Dr. Bob Sears’ views on vaccines have inspired loyal followers — and a crush of criticism

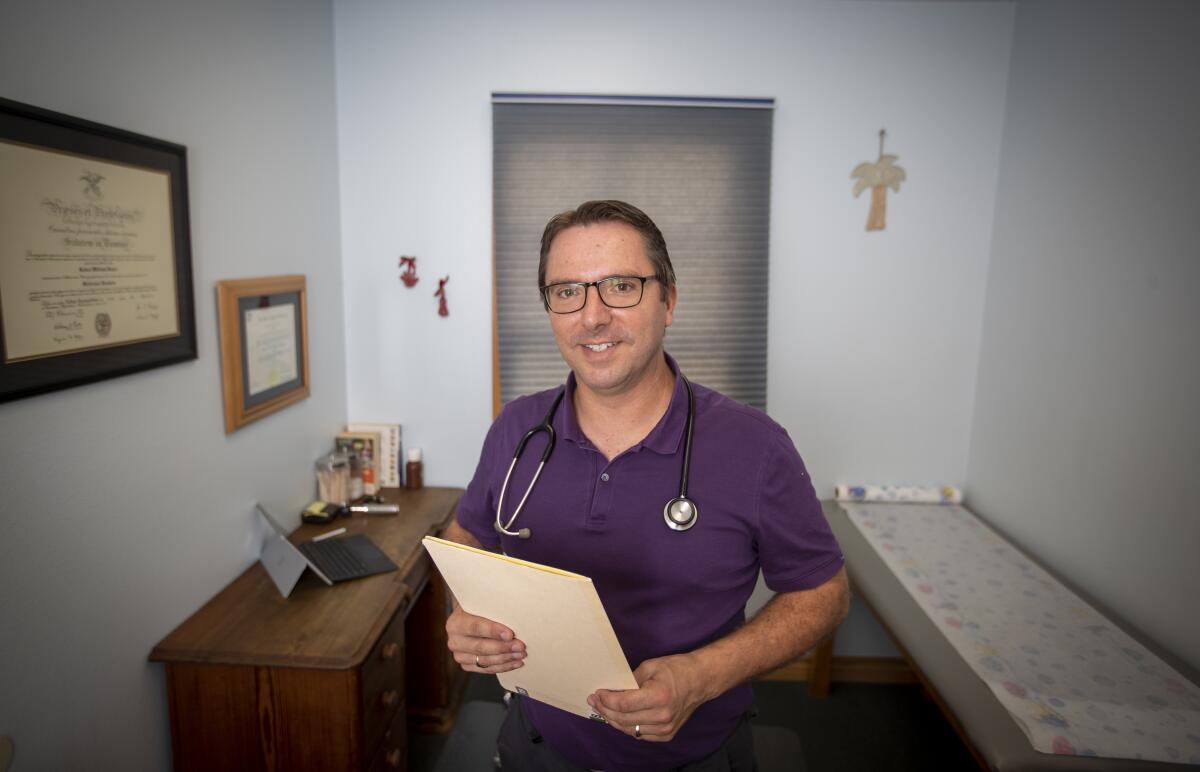

Dr. Bob Sears sits at a worn wooden desk near a cushioned exam table designed for pediatric patients. The room has only a few other trappings — small molds of a child’s foot and hand, hanging from a wall — that suggest the routines of childhood. And there is nothing to suggest the notoriety that trails in his wake.

But this office is a hub in a nationwide movement that the medical establishment contends is a threat to public health. Sears’ practice caters to parents the public largely labels as anti-vaxxers, people who no longer trust the scientists, doctors or government representatives who say vaccines are safe and that the risk of disease is far greater than the chance of an adverse reaction.

Parents travel from across the state to Sears’ family practice in affluent Capistrano Beach, all of them paying out of pocket for checkups. Some of them believe that vaccines caused a sudden allergic reaction or neurological change in their children; others question whether they should delay the standard vaccination schedule — or ignore it altogether.

Sears gives these parents something they desperately crave — a kind smile and an acknowledgment that it’s OK for them to trust their intuition.

His patients, and even some of the parents, affectionately call him Dr. Bob, a formality-stripped name modeled after his well-known pediatrician father, Dr. Bill. But outside the welcoming confines of his office, Sears is referred to with a wide range of adjectives.

