Operation Gatekeeper at 25: Look back at the turning point that transformed the border

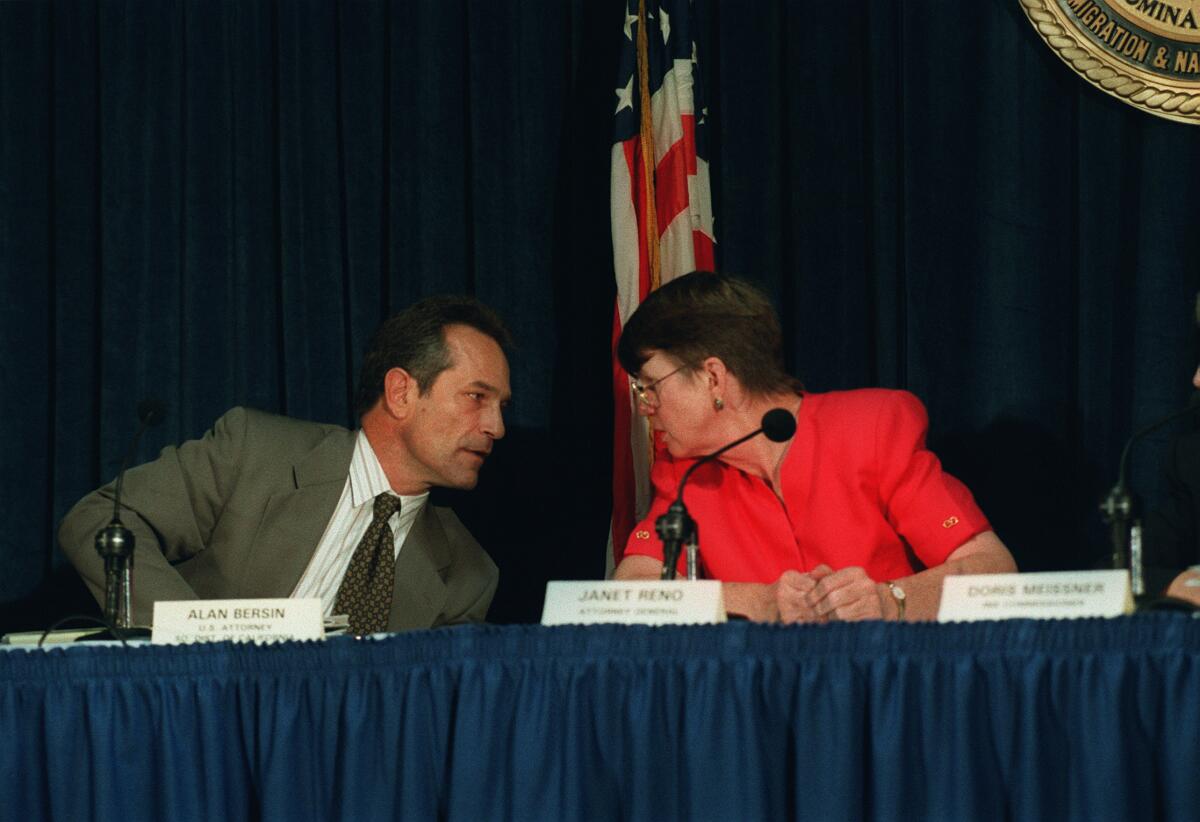

SAN DIEGO — Atty. Gen. Janet Reno wanted to see the chaos for herself.

She watched as hundreds of migrants gathered in the dusk along the northern edge of Tijuana, waiting for darkness to make the illegal journey into San Diego.

The border fencing that had been erected over the last few years wasn’t about to stop them.

She turned to the San Diego sector’s chief patrol agent and asked what he needed to control the border. Sensors, radios, vehicles, more agents, he said.

She told him to put together a plan to make it happen.

What emerged was a whole new approach to border enforcement.

Operation Gatekeeper was unveiled on Oct. 1, 1994. The strategy was to deter migrants from illegally crossing in the first place — and, for those who remained undeterred, to encourage them to cross in more isolated wilderness areas to the east, where they could be more easily captured.

Twenty-five years later, Operation Gatekeeper is still viewed as a major turning point in the effort to control the border.

It is considered both a success and a failure, depending on whom you ask.

One thing is certain: Operation Gatekeeper set in motion a process that significantly altered the landscape of the U.S.-Mexico border and transformed San Diego into one of the most heavily fortified international boundaries in the nation. It also came with a human toll, as migration shifted to the east.

Pre-Gatekeeper

“The border was nothing like it is now,” observed photojournalist Don Bartletti.

His fascination with the border began as a staff photographer with the San Diego Union in the late 1970s, “when the border was essentially a cable or strands of barbed wire smashed into the dirt by thousands of feet coming north.”

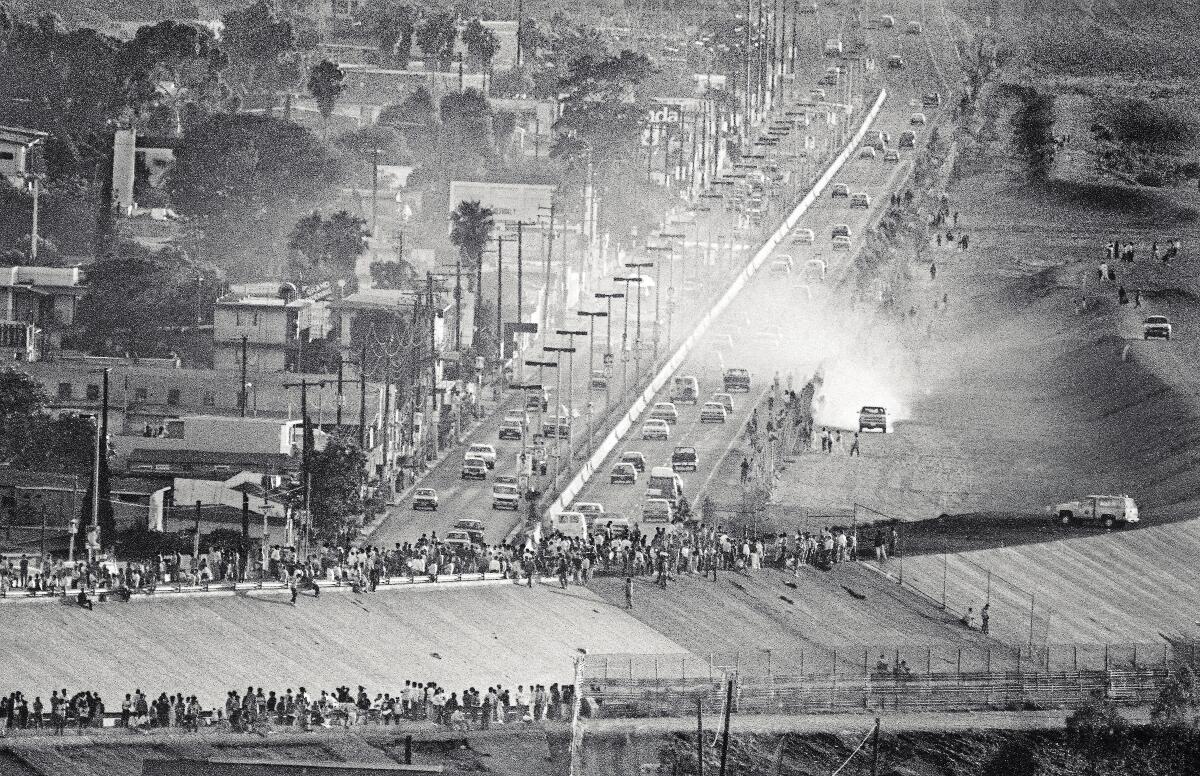

He recalled the masses of migrants who gathered nightly at a popular staging spot near Tijuana’s Colonia Libertad known as “the soccer field.” Vendors would sell food and provisions for the journey. Catholic priests would hold Mass. Smugglers would connect with customers.

