A cliff collapse. Three deaths. More bluff failures expected with rising seas

When we go hiking in California’s rugged mountains, we know to look out for bears and lions.

When we set off into the vast, bone-dry high desert of Joshua Tree, who doesn’t bring extra water?

When we stand too close to the edge of a coastal bluff, everyone yells to step back.

But resting under the shade of these cliffs in view of the ocean, it’s easy to forget what could come crashing down from above.

People often think about the beach as a place to swim, to read, to relax. In reality, it’s the tip of a wild, dynamic system that is constantly moving and succumbing to the forces of nature. These sweeping cliffs that make California’s coast so iconic were themselves formed by tectonic shifts and landslides over the centuries. And from the rubble of every collapse, more sand is made for beaches.

Last week , on a popular surf beach north of San Diego, tons upon tons of sandstone crashed down on Anne Clave, her mother, Julie Davis, and aunt Elizabeth Charles. A beautiful beach day — meant to celebrate Charles beating cancer — in seconds turned into a frantic, fatal scene of beach chairs strewn aside, cadaver dogs, teenage lifeguards digging people out from the crush of heavy rocks. From the water, swimmers looked on in horror.

Cliff collapses are one of California’s many hidden dangers. Like earthquakes, we know what areas they’ll most likely happen — but nailing down when, and how big, is not an exact science.

Compounding all of this is the rising sea, as waves hammer away at the vanishing coastline with every tide and storm. The sea is rising higher and faster in California — a reality more officials are now confronting. Just last week, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill that amended the state’s Coastal Act to say that sea level rise is no longer a question but a fact.

“With sea level rise, there’s no doubt that we’ll see more cliff failures along the coast,” said Patrick Barnard, research director of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Climate Impacts and Coastal Processes Team. “Cliffs erode, that’s what they do … and we certainly expect more events like this the more the bottom of those cliffs are being hammered away by the ocean.”

Cliffs are particularly difficult to study because they tend to erode slowly over time, punctuated with sudden collapse — often without warning — from landslides or during a storm. The strength of the rock, cliff height, sediment composition, wave action, the slope of the beach and the slope of the seafloor all factor into their stability.

How rainfall and groundwater seep in can also build up pressure and lead to cracks and collapses. The human urge to develop right to the edge — building blufftop homes, landscaping, carving out coastal roads — further affects erosion by adding weight to clifftops and altering water drainage.

