Without these ads, there wouldn’t be money in fake news

A short video explaining where the money behind fake news organizations comes from.

It’s never been easier to launch a wildly profitable online media empire. Whether you’re an aspiring mommy blogger or political pundit, $10 gets you a URL and online storage. Fill out a short form and copy-paste some code to get ads on your website.

Lure in some readers and you’ll have no trouble making money.

Every 1,000 visitors earns you at least a dollar or two with traditional banner ads sold through Google — boxes typically pitching products that readers have browsed online. But the same readership generates three times the income through recommended content ads. Usually displayed in a familiar grid, they couple crazy headlines with scintillating pictures — a must-click combination dubbed chum.

“Site Reveals an Alarming Amount About Your Past (Photos & More).”

“Atrial Fibrillation Foods You Must Avoid!”

“19 Bikinis That Aren’t Covering Anything.”

It’s that mix of ads that significantly funds much of the Internet, including major media websites LATimes.com, Bloomberg.com and Newsweek.com.

But the advertising technology companies that offer these easy-to-use services impose few regulations, inspiring sites that publish fake news to maximize revenue.

They take advantage of a general rule in online publishing: the crazier the story, the greater the interest. Capitalizing off this year’s presidential election, they post exaggerated political news articles — some with made-up quotes and details — that millions of consumers can’t resist opening.

Al Sharpton ditching the U.S. because of Donald Trump? President Obama banning the national anthem at sporting events? Anything to get more attention on Facebook — and more income through recommended content ads.

Thwarting fake news is now a major focus of the tech industry. Facebook, where the stories spread, has pledged to combat misleading publishers.

But it’s the ad networks that can do more to stop fake news. They hold the power to remove the financial incentive for trafficking in deception.

The rise of chum

Years ago, the only way for a publisher to sell an ad was to work directly with an advertiser. Google, AOL and others realized that this was expensive and cumbersome for both sides and built huge businesses simplifying the process through software. With just a few clicks, advertisers now automatically place messages across many publications at once. Hundreds more tech firms including Content.ad in Irvine and AdSupply in Culver City followed suit.

Israel-founded companies Taboola and Outbrain brought the lucrative recommended content ads to the forefront about a decade ago, hoping to assist publishers in two ways. Publishers can buy chum on other sites, luring readers to help fulfill viewership promises made to their own top advertisers. And publishers can get a revenue boost by housing a grid of chum links on their own stories.

It has been an effective combination for reputable sites and misleading ones.

Businesses will spend more than $30 billion on non-video online ads in the U.S. alone this year. Advertisers pay dimes or pennies each time their message gets clicked. The tech companies in the middle split the proceeds with websites that run the ads. Publishers tend to get a bigger portion the larger and more prominent they are, sometimes higher than 50%. Entrepreneurs in the misleading news business have said the pennies add up to tens of thousands of dollars in monthly income.

To advance their businesses and promote an open market, most ad technology providers set a low bar for joining, meaning that even the crummiest content can be a pathway to income. And by taking advantage of Facebook and Google, where users may click on links without considering their validity or source, millions of readers can be wrangled by a small operation creating a few stories a day.

Many ad tech firms vet sites for child porn, hate speech, violent content or illegal drugs. But checking for accuracy of information hasn’t been a consideration, which is why a Conservative101.com article with a headline claiming that Sharpton was leaving the U.S. continues to absorb ad money.

A fake story and its funders

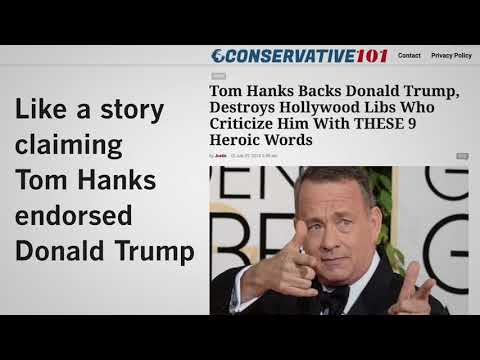

In the weeks before last month’s presidential election, more than 100,000 Facebook users promoted articles that claimed or implied that Hollywood star Tom Hanks had endorsed Trump for president.

Misleading articles stated that Hanks — who supported Hillary Clinton — had pledged to vote for Trump, a man the actor described to the BBC in October as a “self-involved gas bag.” Hanks’ publicist declined to comment for this story.

Conservative101.com, ReaganCoalition.com, WorldPoliticus.com and a several other websites that published Hanks-Trump stories produce mostly legitimate stories. But they generate inconsistent viewership, relying on the viral posts for the bulk of their traffic, according to an analysis by research firm SimilarWeb. As much as 90% of the hundreds of thousands of monthly visitors to their publications arrive by clicking on a Facebook link, SimilarWeb data show.

The six websites with Hanks-Trump stories use more than a dozen advertising software providers including Revcontent, Google and Teads, according to tech analysis firm BuiltWith. Others suppliers are Adblade, Amazon.com Associates, Criteo and Spoutable.

Some ad companies didn’t respond to requests for comment. Nearly all the rest said they’re wary of judging fact and fiction.

AdSupply Chief Executive Justin Bunnell questioned whether stating that Hanks endorsed Trump represents an accidental inaccuracy or intentional deceit. Being the arbiter in that case is not a position he finds comfortable or financially sound.

“It’s not practical to have an elaborate vetting process,” Bunnell said. “I’m not giving out security clearances here.”

He’s also unsure about the trade-offs. Does monetizing fake news harm America’s free market and democratic values more than banning such a business?

“I like to do things for the net good of society, but the deeper I look into this, it’s a more thorny situation,” Bunnell said.

Content.ad Chief Revenue Officer Michael Rosenberg said the 45-employee Irvine company isn’t an industry leader so it’s monitoring what bigger players do before setting policy.

Pressure for change

Advertisers and more highly trafficked publishers are increasingly urging ad networks to clean up their acts. