Nipsey Hussle was killed next to a school. His death still haunts students

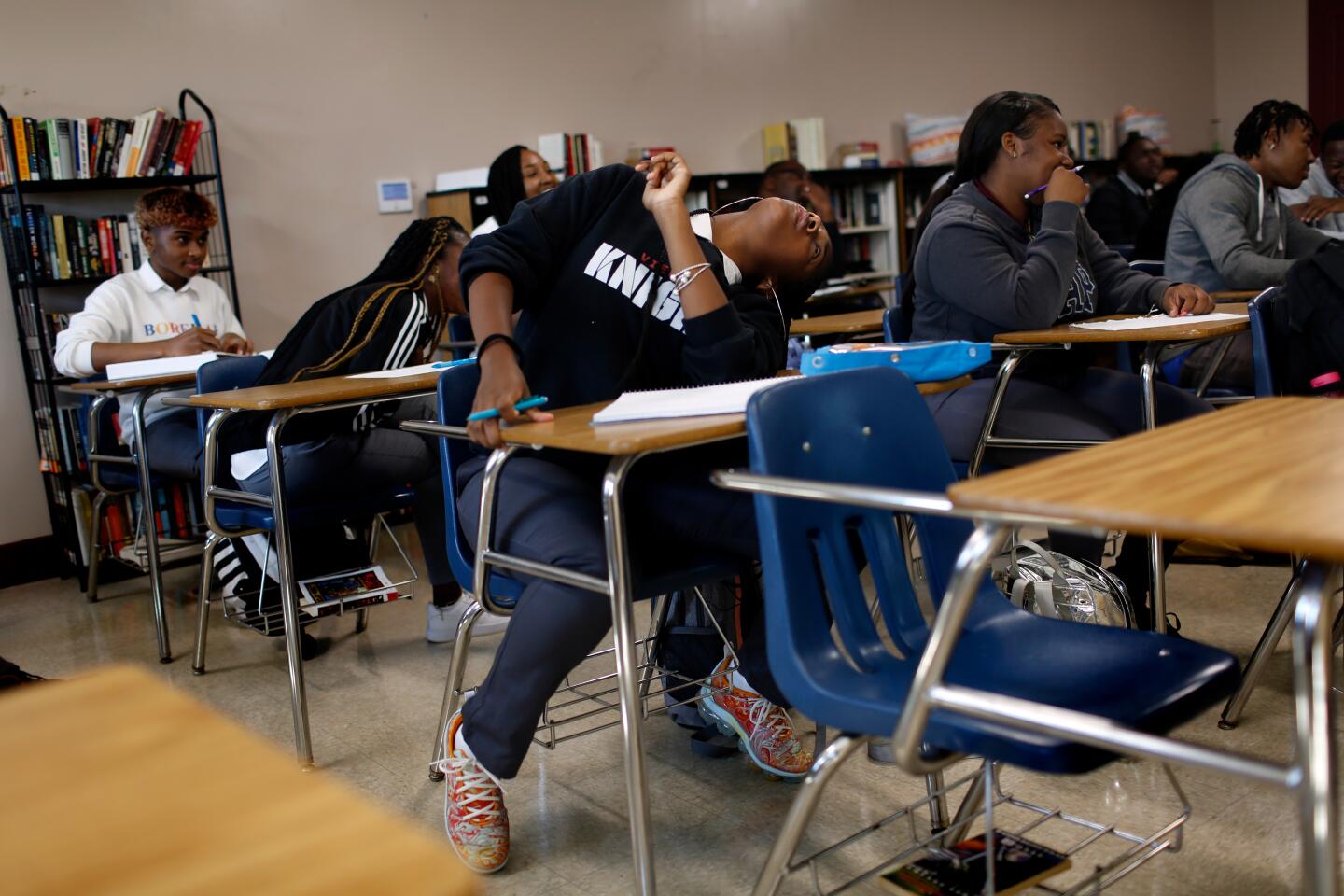

View Park Preparatory Charter High School is across the street from where rapper and activist Nipsey Hussle was shot and killed this year. Kamryn Johnson, a View Park student, says she uses rap to work through the trauma.