The crossers far outnumbered the Border Patrol agents on the other side.

Then, in waves over the next several hours, the crossers would go for it. They ran through brush and canyons — which were often teeming with bandits waiting for their prey — and followed roads so they could melt into the city. It was not uncommon to see unauthorized immigrants dash across Interstate 5, with tragic results.

The same thing was happening farther west at Border Field State Park, where an obelisk and a 6-foot-high schoolyard chain link fence marked the international boundary.

“Quite often, it was bending so far over that people waiting for nightfall would use it as a hammock,” Bartletti recalled of the fence.

That stretch of land — the first 7.5 miles beginning at the Pacific Ocean — became the busiest corridor for illegal crossings in the country.

“Many nights, we were catching hundreds, if not thousands, of people a day,” recalled Assistant Patrol Chief Chancy Arnold, who started as a rookie agent in 1985. Sometimes he’d end up capturing the same group a few times in the same night.

“It was a little demoralizing to go out there and to see the amount of activity and know we didn’t have the adequate amount of resources to actually control it,” Arnold said. “It’s like, ‘What am I doing here?’ You see thousands of people getting past you.”

A more substantial fence started going up around 1990. It was made of helicopter landing mat leftover from the Vietnam War.

It managed to cut down the number of vehicle loads that’d blow through, but it was easily breached by those on foot.

Torches and saws cut through the metal. Whole families — including women in kitchen dresses, girls in dress shoes and even seniors — were often seen scaling the new barrier, its horizontal corrugated slats essentially serving as a ladder.

“The fence didn’t stop anybody,” said Bartletti, who continued photographing the border for the Los Angeles Times.

