You might — still — have pandemic parental burnout

This is the Nov. 15, 2021, edition of the 8 to 3 newsletter about school, kids and parenting. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox every Monday.

For a moment, I’d like you to remember (or imagine) life as a parent in 2020.

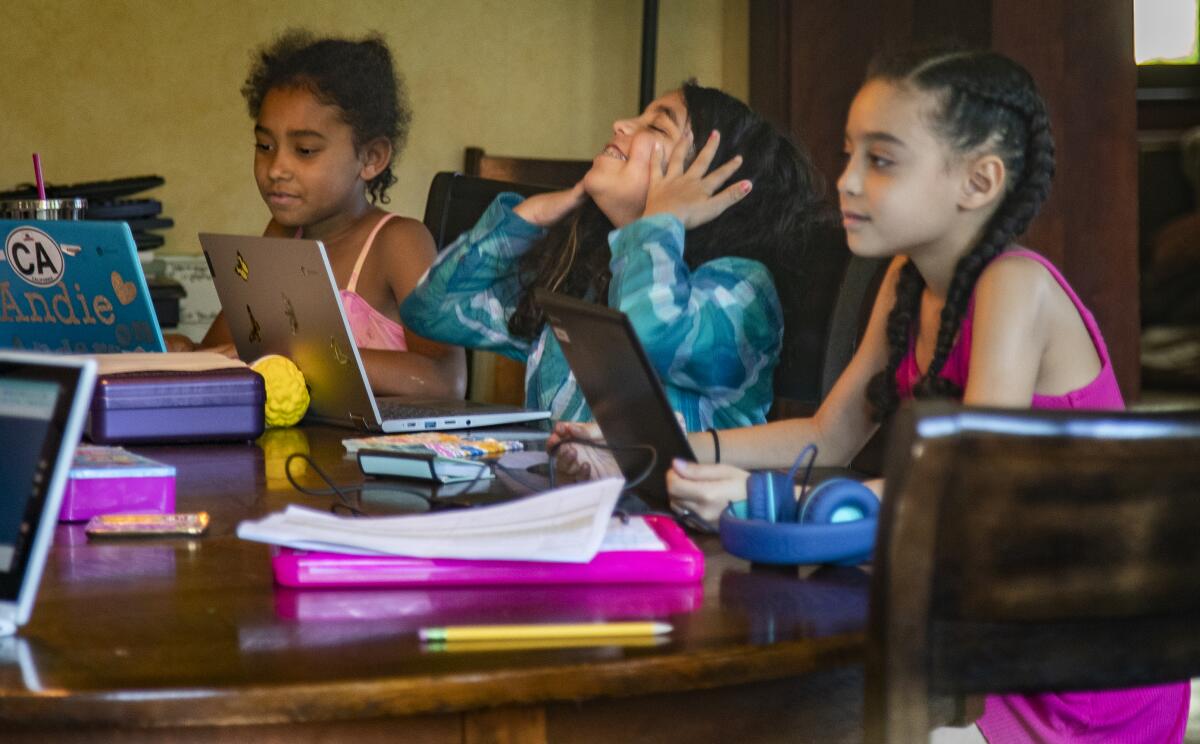

You’re home with your kids 24/7. They need help with homework, logging onto Zoom class. Your boss wants 20 million things from you and so does the 5-year-old who is throwing a tantrum at your feet. Your kids look up to you as a model for what to do in times like these, but you have never lived through a pandemic, so you are just as confused and afraid as they are. You just can’t show it.

You feel like you are falling short. You are absolutely fried. And there is no escape.

Thank God we’re not in that place anymore! Kids are back at school and you can hang out with people outside of your household and things are generally a whole lot less apocalyptic. Yet you’re still feeling … not great.

You may be burned out. Yes, still.

According to researchers from Stanford University and Belgium’s Catholic University of Louvain, parental burnout is a state of “intense exhaustion related to one’s parental role, in which one becomes emotionally detached from one’s children and doubtful of one’s capacity to be a good parent.” In short, it’s the body‘s and mind’s response to the chronic, overwhelming stress of being a parent.

Like job burnout, parental burnout can cause depressive symptoms, addictive behaviors, poor sleep and increased conflict with others. But unlike job burnout, you cannot resign from your parenting role or go on sick leave. Even fantasizing about no longer being a parent is taboo.

“It’s the burnout we can’t talk about, which can be very isolating,” said Robyn Koslowitz, a clinical psychologist and director of the Center for Psychological Growth in New Jersey.

Koslowitz coaches parents with traumatic upbringings on how to give their little ones a healthy childhood when theirs was anything but (she calls it post-traumatic parenting).

“When the pandemic hit, suddenly everyone was experiencing what post-traumatic parents experienced all the time,” Koslowitz said. “When you’ve experienced trauma, the world is unpredictable. You’re always adrenalized, waiting for the next shoe to drop.”

The demands of everyday parenting were compounded by the claustrophobic, frightening circumstances of the pandemic. In the first stage of burnout, you were likely overcome with exhaustion. Then you may have distanced yourself from your children to preserve your limited energy (known as the detachment stage).