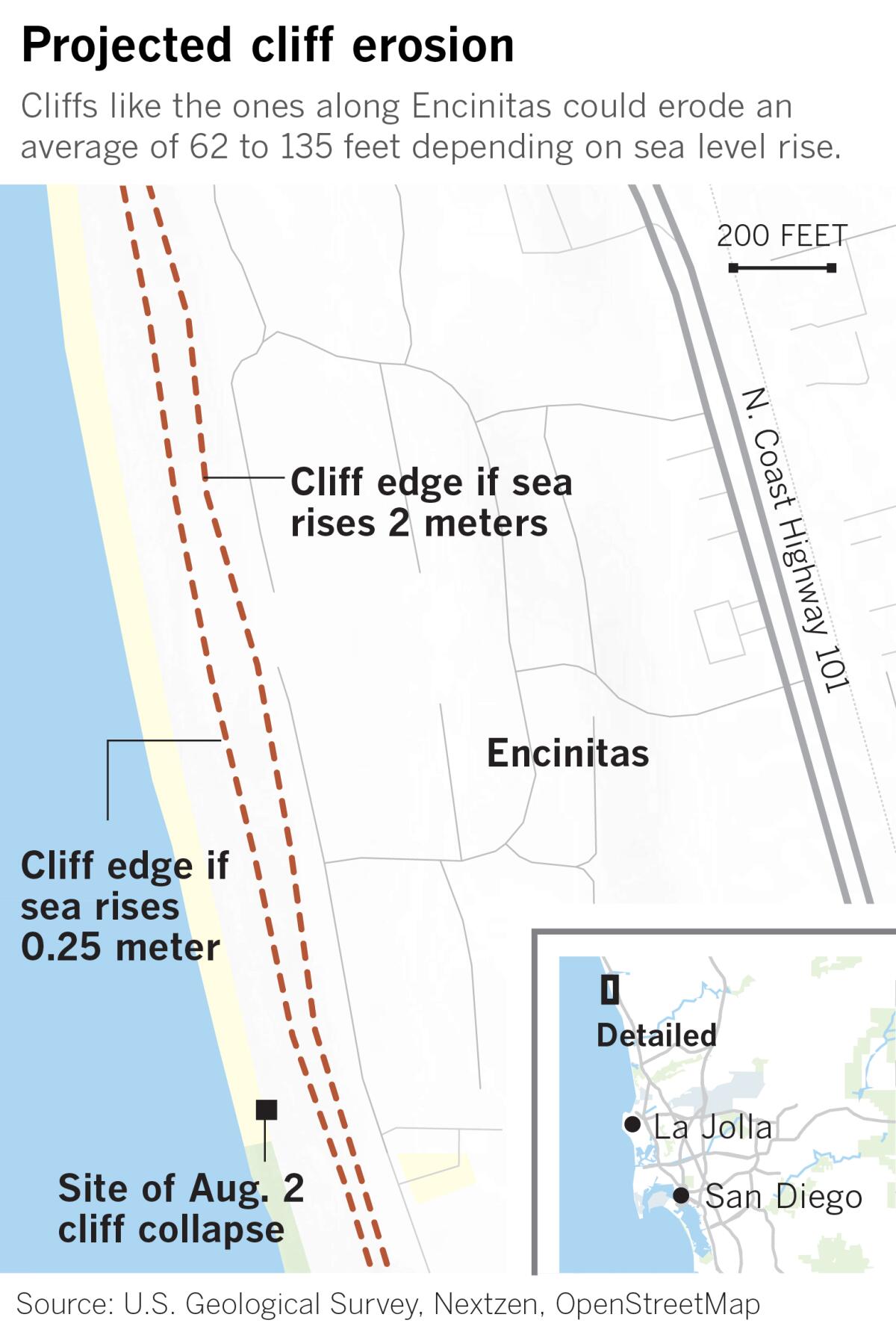

Altogether, cliffs in Southern California alone could erode more than 130 feet by the end of the century if the sea keeps rising, Barnard and a team of scientists found in a recent study.

The science is there on cliff retreat over a long expanse of time, he said, but much more work could be done on a more decade-by-decade, perhaps even season-by-season basis.

“We know that California cliffs on average erode about a foot a year, but that’s a long-term average,” he said. “In many cases, they won’t do anything for 30 years, but then there’s a 30-foot failure.”

Scientists often think in these averages, he added, which can be a challenge when talking about cliff erosion and other climate change issues to the public. Stretched over a long period of time, an average — however extreme the changes may be — might not sound like much. But just two or three large collapses could encompass basically the entire expected erosion of a cliff in one century.

Adam Young, a project scientist at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography who has spent years studying and building a comprehensive database of cliff erosion in California, hopes that patterns and lessons from historic collapses could help the state better plan for the future.

His studies so far have identified areas such as Big Sur, San Onofre State Beach and Daly City with cliffs that had particularly high rates of erosion. He also found that cliffs with high erosion rates in recent decades were often preceded by periods of very little erosion.

The cliff collapse in Encinitas that killed three people underscores the dangers of bluff erosion along the California coast.

Young has been busy in recent months with numerous cliff collapses in northern San Diego County. Sections of the cliffs in Del Mar collapsed three times in just a few weeks last fall, threatening the coastal railroad. A large landslide at Torrey Pines last month crashed down early enough in the morning that no beachgoers were hurt.

“It’s definitely been more active than it has been in the last few years,” he said. “We’re still trying to understand what happened.”

Attention is now laser-focused on Grandview Surf Beach in Encinitas, the site of last week’s collapse. The bottom part of the cliff — the part that fell — is a compressed, compacted sand and claystone material that’s millions of years old. One cubic yard, about the size of a washer machine, weighs thousands of pounds. This dense material is what creates the cliff’s steep, almost vertical face.