Last time that I checc’d / Nipsey came up from the struggle / was our voice, our protector, like a brother

— Kamryn Johnson, 17

Teens around Crenshaw and Slauson know the spot. Across the street from the Marathon Clothing store, through the gates of the high school, up the stairs to the south building balcony. That offers the clearest view of the spot where Nipsey Hussle was fatally wounded.

From the sidewalk, his store and surrounding strip mall are obscured by a new perimeter fence swathed in green mesh like a construction site, keeping out visitors and gawkers.

But from the balcony at View Park Preparatory Charter High School, students can see everything. They used to sit atop the balcony stairs, hoping to spot Hussle’s car in the parking lot, then hop over to the store or Hungry Harold’s to say hello to the rapper and business owner.

When their principal, Charles Lemle, heard gunshots while he happened to be working on a Sunday afternoon in March, he rushed up the stairs of the south building. He stood just inside the balcony doors and watched paramedics wheel away someone — either Hussle or another man who was shot.

In the days after Nipsey Hussle was killed, The Times talked to people to learn how they were affected by the rapper’s death. A teacher at View Park Prep spoke up on behalf of his students.

The teens who came to school the next day, and the day after that, and the weeks after that, would eat lunch on those balcony stairs, watching the hordes of mourning fans pose for a picture, then leave. Hussle’s music blared from the procession of cars, a constant soundtrack of lyrics and beats rising to their balcony perch.

Now, with a new school year, some students avoid the balcony. Routes to campus changed after the killing to avoid the Marathon Clothing site. Some parents and students still avoid it. So-called safe passage community workers spend more time on the streets closest to the store, which became busier after the shooting.

Teachers are trying to figure out how to acknowledge the anguish students felt about all that has unfolded across the street, without invoking Nipsey fatigue. And while some students grieve silently, some are more vocal. One has taken to song.

Dealing with their mortality

Last time that I checc’d / the Marathon it keep on goin’ / and the hussle yeah it keep on growin’

Yeah they hate to see our unity / but they ain’t know that it been showin’ / and our melanin yeah it been glowin’

In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, many students felt a sense of hopelessness, said Ebony Curtis, the school’s counselor. If Nipsey couldn’t make it, how could they? Summer, however, gave students a break from the Nipsey barrage, a chance to think about the effects of his death on their own terms, she said.

Kamryn Johnson, a senior, returned to school cognizant of her own mortality — and with new resolve.

“Who knows? I might not even wake up tomorrow,” Kamryn said, “so I want to at least say I at least attempted to achieve my goals before I pass.”

To Kamryn, Hussle embodied what is possible through drive and hard work, someone from the community who found success in music and reinvested in the community that raised him. In her bedroom, she covered a whiteboard with quotes from his songs to keep her going. “I went through every emotion with tryna pursue what I’m doing,” she wrote in red, a blue heart interrupting the lyrics.

She wants to be a musician and choreographer, and she now devotes most of her time outside class to those goals. She was a dance team captain last year, and this year she is taking practice even more seriously, her coach said. She attends a dance academy in the evenings.

After school on the blacktop of the gated campus, Kamryn’s dedication is on full display. She leads the dance team through stretches and patiently demonstrates the eight-count moves they need to perfect for football games. Her face is serious, her voice authoritative.

“She’s matured so much,” her coach Sherrell Bryant said.

Kamryn was used to seeing Hussle a few times a week at Hungry Harold’s, a popular spot close to the Marathon Clothing store and the school. She wanted a photo with him, but she never asked — she was often sweaty from dance practice, and she figured she’d see him again soon anyway.

She said she still feels a jolt at some point every day, sometimes triggered by the newly painted murals of the slain artist near her school, sometimes by the fencing that cordons off his store.

A survey of students and parents in the spring showed that they felt less safe at the school than they did the year before. Decades of research suggest that the effects of exposure to violence on teenagers are wide-ranging and can result in anxiety, depression, anger, absences and an inability to concentrate in class. A recent Times analysis found that from 2014 to 2018, 36 people were killed within a mile radius of the View Park campus.

Many students can name someone close to them whom they’ve lost unexpectedly and violently, and they have not had the tools or attention to process those traumas, said Assistant Principal Michael Farber. So each new loss is a trigger.

