Ethnic studies may soon be mandatory. Can California get it right?

Angela Warren always assumed her father, a native of El Salvador, entered the United States via airliner. It took an assignment in her high school ethnic studies class to learn that he crossed the border alone at 14, terrified of being caught. When he reached the American side, he fell to his knees and gave thanks.

That eye-opening view of her family’s past inspired Warren’s mission to change the present. At a time when watching the news can make her feel anxious and helpless, Warren, now an 18-year-old college student, said it’s the lessons of her ethnic studies class that generate intellectual awakening and empowerment.

“It made me feel comfortable with myself knowing my family history and knowing the history of our people,” said Warren, who attends Marymount California University.

In actions that would affect more than 6.5 million California students, state lawmakers are poised to make ethnic studies a graduation requirement in high school and at Cal State universities, raising the stakes for a team of educators drafting the model curriculum, those who are arguing for changes to it, and also for critics — who see an academic field dominated by one-sided, insular political correctness and separatism.

Warren’s former teacher Ron Espiritu believes ethnic studies classes have become an educational imperative. He sees his students grapple with weighty issues — inequality, hate speech, police brutality, polarized political discourse, immigration raids and mass shootings.

Ethnic studies has its own academic language from hxstory to cisheteropatriarchy.

“How do we not talk about those issues on Day 1 with our students?” the Camino Nuevo Charter Academy teacher asked.

The high school requirement — the first such in the nation, according to a legislative analysis — appears to have broad backing among Sacramento lawmakers and beyond. A separate bill, mandating an ethnic studies class for every Cal State student, has drawn a mixed reaction at campuses. Although there is wide support for ethnic studies courses, some Cal State faculty and administrators strongly oppose a state requirement. The public’s chance to comment on the model curriculum closes Thursday.

“California is committed to getting this work right,” Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the state Board of Education, said in a letter to the Los Angeles Times. “We will not accept a curriculum that fails to address difficult issues in a way that promotes open-mindedness and independent thought — skills our students need to understand vital societal and civic forces.”

At its core, supporters say, ethnic studies classes teach students how to think critically about the world around them, “tell their own stories,” develop “a deep appreciation for cultural diversity and inclusion” and engage “socially and politically” to eradicate bigotry, hate and racism. This description, from the draft of the model curriculum, is meant to guide California K-12 educators in creating coursework whether or not the new graduation requirement becomes law.

Among those who say the proposed curriculum falls short of its lofty goals is Williamson M. Evers, a research fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution, based at Stanford.

“Instead of an objective account of the history of ethnic groups and their current situation, this is a biased portrait emphasizing suffering and victimization, serving as a kind of road map to create ideological activists based on racial identity,” Evers said. “Will you be graded on having the politically correct answers?”

Among other things, Evers objects to the association of capitalism with forms of oppression. He also is put off by the academic language that has grown up around the field, which employs such terms as “herstory” and “hxrstory” to replace “history.”

The draft curriculum also has drawn criticism from some Jewish and pro-Israel groups for its treatment of Arab-Israeli issues and its omission of anti-Semitism.

Supporters of ethnic studies embrace their intensely political focus. The model curriculum dives right into how the Trump administration has handled unaccompanied immigrant children: “Rather than reunifying children with family members, family members are being detained and possibly deported for immigration violations. Furthermore, the administration is trying to roll back existing legal protections for the length of stay and quality of treatment at immigration detention centers.”

“We are teaching an antiracist curriculum,” Espiritu said. “We are trying to teach students what is oppression, what are systems of oppression, how do they interact with minorities.”

In California, as nationwide, these courses are increasing in number, with grade-school enrollment nearly doubling from 8,678 in 2013-14 to 17,354 in 2016-17, according to the state Department of Education. In 2014, 19 schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District offered ethnic studies. Last year the number was 83, officials said.

How students engage

The assignment that energized Warren called for her to interview family members, trace their languages, make a timeline of their history and draw a map of where they came from. Warren had never fully considered her father’s struggles. Inspired, Warren joined a Chicano/black studies group at a local YMCA, through which she volunteered to feed homeless people and to work with elementary school students.

For white and middle-class students in Santa Monica, ethnic studies class has been an exercise in empathy. One project came about after students realized Advanced Placement classes were filled mostly with white students from affluent backgrounds — so they set out to develop a plan to address this inequity.