He is resolute or reckless. He’s reassuring or fear-mongering.

Amid a measles outbreak afflicting nearly 1,200 people nationwide and the uproar surrounding a controversial bill to strengthen the state’s school vaccination laws, it’s unlikely you’ll find middle ground between the extremes.

He’s either Dr. Bob or, as some of his critics claim, a dangerous doctor.

::

[W]hat he has done is sow a little seed of doubt. He led people down a path of fear.

— Erica DeWald, director of advocacy of Vaccinate Your Family

The Sears seal of approval goes a long way in the world of pediatrics.

Patriarch Dr. Bill Sears is a well-known author of parenting books, most notably “The Baby Book,” a hugely successful and influential guide promoting attachment-parenting, in which mothers are encouraged to breast-feed their children past toddler-hood, parents are urged to hold their children as much as possible, and co-sleeping is promoted for supposed health and behavior benefits.

Martha Sears, Bill’s wife and Bob’s mother, is a nurse and coauthor of many of the four dozen parenting books written by various family members. Three of Bill and Martha’s children are physicians: Jim Sears, who was on the daytime talk show “The Doctors,” practices with his father in the Capistrano Beach building that also houses Bob Sears’ solo practice. Peter Sears is a family practice physician in Tennessee, and other siblings work in conjunction with the family’s many health-related businesses.

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from Los Angeles Times.

The Sears health empire also includes public speaking events, a wellness institute that offers paid courses to become a “health coach,” product endorsements for nutritional supplements and baby products and the “Dr. Sears Family Podcast.”

Among the most controversial of the family’s endeavors is Dr. Bob’s bestseller “The Vaccine Book: Making the Right Decision for Your Child,” first published in 2007. In the book, Sears, who was first licensed to practice medicine in 1996, writes that parents who are leery about the number of shots their children receive in their first two years of life have more choices than most pediatricians offer.

Get the shots. Delay the shots. Or simply skip the shots. Just know the risks and make a decision that’s right for your family, Sears wrote. His mantra: It all comes down to parental choice.

“Every other vaccine book either gives you all the negatives about vaccines and tells you not to do them, or it gives you only the positives, with a little asterisk footnote about the negatives,” Sears said during an interview. “My book was the first neutral one, and [it] allowed parents to kind of formulate their own decisions.”

The book offers an alternative schedule to vaccination, which, Sears argues, could decrease the likelihood that a baby’s immune system is overloaded. Sears contends there is not enough research on the long-term effects of the schedule recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He acknowledges, however, there is no medical research indicating his own schedule is safer.

Medical and public health officials have lambasted Sears’ approach to vaccines, which are widely acknowledged to be one of the most important medical developments of the 20th century. They say that delaying shots leaves children unprotected from diseases longer than is necessary — with no proven benefit.

“He’s a doctor from a very reputable family who questioned vaccines in a gentle way at first,” said Erica DeWald, director of advocacy of Vaccinate Your Family, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group. “But what he has done is sow a little seed of doubt. He led people down a path of fear.”

Sears said that at first, his father discouraged him from writing a book on vaccines, saying it was too controversial, but added that he “has come around now to pretty much agreeing with most of my ideas.” His brother Jim, Sears said, “semi-agrees quietly.”

Jim Sears said it can be difficult to see his brother cast as dangerous or self-serving. He said Bob is research-driven, often highlighting the latest study on general pediatric care and leaving it on Jim’s desk.

“I’m a little more sensitive to public opinion than him,” said Jim Sears, who is two years older than Bob but notes that his younger brother managed to finish medical school first. “He doesn’t care what people think.”

Jim Sears, who focuses on nutrition and weight loss, said it can be uncomfortable when someone approaches him at a public speaking event and confuses him for the vaccine book author.

“I have to correct them that I’m the TV doctor,” he said with a laugh.

In November, Bob Sears, who is 50, launched “The Vaccine Conversation” podcast with his business partner, Melissa Floyd, with episodes titled “The REAL Reason We Are Seeing More Measles,” “Censorship: Are the Vaccine Thought Police Finally Here?” and “Do Vaccines Actually Make You Healthier?”

“To me, vaccines are not simple,” Sears said in the first episode of the podcast. “Everyone looks at them like you go to your checkup, you get all your shots and you go home and everything is fine. ... I know from 20 years of pediatrics [and] giving vaccines in my office, it is the single most complicated medical intervention your child will ever receive in his or her entire life.”

