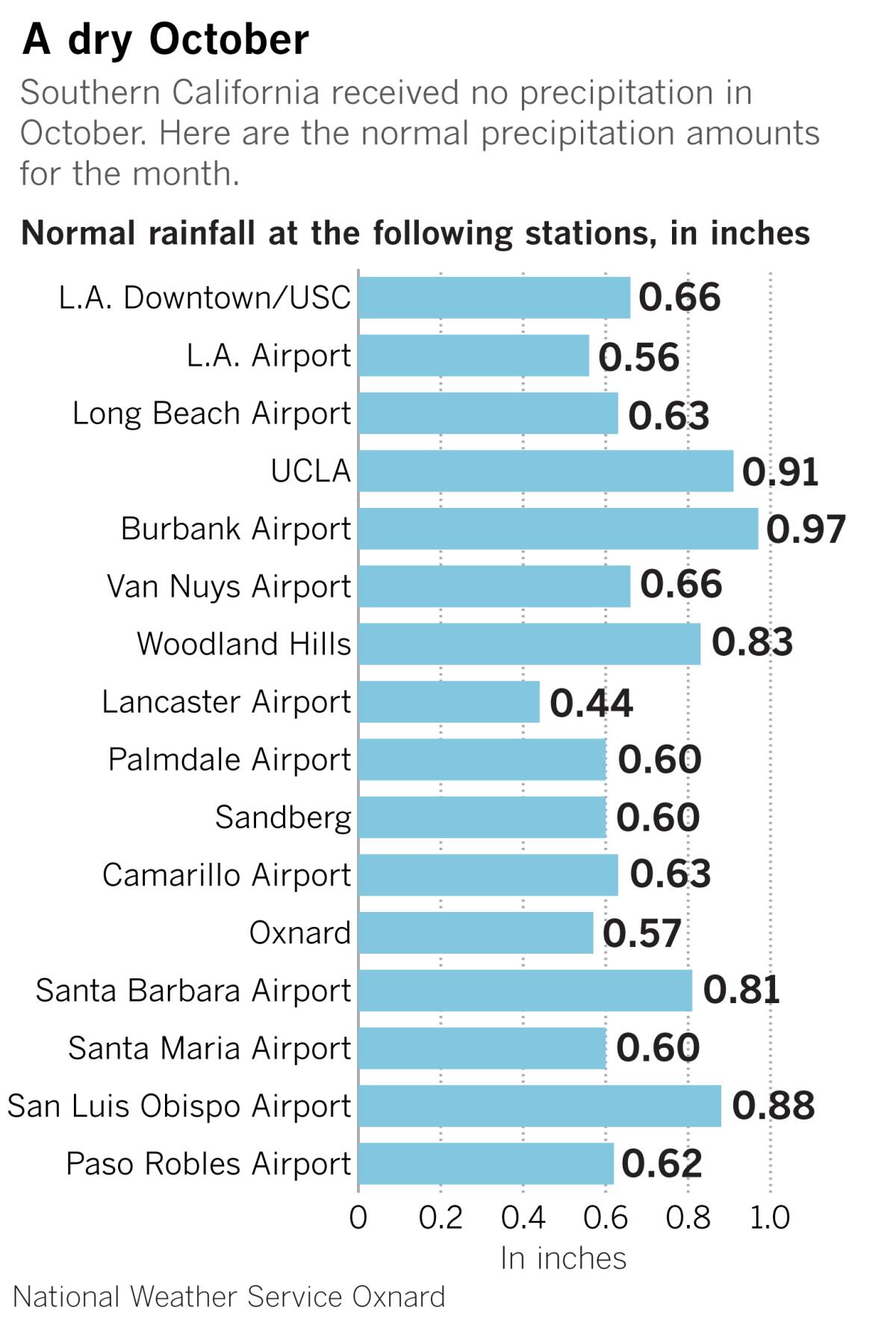

Southern California got no rain during October, and it was desiccated by super-dry Santa Ana winds.

The jet stream that fed cold air into the Great Basin last week, fueling strong Diablo and Santa Ana winds in California, could have been delivering the first rain storms of the season from the Gulf of Alaska if it had been positioned about 500 miles to the west.

