Actors can start selling AI voice clones to game companies under this new deal

Recording new voice-overs without speaking a word: For a busy voice actor, it might sound like a dream — unless that actor is worried about artificial intelligence being used to devalue her work and make hiring her unnecessary.

But under a new deal with an artificial intelligence company, members of the Screen Actors Guild will be able to create and license digital simulations of their voices for video games and other projects while enjoying safeguards against their potential misuse, the Hollywood labor union announced Tuesday.

Touting an agreement with Replica Studios — a tech firm that says it is “building the world’s greatest library of AI-powered voice actors” — during an event at the CES tech expo in Las Vegas, SAG-AFTRA National Executive Director Duncan Crabtree-Ireland described the deal as an example for how other tech companies can build trust with showbiz talent.

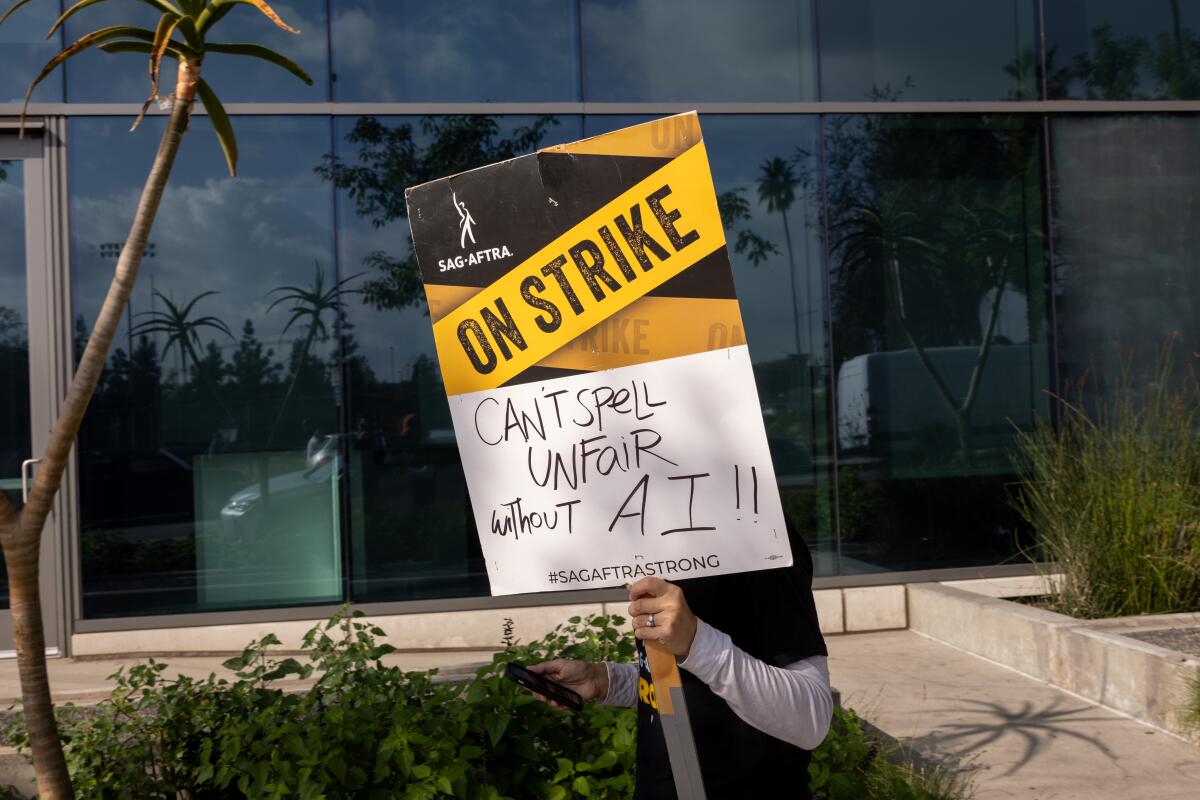

The deal comes in the wake of SAG-AFTRA’s protracted strike last year, in which the union sought expanded protections against AI from the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, or AMPTP, the group representing Hollywood’s major producers. The contract that the Guild ultimately secured mandated that the studios get permission from actors in order to digitally clone them, and pay for the use of those clones.

SAG-AFTRA members will vote this month on whether to authorize union leaders to call a strike against video game companies. Here’s how we got to this point.

“Like our recently negotiated AMPTP … terms, the Replica agreements are an expression of SAG-AFTRA’s intent and ability to work with employers to create terms that benefit and protect our members, and allow them to engage with opportunities driven by new technologies,” Crabtree-Ireland said from a lectern during the CES event.

The Replica deal will allow professional voice-over artists to “safely explore new employment opportunities for their digital voice replicas with industry-leading protections tailored to AI technology,” according to SAG-AFTRA. Simulated voices licensed under the deal can be used in video games and “other interactive media projects,” the union added.

The agreement establishes minimum rates for voice actors, Crabtree-Ireland said, and includes guardrails to ensure that performers know what projects a digital voice replica will be used in and that they consent to its use in future projects. Their data must also be stored safely.

“This is a great example of AI being done right,” said SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher in a statement.

Protections for game voice actors fall under a SAG-AFTRA contract for interactive work. But that contract, negotiated in 2017, did not include protections around AI.

Voice actors have said they know society can’t stop AI technology from advancing. Instead, they hope that workers can secure contracts that would require their consent to reproduce their voice or likeness and compensate them when that happens.

An Assembly bill would give actors and artists a way to nullify provisions that allow studios to digitally clone their voices, faces and bodies with AI.

SAG-AFTRA has been negotiating its video game contract, the Interactive Media Agreement representing about 2,500 performers, for more than a year. In September, members voted to authorize union leaders to call a strike against video game companies.

Although the technology to reuse a likeness or modify a voice has existed for years, actors say AI ups the ante because it can scrape more information more efficiently and potentially turn it into a plausible clone of an actor, combine actors’ work or pass as a new, ersatz artist.

“We’re creating new revenue streams here; we’re not replacing the old way of doing things,” said Shreyas Nivas, chief executive of Replica Studios. Explaining what this deal might look like in practice, he said that the popular video game “Red Dead Redemption 2” included 500,000 lines of recorded dialogue, and suggested that automated voice acting could make that process cheaper and more efficient.

Game voice actors say AI poses an equal or even greater threat to performers in the video game industry than it does in film and TV — particularly because many work in voice-over.

“The capacity to cheaply and easily create convincing digital replicas of performer voices is already here and widely available,” SAG-AFTRA said in a message posted on its website. “You can find the tools to do it yourself with a simple Google search. Without protections, not only will this be the future of how voices are recorded for video game characters, but your own voice recordings will be used to train the AI systems that replace you.”

Voice actors have pointed to game “mods” — in which players or fans of a game alter content — as proof that their likenesses could be used without their consent and in ways that they would not approve. Last year, actors decried mods in the popular role-playing game Skyrim, which used AI-generated voices based on actors’ performances and cloned them for pornographic purposes.

Conversations between Replica and SAG-AFTRA began several years ago, Nivas said.

The SAG-AFTRA strike, as well as the accompanying Writers Guild strike, found stakeholders across Hollywood raising concerns about the role artificial intelligence will play in their industry. Even after SAG leaders secured a contract, some union members maintained that its language left studios too much latitude to use AI going forward.

Crabtree-Ireland nodded to those critics during the CES event, stating that “AI technology is not something we can block” and instead arguing that the union’s goal should be to “channel and direct that AI technology in a way that supports human creativity” in collaboration with amenable companies.