What Biden’s executive order on noncompete agreements means for tech workers

The rest of the country might finally be catching up to California when it comes to workers’ right to hop between jobs.

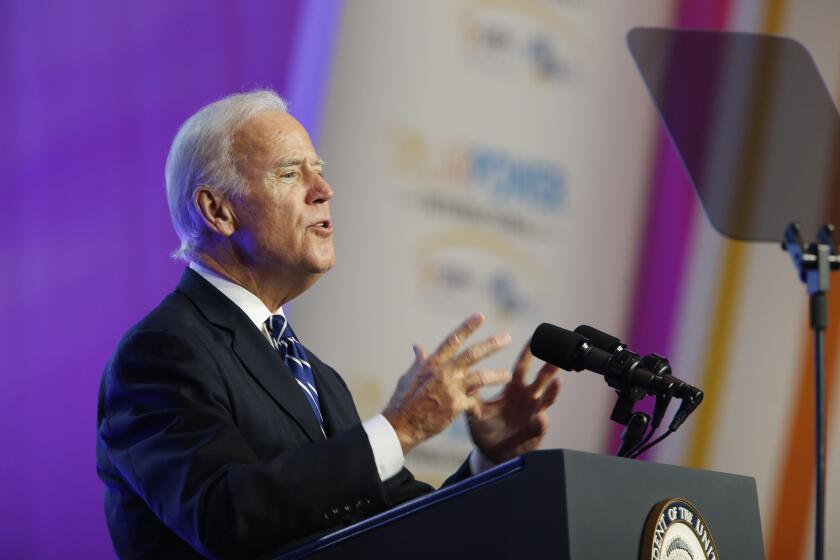

The Biden administration asked the Federal Trade Commission to ban or limit noncompete agreements nationwide as part of a broad executive order Friday. These agreements, which typically prevent workers from quitting their jobs and going to work for a competitor of their current employer, are already unenforceable in California. The administration argues that they serve to keep wages down and disempower employees from demanding better working conditions.

This executive order comes as noncompetes are on the rise across the country, with anywhere between 27% and 46% of all private-sector workers subject to the agreements, according to a 2019 survey by the Economic Policy Institute. Though broadly intended to discourage employees from taking trade secrets along with them when they switch jobs, noncompete clauses are increasingly worked into jobs across the economic scale.

The sandwich chain Jimmy John’s became a poster child for the practice in 2016, when attorneys general in New York and Illinois sued the company for barring employees from taking another job with competing sandwich shops for two years after quitting and from working for any establishment that made more than 10% of its revenue from sandwiches located within two miles of a Jimmy John’s location.

The Biden administration’s messaging around the noncompete measures has focused on what the change would mean for blue-collar workers in particular, and Friday’s action marks the culmination of at least one campaign promise. “We should get rid of non-compete clauses,” the then-candidate tweeted in December 2019.

Orly Lobel, a professor at the University of San Diego School of Law who has studied the effects of noncompete clauses for years, said that this shift in policy is “very significant” for the U.S. labor market. Based on California’s record on attracting top talent, “we have all the evidence empirically that this comparative advantage contributes not only to higher wages and worker mobility, but also a win-win for firms,” Lobel said.

“When there’s more competition, there’s more of an incentive to innovate, better fit between talent and jobs, and people don’t stagnate in the same position,” Lobel added.

Even though Biden’s order seems focused on the lower end of the wage scale, it could still make waves in the world of Big Tech, said Ryan Nunn, assistant vice president for applied research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, who has previously testified before the Federal Trade Commission about noncompete agreements.

“To the extent that we know now that noncompetes limit workers’ ability to secure outside offers and use that in wage negotiations, that applies to tech workers,” said Nunn, who cautioned that his views are his own. “And if noncompetes are limiting the ability to start new companies and to have information diffusion across firms, all of that is absolutely relevant to tech workers. ”

A presidential order designed to promote competition calls on regulators to increase scrutiny of tech companies, drug prices, shipping and more.

California’s zero-tolerance policy for noncompetes — they have been illegal in the state since 1872 — has often been credited with creating Silicon Valley itself. Scholars argue that engineers’ ability to move between firms gave the Bay Area a unique edge over the other emerging tech hubs in Massachusetts and Texas, which eventually led to its overwhelming dominance in the industry.

That hasn’t stopped employers in California from asking workers to sign noncompete agreements. A 2016 study published by the U.S. Treasury Department found that 19% of California workers had signed noncompetes, a slightly higher rate than the national average, “suggesting that firms may be relying on a lack of worker knowledge” to try to suppress job mobility.

But it has made lawsuits over breached noncompete clauses a rarity in the state, experts say. Whereas Washington-based Amazon has repeatedly sued employees for trying to jump ship to other tech firms, the company’s California competitors do so only rarely, such as in cases that allege that an ex-employee stole trade secrets on their way out the door.

The Biden administration’s efforts could level that playing field between states, and do so at a time when workforces are spreading out across the country as remote work becomes the norm, and some tech firms (though not as many as you might think) are relocating to states such as Texas and Colorado in search of greener corporate pastures.

A Biden presidency could have major ramifications on U.S. tech policy.

“When a state enforces noncompetes, it’s completely shooting [itself] in the foot when the workers are mobile,” said Lee Fleming, a professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business who has studied how noncompetes affect innovation and inventor mobility changes local economies.

He sees the shift as the right direction for workers and companies, even if it means that California is going to lose its edge. “When you make managers compete for labor and for the smartest talent, the best firms are going to win, and that’s what you want,” Fleming said.

Friday’s executive order moves the ball forward from where the Obama administration left off. In October 2016, the Obama White House issued a call to action urging state lawmakers to adopt the California model and get rid of noncompetes. Lobel, the University of San Diego law professor, said that Friday’s approach of calling on the FTC to create a federal rule is a stronger step, and one that she believes falls within the FTC’s powers.

“It’s squarely within the charge of the FTC to regulate unfair practices,” Lobel said, and that includes the labor market. “Wage fixing is just as unfair as price fixing — all of those are unlawful, and we should tackle them.”

The order could also mark a significant change for tech given the industry’s notoriously low rates of labor organization.

“A unionized worker has economic leverage with their employer through their collective action,” said Heidi Shierholz, senior economist and director of policy at the Economic Policy Institute. “But a non-unionized worker, essentially the only power — the only economic leverage — they have with respect to their employer is the fact that they could quit and go somewhere else.”

But, Shierholz added, “the devil’s in the details.” If the FTC doesn’t make noncompete agreements illegal but instead just makes them unenforceable, she said, companies could keep getting employees to sign them, and applying pressure that way — as 19% of California workers know all too well.

“There’s lots of good research showing that that — even just signing it, even if it’s not enforceable — has a real effect.”