“Some parents I work with just come home, take a shower and go to bed,” said Keisha Henry, a psychotherapist based in South Florida. “They’re not connecting, not asking about homework.”

So why are many parents still burned out even though many of the pandemic’s stressors have lifted?

For one, kids are still dealing with the effects of the past 20 months. They’re grappling with unprecedented levels of anxiety and depression, re-establishing friendships and catching up academically, said Reena Patel, a San Diego-based psychologist and parenting expert. Empathetic parents are bound to internalize those struggles.

“There’s that saying: ‘You’re only as happy as your saddest child,’” Patel told me.

And few have had the luxury of time to process what happened during the pandemic, Koslowitz explained. The exhaustion and guilt of not being fully present for your kids may still be there, corroding your quality of life and ability to connect with your children.

“One of the things we do in the trauma world is process and re-process. We debrief right after the event, and then we wait a while and re-process. Most parents don’t know how to do that,” Koslowitz said. “ We went from the pandemic, back to normal life in an instant. There wasn’t a pausing period to acknowledge, ‘That was tough, let me take a breath. Let me not try to immediately catch up on all the dentist appointments and clothes shopping for the kids I missed this year.’”

In other words, Koslowitz said: “We’re building on a foundation of shifting sand.”

Unsurprisingly, certain conditions make parents more vulnerable to burnout. Financial insecurity, lack of support, and social isolation are all risk factors that have become much, much more common during the pandemic.

A 2021 study by Belgian researchers Isabelle Roskam and Moïra Mikolajczak found that parents from more individualistic (typically Western) countries — which tend to value perfectionism and discourage parents from asking for help — had higher rates of parental burnout than those from Eastern countries.

Single parents, parents of kids with special needs, and parents who’ve experienced systemic oppression are particularly susceptible. For example, many parents of color have the added stress of being unsure of whether they or their loved ones would be provided adequate treatment if admitted to a hospital with COVID-19, Henry said.

How do you get out of such a rut? First off, acknowledge that you are burned out and you’re not feeling great about your relationship with your child, Patel advised. Communicate with your family that you need some space and time for yourself, if possible.

Restoring your sense of self and well-being is paramount. “Self-care is child care,” Koslowitz said. Your kids will be much better off if you feel like a whole, regulated human being.

“Any mental load you can take off your plate gives you more mental energy to attune to your kid,” Koslowitz said. “Mental load is the grit that burns an engine out.” For example, you could spend a morning meal-prepping for the entire week so you don’t need to think about what’s for dinner Wednesday night.

You should also be intentional about reconnecting with your kids. Start by asking them how their day has been and what they need; make that a ritual, Henry said.

Share joyful moments with your kids, too. Do something you’ll both enjoy: take a walk, bake, do a puzzle together. Koslowitz finds that reading storybooks to younger children is a way to connect when you don’t have the headspace for much else.

Finally, seek support from a mental health professional if the problem persists.

“A burned-out brain cannot attune,” Koslowitz said. “Attunement is the building block of attachment, and you must be able to do that to give your kid a happy, healthy childhood.”

Enjoying this newsletter?

Consider forwarding it to a friend, and support our journalism by becoming a subscriber.

Did you get this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every week.

Mental health, critical race theory and other matters of note

What do high school students want? Less stress. Access to technology. The keys to academic success. My colleague Howard Blume describes the results of a poll of Los Angeles Unified School District students this way: “Students in Los Angeles public schools said they have suffered due to the COVID-19 pandemic and expressed a ‘non-negotiable’ need for academic success: mental wellness.”

Along those lines, San Diego Unified had an optional “mental health day” Friday. Students could take the day off from school, and about half of them did. But, as our sibling newspaper, the San Diego Union-Tribune, reports, some parents were just ticked off.

“Critical race theory” is a hot-button issue all over the country and states are passing laws to outlaw it, even if they were never actually teaching it. California is doubling down with an ethnic studies curriculum that has some overlap with critical race theory. Times education writer Melissa Gomez looked into it.

A San Diego County judge dismissed a lawsuit challenging Gov. Gavin Newsom’s school mask rules.

What do you get when you combine midwifery with herbalism? You get dandelion essence for pregnancy, Mexican honeysuckle for childbirth and blue corn atole for nursing. A look at “Hood Herbalism.”

What else we’re reading

A new science museum has opened in Sacramento — the SMUD Museum of Science and Curiosity. (For those unfamiliar with Sacramento, SMUD is the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, the city-owned power company.) Sacramento Bee.

America has a reading problem. Even before the pandemic, reading scores were dropping. Remote learning didn’t help. The Hechinger Report.

No surprise, but a UCLA study finds that people who face discrimination as kids are more likely to have mental health problems as adults. KQED Mindshift.

Here are some tips for recharging your children, who are probably worn down by the past 20 months of pandemic. CNN.

I want to hear from you.

Have feedback? Ideas? Questions? Story tips? Email me. And keep in touch on Twitter.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.