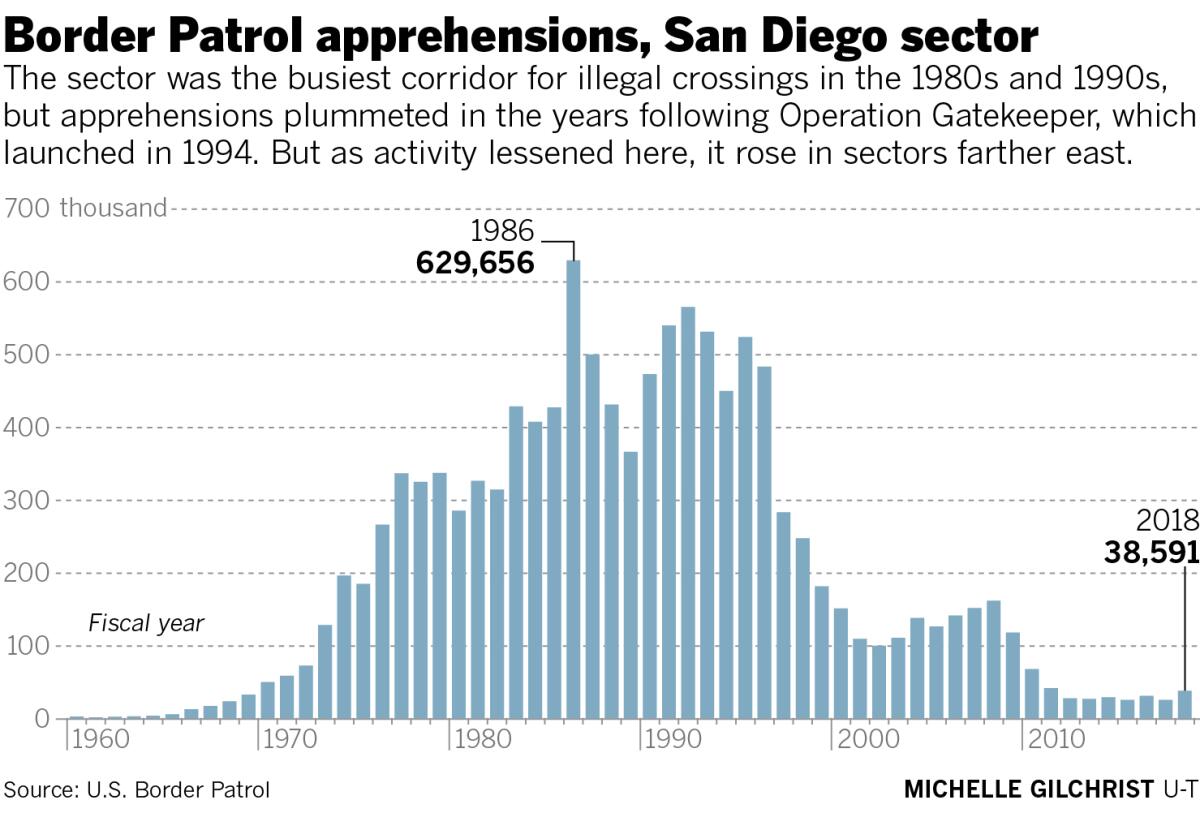

By fiscal 1993, the San Diego sector accounted for 42% of all apprehensions along the southwest border. The 531,689 people caught that year likely represented only a fraction of those who crossed unhindered.

A new tactic

The atmosphere was ripe for Operation Gatekeeper.

California Gov. Pete Wilson was fighting to be reelected. Already a loud voice blaming Washington for doing nothing to stem the flow of illegal immigration — and leaving the state to pay for the costs — Wilson got louder during his campaign. He became an outspoken champion of Proposition 187, a ballot measure that cut off state services such as healthcare and public education to unauthorized immigrants.

An influx of labor-related migration was also anticipated with the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994.

At the same time, an experiment in El Paso — a city with a similar urban-border interface — was seeing some results. Operation Hold the Line, started in October 1993, shifted the bulk of agents to the city’s downtown area, where they’d hold positions in sight of one another and potential crossers. The number of apprehensions dropped by 70%, according to a report by the U.S. office of the inspector general.

Immigration issues were also getting more attention from Congress, with $1.2 billion allocated for “border control, criminal alien deportations, asylum reform and a criminal alien tracking center” as part of the wide-ranging Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994.

“This is one of the most difficult issues facing America,” Reno told a crowd of reporters following her tour of the border in August of 1993.

Gatekeeper soon began to crystallize.

The strategy was similar to that in El Paso, asking agents to hold the line in fixed positions and in three layers. The first visible layer would largely deter illegal crossings, and the next two layers would catch those who did cross and made it past the first.

The tactic was a departure from how agents had usually operated, patrolling wide swaths of border as they saw fit. The chases and high number of apprehensions were part of what made the job exciting to many agents.

But now, the measure of success would be low apprehension figures, not high.

The strategy required many more agents, both new hires and redeployed agents borrowed from other areas. The sector was given new rugged vehicles, seismic sensors and radios. New night scopes attached to the top of agents’ Ford Broncos got the nickname “el búho” — the owl — from Mexicans.

Rather than focus on the entire San Diego sector at once, Gatekeeper started in the most southwestern corner of the U.S., under the control of the Imperial Beach station, which was by far the busiest corridor. Once that strip was under control, then the operation would move farther east until the whole sector was sewn up.

By doing so, Gatekeeper would intentionally cause crossing routes to shift farther east to California’s mountains and deserts, where authorities figured migrants would be more easily detected and caught.

Gatekeeper rollout

The difference between pre- and post-Gatekeeper was striking.

“I remember going out on patrol one night in an area were there would normally only be one or two agents working and be amazed,” Arnold recalled. “Everywhere I looked I could see a vehicle parked, not only along the border but also farther north. I was amazed at how many agents were out.”

Apprehensions ticked up at the very beginning of Gatekeeper as expected, then dropped steadily in San Diego over the next several years.

From fiscal 1992 to 2004, overall apprehensions in the sector declined by 76%, according to Border Patrol data.

Conversely, Border Patrol staffing in San Diego grew, from about 1,000 to 1,650 in the same period.

Rep. Bob Filner testified to Congress in 1996 that he was at first skeptical of Gatekeeper’s impact, but he said his constituents had changed his mind.