On top of this layer is essentially ancient beach — what scientists call “marine terrace” — that lifted 30, 40, 50 feet up after earthquakes and other seismic activity. This old sand is somewhat cemented into a soft rock that can more easily erode and fall back onto the beach below.

These cliffs have long been active. In 1938, the Self-Realization Fellowship built the Golden Lotus Temple just 10 or so feet from the bluff edge. Less than five years later, the temple collapsed when the bluff caved to large waves and heavy rainfall, according to a study titled Lost Neighborhoods of the California Coast by longtime coastal scientist Gary Griggs. The temple was dismantled and hauled away — a plaque today at the top of the bluff marks the original location.

By the 1980s, maps by the state geologist had identified the entire Encinitas shoreline as susceptible to landslides. The stairway to the beach itself collapsed because of a bluff failure during the 1982-1983 El Niño winter. It took almost 10 years for officials to agree on how to rebuild in a way that was safe and stable. The city’s beach safety guide today includes a large section on cliff collapses.

Oceanfront property owners often react to these threats by armoring the coast with seawalls — about 30% of Southern California’s shoreline today is behind some form of hard protection. But these structures prevent the cliffs from eroding and providing the natural supply of sand to beaches.

Beaches continue to shrink as more and more seawalls prevent this natural creation of sand — not to mention how the damming of rivers and creeks has prevented fresh sand from making it to the coast. About 10% to 20% of the sand on beaches in Southern California today comes from cliff erosion.

Seawalls also fix the cliff in place, drowning out the beach in front as the sea rises. If this coastal squeeze continues, two-thirds of beaches could vanish by the end of the century.

The blufftop homes near last week’s collapse were spared and not in immediate danger, but a likely outcry from this tragedy will be a call for more seawalls. The California Coastal Commission, the state agency in charge of regulating the coastline, has fought owners in the past over seawalls and building too close to the edge. A precautionary 40-foot setback is the rule in Encinitas, unless a site specific study shows otherwise.

“When people come to us applying for a seawall, they will regularly include the public altruistic benefit that it will make the beach less risky from collapses like this,” said Lesley Ewing, the commission’s senior coastal engineer. “While in the short term that may be the case, for the longer term, there will be no beach at all.”

And the less beach there is, the more people end up sitting closer to the bluff.

“Our beaches are narrowing. There’s not a whole lot of places for people to sit outside the danger zone,” said Brian Ketterer, who oversees beach operations for California State Parks. “The bluff is enticing, I get it. You’re at a hot, sunny beach. There’s not a lot of wind. Being in the shade of the bluff can be 8 to 10 degrees cooler.”

Encinitas beach cliff collapse area in Southern California where three women died is ‘still active,’ so a nearby lifeguard tower has been moved.

Placing caution signs on the bluff itself is tricky, he said, because bolting anything in might affect stability. Warnings at the base of the beach is unrealistic: For many beaches in the area, the water comes right up to the cliffs during high tide and would wash any signage away.

The lifeguard tower at Grandview gets flooded so often that it is set on skids. City officials each week have to straighten out the structure, which sinks and becomes unlevel with each tide.

Lifeguards are proactive about spotting bluffs that might be cracking and cautioning people from getting too close. Engineers come by, studies are conducted. But for park officials, the biggest challenge might be that deceiving sense of safety most people are lulled into whenever they drive past multimillion-dollar homes and landscaped roads, park their car at a vista, and experience what feels more like an urban outing than a day in the wild.

Ketterer has seen many ups and downs in his 35 years on the job, but last week’s deaths still haunt him. The collapse was just 40 feet from an open beach tower, not too far from the stairs. Young lifeguards rushed alongside paramedics in frantic triage mode.

Numerous people looked on in shock, remembering the many times they themselves sat there for shade. Geologists pointed to a fissure that was worrisome and declared the site still active. More signs went up, rescue crews cleared the scene, a few fire officials and lifeguards kept guard overnight.

Like clockwork, the tide rolled back in. The mighty Pacific, its turn at last, carried everything out to sea.

By morning, Ketterer said, only one rock was left. It was like yesterday had never happened.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.