Has any California governor dealt with more disasters at once than Gavin Newsom? Not likely

SACRAMENTO — It’s unlikely any previous California governor has faced such a cannonade of calamities — a grand slam of disasters.

All at the same time: power blackouts in both Southern and Northern California, and devastating wildfires at both ends of the state.

It was bad enough with the old normal. For example: Northern California’s devastating wine country fires in October 2017, followed that December by Southern California’s massive Thomas fire in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties.

But four disasters at once?

That’s a governor’s nightmare. A few slip-ups and he might be yanked from office. Google Gray Davis.

So how is rookie Gov. Gavin Newsom doing? How is he performing as he hops around the state meeting with local officials, eyeballing charred ruins, standing before cameras in his official disaster uniform — windbreaker and jeans — and railing against Pacific Gas & Electric Co.?

There’s one thing that hardly anyone — least of all politicians — is talking about publicly. And that’s the inevitability of customers’ monthly bills rising to pay for so-called hardening of the electrical grid to make it less likely to ignite wildfires.

He’s doing pretty well. He hasn’t come across as a grandstander. The uniform fits. He doesn’t seem to be interfering with the real work of firefighting and helping victims.

Newsom keeps pointing the finger at PG&E, where it belongs. The nation’s largest private utility is the main culprit because, as the governor keeps repeating, “for decades, they have placed greed before public safety” by not updating equipment and by allowing flammable vegetation to grow around power lines.

This is not a Gray Davis calamity in the making. In truth, there is very little resemblance between the two governors’ situations — so far, anyway.

Davis was recalled in 2003 largely because he resembled a deer in headlights when the Texas power pirates — Enron, mostly — began holding back electricity in order to drive up the kilowatt price. That resulted in brownouts all over the state and higher profits for the pirates.

Plus, Davis had other PR problems that Newsom doesn’t — a sinking economy that led to budget deficits and his raising the car tax.

Davis was doomed when “Terminator” action hero Arnold Schwarzenegger jumped into the race for governor. Voters love to be entertained.

Newsom is in no immediate political danger. His poll numbers aren’t tumbling as Davis’ did when his energy crisis hit.

In fact, Newsom’s job approval ratings could conceivably climb from their pre-fires position in the mid-40% range.

Newsom scored some invaluable points Tuesday when PG&E reversed itself and agreed to the governor’s request to provide rebates for customers whose power was shut off so wildfires wouldn’t be ignited.

“This is significant because utilities in the past have never credited customers for these disruptions,” Newsom said. He tweeted that the rebates are “the least they can do.”

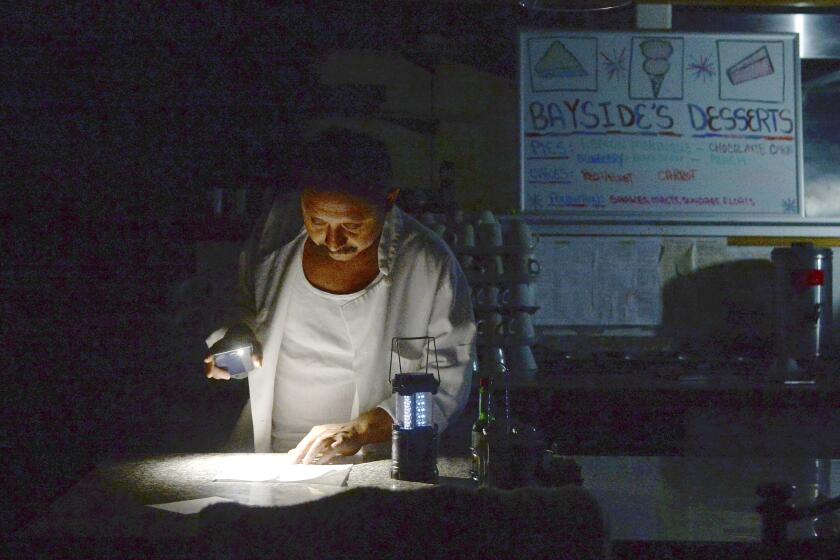

Millions of Californians can do little more than watch as the lights go off, then on and maybe back off again during the blustery autumn of 2019.

“He seems to have been doing a good job,” Republican consultant Rob Stutzman says of the Democratic governor. Stutzman was Schwarzenegger’s chief spokesman during the Davis recall and became his gubernatorial communications director.

“Both ends of the state are on fire and he’s been showing up in both places. He’s acting like a good governor should … saying the right things, thanking the president [for federal aid], staying out of the way.”

“He really has two crises,” Stutzman adds. “The blackouts and the wildfires.”

But is there a danger of a governor showing up at wildfire scenes too often and wearing out his welcome?

“Not as long as the fires are burning,” Stutzman says. “Arnold used to say, ‘Be a man of action!’ Arnold’s instincts were right.

“You only make a mistake if you do something in poor taste. Like when people are running from a fire, you show up in Lakers’ courtside seats. Doing something like that doesn’t sit well.”

But Stutzman adds a caveat: “If power is on and off for weeks on end, we’re no longer living in a first-world nation. I’d be very alarmed. If this happens next year and the year after, that’s when people decide it’s absurd.”

I called Garry South, who was Davis’ chief strategist when he was elected and when he was recalled.

“I think he’s doing well,” South says of Newsom. “More than that, he’s doing the best he can possibly do…. He’s doing a pretty good job of pointing out who the real villain is. And that’s PG&E.

“How can we allow a public utility to essentially say, ‘The only way we can stop ourselves from burning down your house is to shut off the power to your house’? I mean….”

But South thinks the dual dilemma of blackouts and wildfires makes Newsom’s situation potentially “more dangerous” than Davis’ 16 years ago. “Even in our brownouts, we weren’t burning down half the state.”

South believes Newsom should soon make a major speech to explain what he’s doing about blackouts and wildfires. Davis did that about the energy crisis too late, South says. His poll numbers already had plummeted.

Newsom has been doing a lot, along with the Legislature and previous Gov. Jerry Brown.

He has budgeted $1 billion for new planes, helicopters, fire detection cameras — replacing the old mountaintop lookouts — and a lot of other fire fighting and prevention tools. Equipment and crews have been prepositioned to where fires are most likely to erupt. And the state just created its own information hotline and website because PG&E’s haven’t been working.

At one point last weekend, 3 million people were without power in Southern and Northern California, the governor’s office estimates.

Newsom speaks for virtually every Californian when he repeatedly declares that’s unacceptable.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.