“People whom I represent, who live in communities right here near the border, have felt a very radical change in their own living conditions. That is, they have felt safer,” Filner said. “They have not seen the scores of people coming down the streets or in their backyards. They are opening up their garages.”

Alan Bersin helped launch Gatekeeper as U.S. attorney in San Diego, and he was named the so-called “border czar” by President Bill Clinton a few years later to implement the strategy across the rest of the southwest border.

“Neither side claims it, but Gatekeeper was probably the most important domestic achievement accomplished in a purely bipartisan manner through three administrations, and the greatest accomplishment since President Eisenhower and the Democrats put together the state highway system in the mid-1950s,” Bursin reflected.

With Gatekeeper came a new system to fingerprint migrants as they were apprehended and processed. With firm identification, repeat crossers could be identified and charged with illegal reentry, a felony. The number of prosecutions jumped to nearly 4,000 annually in the mid-’90s, Bersin said.

Gatekeeper ushered in a number of other border initiatives. Among them was the construction of a secondary mesh metal fence along the first 14 miles of San Diego’s border with Mexico beginning in 1996, further slowing illegal crossings.

Deadly consequences

With Gatekeeper came a high human cost.

As expected, migration shifted farther east, into inhospitable environments that have claimed many lives.

Traffic was eventually funneled into Arizona by the 2000s, as El Paso also ramped up enforcement to the east.

The bottleneck is evident in the data. While San Diego sector apprehensions plummeted, the Tucson sector saw apprehensions increase by 591% between fiscal 1992 and 2004, according to Border Patrol data.

“One unintended consequence of this enforcement posture and the shift in migration patterns has been an increase in the number of migrant deaths each year; on average 200 migrants died each year in the early 1990s, compared with 472 migrant deaths in 2005,” according to a 2009 report by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service.

Various estimates put the number of border-related deaths anywhere from 7,500 to 12,000 since 1998.

“We’ve never had a public accounting for that,” said Everard Meade, director of the Trans-Border Institute at the University of San Diego. “That’s never been front or center of the policy discussions.”

Gatekeeper was instrumental in providing the impression that the border was under control when what it actually did was shift illegal crossings farther out of sight of city dwellers, said Pedro Rios, director of American Friends Service Committee’s U.S.-Mexico Border Program.

“From a human rights vantage point,” Rios said, “it was an utter failure.”

The operation had other long-lasting byproducts, according to academics. Gatekeeper made crossing the border illegally a much riskier, more expensive affair, driving mom-and-pop smugglers out of the picture as more organized-crime networks jockeyed for profits, said Rios.

It also prevented migrant workers from regularly traveling back and forth across the border. Rather than risk being apprehended, the family breadwinners would stay in the U.S., and their families back home would often migrate to the U.S. too, experts said.

“It brought a more permanent undocumented population to the U.S.,” said Meade.

Then and now

These days, the human chain of agents along the border in San Diego has long been replaced with a mixture of roaming patrols and fixed observation points. The strengthened border wall, combined with a vast network of cameras, sensors and stadium lighting, does a lot of the work.

Arnold, who is the most veteran Border Patrol agent in the nation with nearly 35 years of service, described Gatekeeper’s legacy this way: “It was the defining moment that helped us get to the point we are today in our border security mission, using the right mixture of personnel, technology and infrastructure.”

Notably, the framing of the immigration debate raging today should not be one of border security, but of a broken asylum system, Bersin argued.

“The people coming up now are not trying to get away from Border Patrol,” he said, “they’re trying to surrender to them.”

The historical perspective is sometimes lost on newer agents in San Diego, who hear the pre-Gatekeeper stories but don’t fully grasp the transformation.

So the Border Patrol asked Bartletti to show them. The now-retired photographer selected four iconic images of mass migration — crowds taking Mass at the soccer field, hundreds staging at the Tijuana River levee. Then he shot images in the same exact spots as they appear now — empty landscapes of concrete and metal.

The before-and-after images will hang in the chief’s conference room in the sector headquarters in Chula Vista.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.