“Once we have that experience, if anytime in the future, something reactivates that experience, it’s as if we’re right back in that initial trauma,” Farber said. “So for many of our students … they haven’t had the support, the guidance and the ability to manage through some of their trauma and triggers.”

As Curtis, the counselor, put it: “This is history for them. Just coming to school every day, you’re going to pass by the store…. I think that it’s always going to be on their mind.”

Since Hussle’s death, View Park educators have hastened plans to address students’ mental health. At weekly circles, students can talk about their feelings, learn how racism affects health and discuss articles on mindfulness and depression in black youth. A plan to open a wellness center now feels more urgent.

View Park, founded about two decades ago, draws its 500 students from the nearby area, including Compton and Inglewood, and is part of the Inner City Education Foundation, one the first charter networks in Los Angeles. Today, the high school’s student population is 97% black, and 7 out of 10 students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches.

View Park’s class of 2018 had an 87% graduation rate, and 54% met California State University entrance requirements. State test scores from spring 2019 showed that on 11th-grade state standardized tests, 41% of students met English language standards and only 6% met math standards — so time is built into the day for extra help and interventions.

The complex conditions that lead to these outcomes — where only 1 in 17 juniors can do math at grade level — embody the kind of inequities that Hussle fought against as many students grapple with poverty and traumas like Hussle’s death.

Hussle had ties to the school — his sister was a former student, and he was friendly with students who visited his store or ran into him in the neighborhood. He would ask them about their grades.

Some parents choose the school in part for its sense of community; they wanted their teenagers to be educated among people who look like them, where they can learn and thrive. The school emphasizes character principles that make up the acronym “RIDER” — respect, integrity, discipline, effort and responsibility.

Now, Nipsey Hussle is part of that lesson.

Finding solace in music

Nipsey Hussle made me proud to call myself black and then / y’all come and take his life ain’t that some shhh

Last time that I checc’d / you supposed to treat a legend with respect / not shoot ’em five times in they chest

Students gravitated to Sebastien Elkouby’s class after the killing. He teaches a music production elective and a class on global awareness through hip-hop culture. One corner of his classroom has been turned into a small studio, and the walls are plastered with posters of hip-hop legends.

Hussle has always been on Elkouby’s syllabus; students discussed his entrepreneurship and activism. But some students felt overwhelmed after the shooting, Elkouby said. In the opening weeks of class this semester, he has let students be the first to bring up Hussle — and they do.

“They used him as an example of what happens when your personal empowerment or your desire to grow and better yourself expands beyond your immediate circle, your family or friends,” Elkouby said. “What kind of impact does that have? Once you’ve empowered yourself, how can you empower others? So, of course Nipsey came up because they felt like, well, this is what he did.”

Even for the few students who weren’t familiar with Hussle, his death has had a lasting consequence.

Linsey Montgomery used to walk to school. But after the killing, amid rumors of gang retaliations and social media posts that made it hard to parse real threats from false, her parents began to drive her. Linsey, 17, listens to more rock and alternative music than anything else. She found it disconcerting to be on a campus where so many were mourning for so long.

But now, as a visual artist, she appreciates the Hussle murals. Her first assignment in AP government class was to find three sources and write about how Hussle embodied the school’s character principles. She liked learning about someone’s place in her city beyond his gang affiliation.

Safety is less of a concern now than it was in the spring, she said, but a week into the school year, her parents still dropped her off and she didn’t walk alone after 5 p.m.

Kamryn Johnson’s tribute

The day after Hussle was killed, Kamryn rewrote one of his songs to express her grief.

At a school tribute the week after Hussle’s death, Kamryn stood in the View Park courtyard before her classmates, in front of a poster that Linsey had drawn of Hussle in profile with the words “RIP NIP.” She rapped the hook and then mostly her own lyrics to his track “Last Time That I Checc’d,” a song about his success as a rapper and business owner, his legacy and the importance of owning one’s business and products.

With the start of senior year, Kamryn has her sights set on a music and business major in college. At school, she is intent on moving past the dark feelings. That’s why she avoids the view from the balcony.

Nip, you gone but your dream is still livin’

Last time that he checc’d / it was no dirt on his rep /got the money and the power and respect

Last time that he checc’d

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.