The podcast has been downloaded nearly 400,000 times in 92 countries, according to analytic data Floyd shared with The Times.

“It just shows you how many people really want to have this conversation,” said Floyd, who said her daughter suffered seizures after being vaccinated.

Sears said the podcast is needed because most doctors are unwilling to talk about vaccine side-effects out of a concern that doing so will lead to parents opting out. But, that’s not how Dorit Reiss, a law professor at the UC Hastings College of Law who studies vaccine policies, sees it.

The podcasts “repeat anti-vaccine talking points, overstate vaccine risks and understate the benefits,” Reiss said. “They are not a good source of scientific information. “

On the other hand, the online reviews of the podcast are glowing.

“I definitely admire Dr. Bob for sticking his neck out there in the medical community,” a reviewer wrote in June. “Truly, all he is doing is standing up for what is true and evidence based. ... I’m forever grateful for each and every podcast. It validates everything I’ve already researched.”

::

At the start of a lengthy interview in his office last month, Sears introduced himself with a firm handshake, holding it just a little longer than expected. He had been somewhat reluctant to agree to the conversation, avoiding eye contact at the start, but he also wanted, he said, to set the record straight.

The media has gotten so much wrong about him and the debate over vaccines, he added. “They’re now a tool of the government to get agendas out there. And, they are no longer fairly serving the people the way they should be as a neutral entity.”

After talking for four hours, Sears remained as apprehensive and stiff as he appeared at the beginning of the interview. But that’s not the demeanor that parents and children typically encounter when they come to his office, run into him at the grocery store or shake his hand before a hearing in Sacramento. In those settings, he is engaging, smiling often. During checkups, moms say, he makes small talk with children in a high-pitched voice to soothe them, and he lets parents rattle off questions until they run out of things to ask.

“He genuinely cares about children,” said Christina Mecklenburg, an Orange County mother who started seeing Sears after her 1-year-old was diagnosed with ocular palsy, a condition in which the eyes become crossed, five days after receiving a vaccine. Ocular palsy is listed by the vaccine manufacturer as a possible rare side effect. Four pediatric neurologists wrote that the girl’s condition was probably triggered by the vaccine, according to medical records shared by Mecklenburg, but the girl’s own pediatrician did not believe there was a link. So Mecklenburg said she started going to Sears.

“He understands the importance of informed consent about vaccinations,” she said. “He never says he doesn’t believe in vaccinations. He says you need to read the consent form and here are the things you should know before you vaccinate.”

Although he is called an anti-vax doctor, Sears does not consider himself anti-vaccine, and pointed out that he routinely immunizes children in his office. But his practice consists primarily of parents who avoid shots, he said.

“None of my patients have even asked for the full CDC schedule [of vaccines] here,” Sears said. “That’s probably why they come to me ... they know I won’t push it on them.”

Infectious disease expert Dr. Paul Offit has a different take on Sears.

“I think he’s dangerous,” said Offit, a pediatrician based in Philadelphia and co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine.

Offit said Sears overstates risks and links vaccines to conditions without an adequate scientific basis. Sears, Offit said, points parents to what are known as “package inserts,” which are legal disclaimers detailing any medical issues reported after a vaccine is administered during pre-license trials, even if the side effects occur at the same rate as the placebo group.

“He adds to this game of whack-a-mole, where we are constantly having to put down uninformed claims,” Offit said.

Much of the conversation about so-called vaccine injuries involves the MMR vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella, and whether it can cause autism. Offit is direct in his words: “It does not.”

Sears isn’t as certain.

(Dr. Paul Offit) is right, the studies don’t demonstrate a link. But he likes to conclude we know vaccines don’t cause autism and I like to conclude that we don’t know yet.

— Dr. Bob Sears

During the interview in his office, Sears said the vaccine can cause brain injuries and autoimmune diseases, making it “biologically plausible” that there is a link to autism. He added that research has neither proved nor disproved that vaccines can be attributed to an increase in autism rates. (Experts say the increase can be tied, in part, to greater awareness and changes in diagnostic criteria.)

Such assertions of a link, which stem from a now discredited paper co-written by Andrew Wakefield, a former British doctor, in 1998, have been widely refuted.