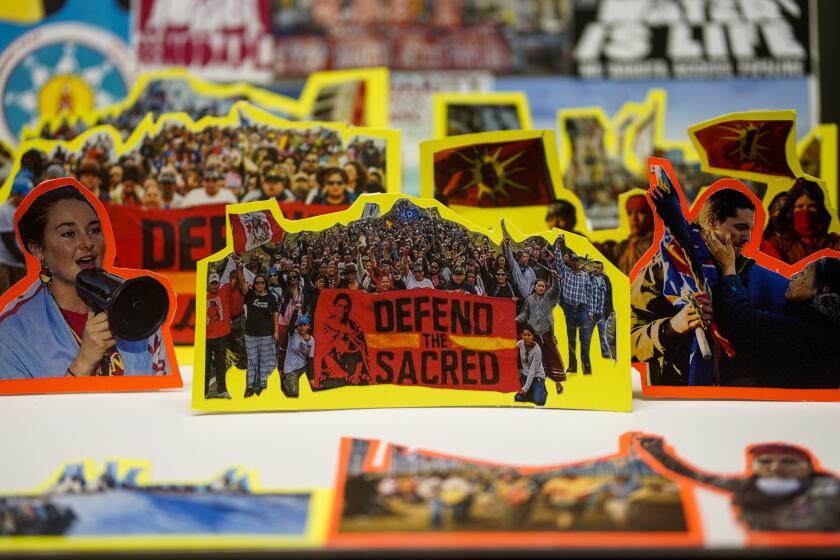

Ethnic studies are rooted in California activism — in 1968 when the Black Student Union and a coalition of student groups at San Francisco State University, known as the Third World Liberation Front, began a student strike calling for ethnic studies. Scholars see their field as an antidote to mainstream doctrine.

“K-12 education is based around the Eurocentric narrative,” said R. Tolteka Cuauhtin, a Los Angeles teacher who co-chaired the advisory committee that created the draft curriculum. “This one class offers the other side.”

The proposed curriculum focuses mainly on four groups: Latinos; Asian Americans; African Americans; and indigenous peoples, those who lived in the Americas before the arrival of colonizers from Europe. Ethnic studies curriculum has traditionally been framed around the experience of these four groups in the U.S. In addition, there’s material on Arab Americans, Pacific Islanders, and on Central Americans, distinct from Mexican immigrants. These three groups were included at the request of these communities.

Pro-Israel groups object

The evolving curriculum was not on the radar of Jewish groups during its conception. Supporters of Israel are troubled by about a dozen pages in the 578-page guide, as well as by its glossary.

In capturing the sweep of the Arab American experience, for example, the materials describe immigrants from Palestine who arrived in the U.S. after the “Nakba.” The word means “catastrophe” in Arabic, and it’s how many Arabs refer to the creation of Israel and the flight of Arabs from Israeli territory. The use of that term, especially without caveats, raised alarms among pro-Israel groups.

Moreover, the glossary for the curriculum includes “Islamophobia” but not “anti-Semitism.”

Critics also object to what they see as an overly positive definition of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement, known as BDS, which advocates for exerting economic pressure on Israel to come to terms with Palestinians. Sample topics for coursework include the “Call to Boycott, Divest and Sanction Israel” and “Comparative Border Studies: Palestine and Mexico.”

The Legislature’s 16-member Jewish caucus, which includes non-Jews, expressed strong reservations. Those who signed the letter included Assemblyman Jose Medina (D-Riverside), who wrote the bill with the high school graduation requirement.

“Despite the significant contributions of Jews to California’s history, politics, culture and government — and our community’s longstanding struggle against hatred and discrimination — the [curriculum] effectively erases the American Jewish experience,” the caucus wrote in a July 29 letter to the state’s Instructional Quality Commission, which will soon be conducting its own review.

Caucus members stressed that they did not oppose ethnic studies. “It would be a cruel irony if a curriculum meant to help alleviate prejudice and bigotry were to instead marginalize Jewish students and fuel hatred and discrimination against the Jewish community,” their letter states.

Although the official public comment period ends this week, state officials say ample opportunity remains to revise the curriculum. The state Board of Education is scheduled to approve a final version by March of next year.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.