Tech giants enlist mom and pop shops as antitrust allies

Online platforms made Mimi Striplin’s dream of selling handmade jewelry possible. Initially selling her earrings and purses on Etsy Inc., Striplin built enough of a customer base to quit her day job, market her wares on Facebook and eventually open a shop on Spring Street in Charleston, S.C., where new customers and devoted fans find her on Google Maps.

This year she spoke with the offices of her South Carolina senators to warn that antitrust bills introduced in Congress risked complicating the online tools she uses not just to reach customers, but also to organize her team, inventory and shipping.

Her argument wasn’t just on her own behalf. She was part of an accelerating campaign by giant technology platforms to use small-business owners to lobby against a series of antitrust bills aimed at Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Amazon.com Inc., Facebook and Apple Inc.

To build a chorus of popular opposition to this legislation, Google posted alarming alerts to the millions of marketers and business owners who use the company’s tool for buying ads and promoting themselves in search. A message at the top of Google’s online dashboards now warns these customers that “proposed legislation could make it harder to find your business online.”

But large tech companies aren’t the only ones tugging on congressional heartstrings with stories from Main Street. A network of anti-monopoly and civil society groups are also using small businesses to make the exact opposite claim — that Big Tech preys on the little guys and makes it impossible for them to operate without relying on internet monopolies.

“Their argument is basically explaining why they need to be broken up and regulated,” according to Stacy Mitchell, co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “These companies have cornered the online market, they’ve become gatekeepers, and they’ve used that power to take small businesses hostage.”

The competing pitches featuring small-business owners have played out over the last year in virtual roundtables and Zoom calls with congressional staff, according to tech lobbyists and antitrust advocates. Tech giants and their industry groups are asking lawmakers to take more time to study the unintended consequences of bills that would force covered platforms to change how they present products to consumers and interact with competitors.

But there is a tight legislative window in the first half of next year to pass these measures before many lawmakers turn their attention to November’s midterm election. Even though the bills targeting Big Tech have bipartisan support, Republicans winning one or both chambers of Congress could scramble the antitrust agenda.

The four antitrust bills targeting Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple cleared the House Judiciary Committee in June on bipartisan votes, but they still need a vote in the full House. Two of those measures have companion bills in the Senate.

Rob Retzlaff, head of the Connected Commerce Council, a Google- and Amazon-funded group representing 15,000 small companies, said his members have voiced “frustration that they’re not being heard” by lawmakers.

“Congress seems to be out of touch with the current reality,” Retzlaff said. “The focus Congress should be having is working with small businesses to help them recover from the pandemic, but these bills are creating more uncertainty when their main concern is staying in business.”

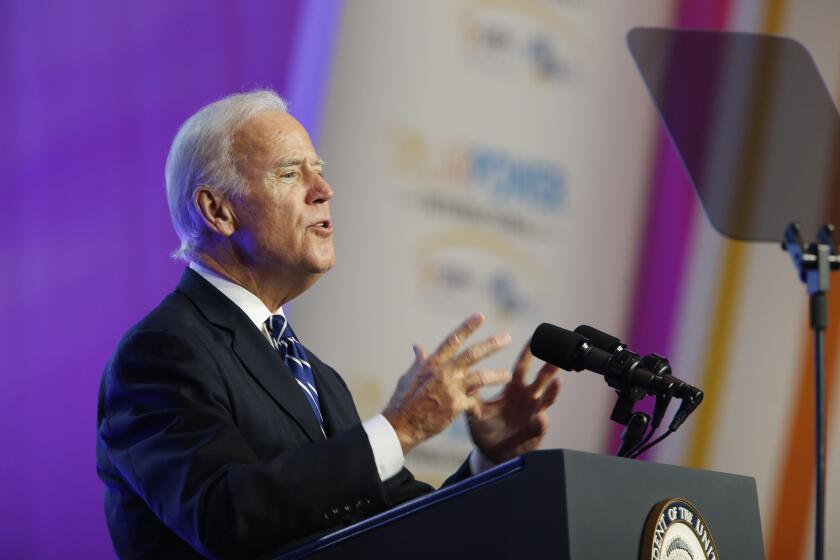

A Biden presidency could have major ramifications on U.S. tech policy.

Google has warned that one bill prohibiting companies from favoring their own products would change the way local businesses appear in search, make ads less effective and make other Google tools more clunky by forcing the company to de-integrate its products.

Mark Isakowitz, Google’s vice president of government affairs and public policy, said Congress should “carefully consider the unintended consequences for Americans and small businesses of breaking a range of popular products that people use every day.”

Congressional aides say this description of the impact of the legislation is misleading and these warnings are part of scare tactics from the tech companies.

The small-business owners touted by anti-monopoly groups emphasize the urgency of passing this legislation before online gatekeepers further consolidate their hold over the post-pandemic economy. They argue that putting limits on the likes of Google, Amazon and Facebook, whose corporate name is now Meta Platforms Inc., would allow for alternatives that could offer better ways to reach customers.

Some Google clients who received the alerts about proposed legislation chafed at Google’s tactics. Mike Blumenthal, a web search consultant, called the messaging “brazen, deceptive and totally misguided.” A blog post of his that ricocheted around SEO specialists and web marketers described the move as “bamboozling small businesses to support Google in their fight to remain a monopoly.”

For an office supply provider based in Virginia, Amazon is the enemy. David Guernsey said he’s been selling paper clips, desk chairs and janitorial supplies to businesses for 50 years, counting on established relationships to resist pressure to join the legions of small firms using Amazon to reach consumers. But he says he’s worried about building new customer contacts as Amazon ramps up outreach to the school districts and companies that make up much of his sales.

“Pretty soon they’re going to own everything, I suppose, and I guess that’s their stated intention, is to sell everything to everyone,” Guernsey, who participated in a small-business roundtable last month with Senate antitrust subcommittee Chair Amy Klobuchar, said of Amazon. “The omnipresence of that organization is like nothing I’ve ever seen.”

Aaron Seyedian, who started his Well Paid Maids cleaning service in 2017, said advertising on Google and Facebook was a “totally opaque” process with a confusing, impersonal interface. He has joined advocates in favor of the antitrust legislation because he said small-business owners often feel like they have no other choice but to rely on a handful of tech companies to survive in today’s market.

Still, even though Seyedian said he pulled his ad dollars from Facebook and Google, he does pay Google to use professional Gmail for his employees — and he wouldn’t be surprised if his cleaners use Google Maps to find clients.

Seyedian’s experience echoes that of other small-business owners who say their experience with the technology giants is mixed.

The October day that Striplin, the Charleston jewelry maker, was singing Big Tech’s praises to her senators’ staff was the day after Meta’s platforms experienced global outages. She said going one day without Facebook and Instagram reinforced her instinct to diversify away from the platforms that helped get her company off the ground — focusing instead on reaching customers via email lists, her own website and drawing people into her physical store.

“Every small business who uses social media as a platform, your biggest fear is that you’re going to wake up and it’s going to be gone the next day,” Striplin said. “We work really hard as a team to make sure that we can capture those customers on our own platforms and not solely rely on Facebook and Instagram and these other tech companies that own quite a few of the things.”