Offit said Sears uses language that incites fear, telling parents that science has yet to prove that vaccines don’t cause autism when there is no reason to believe that they do.

“You can never prove never ... it’s not the way the scientific method is constructed,” Offit said. “So, [scientifically speaking] we can’t say MMR doesn’t cause autism, even though 18 studies in seven countries involving hundreds of thousands of children shows you are at no greater risk of getting autism if you got that vaccine or didn’t. People like Bob Sears take advantage of the fact that science can’t be definitive.”

Sears contends that Offit is stretching the limits of science.

“He’s right, the studies don’t demonstrate a link,” Sears said. “But he likes to conclude we know vaccines don’t cause autism and I like to conclude that we don’t know yet.”

Public health officials say the language surrounding vaccine safety is critical. This year, for the first time, the World Health Organization named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 global health threats.

In the United States, debilitating, deadly and incredibly contagious diseases have been nearly eliminated by vaccines. But to keep polio, measles, whooping cough and other illnesses at bay, public officials say that a high percentage of the population must be vaccinated. Opting out, those experts warn, should be limited to only those who can’t be safely vaccinated, including babies too young to be inoculated against certain diseases or children with medical conditions such as cancer.

Offit said Sears’ book helped spread anxiety about vaccinations that has led to outbreaks of measles, including a cluster of cases in 2008 in San Diego. Patient Zero in that outbreak was a 7-year-old boy returning from Switzerland. That boy was reportedly Sears’ patient. Sears did not confirm or deny that when asked.

However, Sears is quick to fire back at allegations that he’s to blame for any outbreak in recent years. It’s the parents of his patients who make the decision on whether to vaccinate, he said. He is simply a doctor willing to talk about the potential side effects, he argues.

“I don’t think any doctor could ever raise their hand and say they’ve never had a patient who has caught a vaccine-preventable disease,” Sears said.

Sears is under investigation by the Medical Board of California for vaccine exemptions he wrote in 2016. That investigation, which was announced in June, comes as Sears is currently on a 35-month probation issued by the medical board, which charged Sears with committing gross negligence after he wrote a letter in a court case siding with the mother of a 2-year-old boy who did not want her child to receive any more vaccines over the objections of the father.

The mother in that 2014 case said her son went limp and couldn’t pass urine or stools after receiving shots at another doctor’s office. Sears said the judge in the case upheld his opinion, but the medical board said Sears failed to obtain “basic information necessary” to determine if the child should skip all future vaccines. Sears settled the case by accepting the probation, but did not admit wrongdoing.