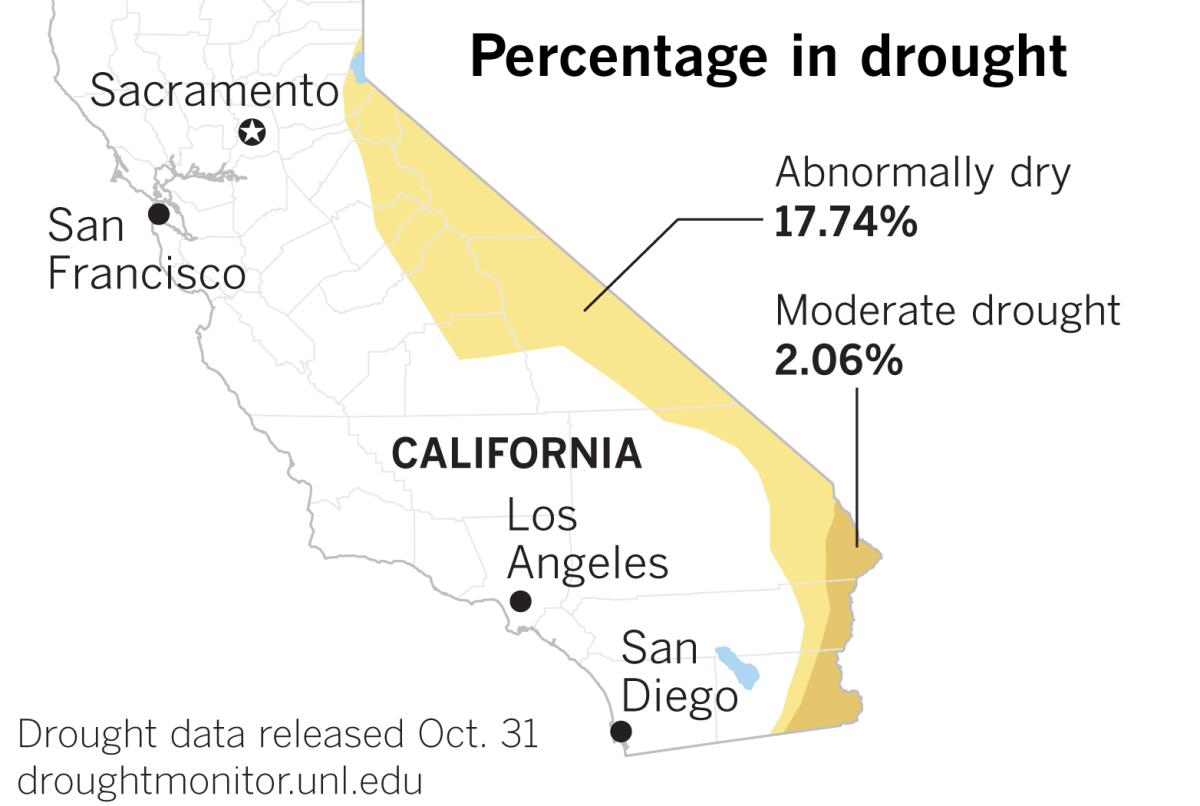

According to the Drought Monitor, almost one-fifth of California is either abnormally dry or in moderate drought, as of the end of October. It’s abnormally dry in portions of the eastern part of the state south of Lake Tahoe, and in the central Sierra. A strip of land along the Colorado River from about Lake Havasu south to the Mexican border is in moderate drought.

Three months ago, only 4.32% of California was abnormally dry. But that was roughly midway through the dry seven-month period in the state’s Mediterranean climate.

Drought is all in your definition, said Patzert, a retired climatologist from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. Although the reservoirs are generally pretty full, he says he looks at conditions in the wildlands and forests, and after almost no rain for the last seven months, “It’s not just dry, it’s incendiary.”

Falls are likely to be drier because of climate change, Patzert said. And we’re undoubtedly warmer than the average for the last 30 years, but a lot of that is due to suburban sprawl and the urban heat island, he said.

According to the National Weather Service, it was warmer than average in most places in Southern California in October, except in the Antelope Valley. El Niño and La Niña are in neutral this year, but most of the rain in the Los Angeles region comes later in the season, and 60% to 70% of that is borne by atmospheric rivers, which stream moisture from the tropical Pacific into California like a fire hose. “And there are no good predictors for those,” Patzert said.

Atmospheric rivers are sometimes called “Pineapple Expresses” because they’re from the Pacific down around the Hawaiian Islands. They’re always wet, but sometimes they’re warm, causing the snowpack to melt.