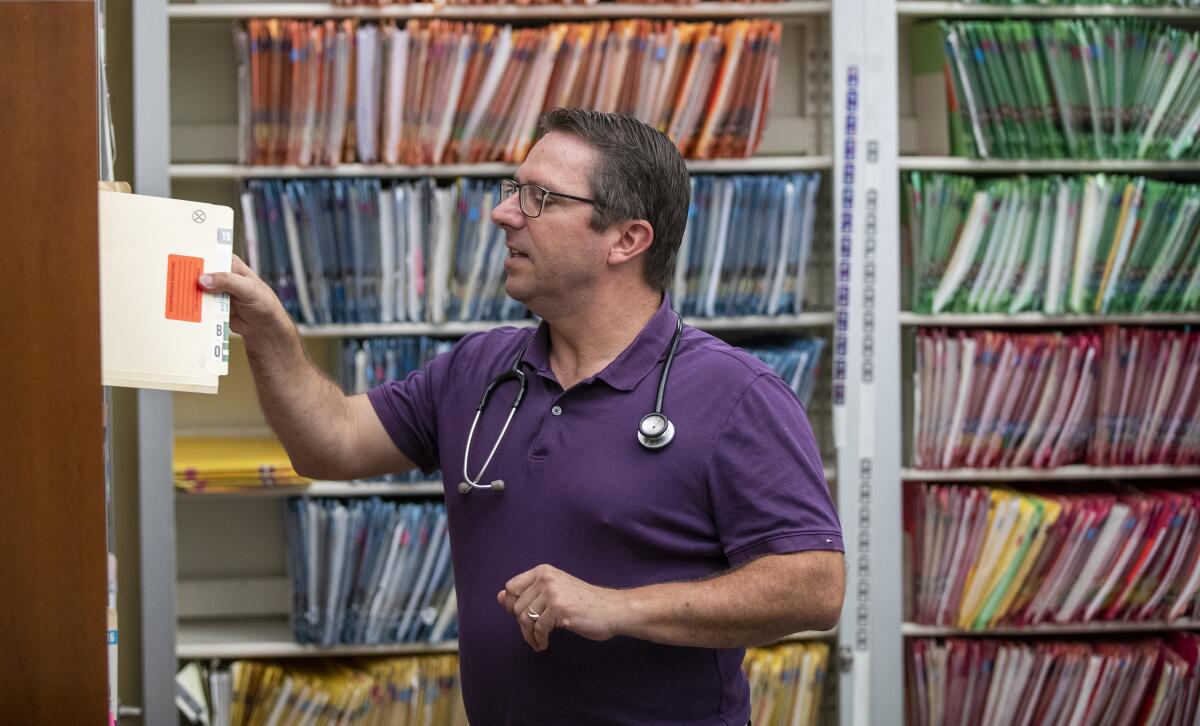

Sears’ probationary status means that he must have another doctor review his files occasionally. But he’s still able to see patients and write medical exemptions to vaccines.

“Almost all of [my] patients have already decided not to continue vaccines,” Sears said. “And they’re just relieved and happy that there’s a pediatrician that will take them. ... I’m very happy to see them because I don’t discriminate based on vaccine status.”

::

The climate in California surrounding vaccines has become particularly volatile in recent months as state lawmakers weigh controversial changes to the state’s immunization laws.

In 2015, lawmakers passed a bill that did away with vaccine exemptions based on a person’s personal or religious beliefs, prompting thousands of parents to come to the state Capitol in protest. It meant children who are not fully vaccinated can attend school or daycare only if a doctor concludes there is a medical reason to skip some or all shots.

Last school year, 4,812 kindergartners obtained medical exemptions from vaccines, a 70% increase from two years earlier, according to data from the California Department of Public Health.

Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), author of the 2015 bill, contends that parents are seeking out “unscrupulous” doctors who are willing to write medical exemptions for a profit, prompting him to introduce SB 276, which would give the state the power to review and potentially reject the orders. In crowded legislative hearings this year, Pan has repeatedly pointed to Sears as an example of a doctor who has financially benefited from writing questionable exemptions.

Sears said he has “gotten a lot of new patients” because of Pan’s vaccine law in 2015, but that his schedule has always been booked five to six weeks out because of his “open approach to vaccines.”

Pan, a pediatrician, said parents seek out Sears because he says what they want to hear.

“As a pediatrician, as a physician, you’re supposed to help parents,” Pan said. “You’re supposed to help their children by recommending what’s best for their children, not simply profit from feeding people’s anxieties and fears.”

The bill could significantly affect Sears if it is signed into law. While under investigation by the medical board, doctors would be barred from writing new medical exemptions. In addition, the medical board would be able to review medical records related to a child’s vaccine exemption. If a doctor granted vaccine exemptions for a reason now found to be illegitimate, he or she could face sanctions — including license revocation.

Sears said he’s not worried that further scrutiny will result in him losing his license, adding: “My lawyers assure me it’s probably not going to lead to that.”

The bill passed the Assembly on Tuesday and now heads to the Senate, where an earlier version passed in May. Despite initially saying he’d sign it, Gov. Gavin Newsom said Tuesday that he wants changes to the bill before it reaches his desk.

During hearings on SB 276, opponents — many of them parents toting children they say were harmed by vaccines, hung on Sears’ every word as he testified before lawmakers. When Sears interrupted lawmakers to counter what he believed were false claims by supporters of the bill, the crowds packed into the room would call out, “Let him speak!” Afterward, Sears was greeted like a celebrity on a par with another staunch vaccine critic — Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Some of the parents shook Sears’ hand and thanked him for his commitment to the cause, others excitedly pointed him out and snapped his picture. He is their doctor, even if he doesn’t treat their children.

At each step of the legislative process, as the bill was passed by committee after committee, Sears has returned to Sacramento to fight against the bill, navigating crowded Capitol corridors where he is called both an “opportunist,” and “a saint.” And it’s unlikely you’ll find middle ground between the extremes.

More to Read

Updates

6:16 p.m. Sept. 3, 2019: This article was updated to reflect that SB 276 has been passed by the Assembly.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.