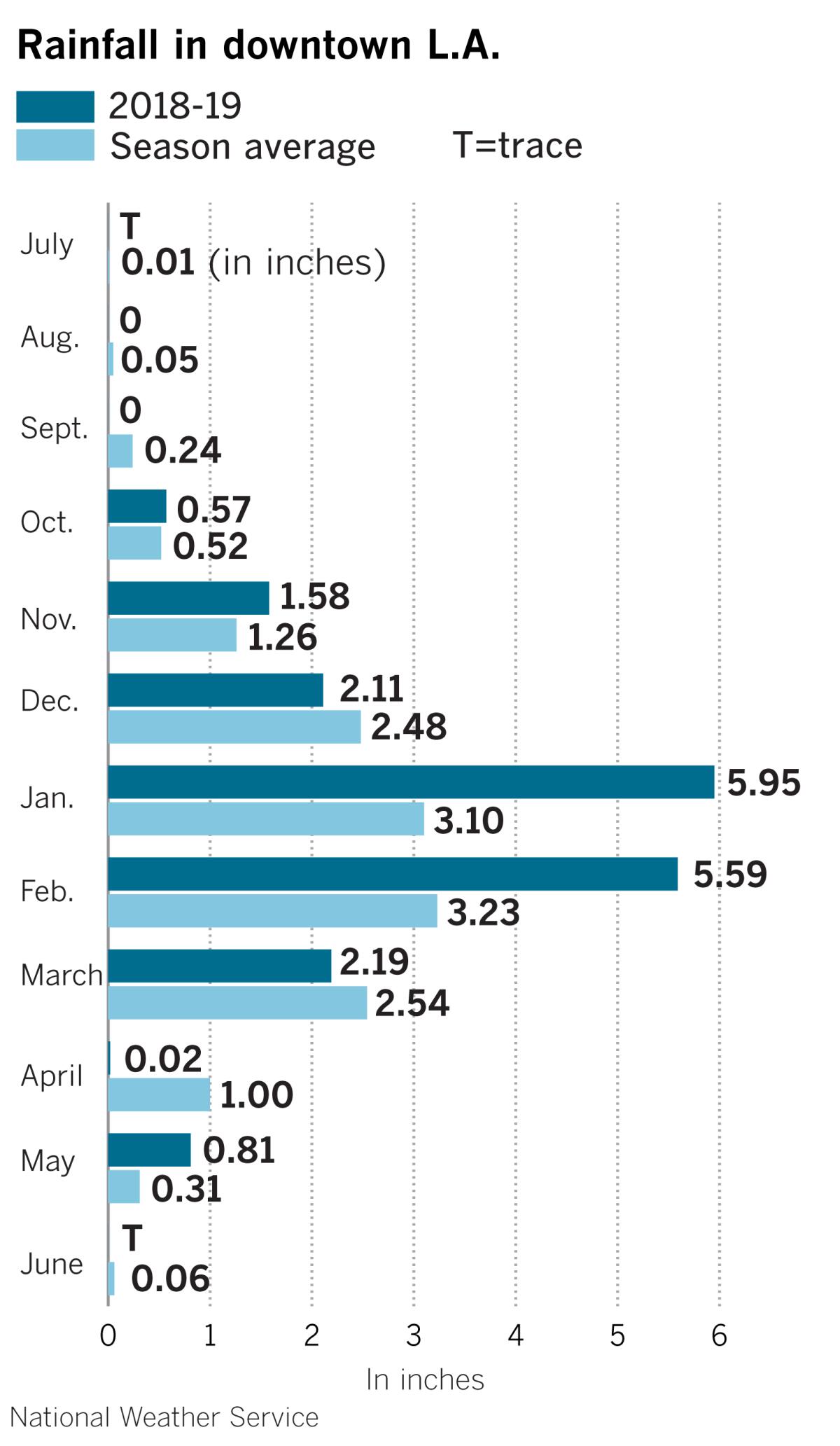

The bulk of L.A.’s rain comes in the months of January, February and March. That was the case in the 2018-19 season, but October was closer to average last season.

Forecasts for November are predicting warmer-than-normal weather in all of California, and drier-than-normal conditions in most of Northern and Central California. It is the northern Sierra Nevada that serves as a water bank for the state, where snow piles up at high elevations through the winter, then gradually melts and replenishes the state’s reservoirs as warmer weather arrives in the high country with the spring and summer months.

This natural storage system can be thrown badly out of whack if warm storms drop rain at high elevations, causing the snowpack to melt too quickly and pose a risk of flooding.

There are many factors in California’s water picture, and it’s too early to call the game, Patzert said, but “it’s the first quarter right now and the Santa Anas are ahead 28-0.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.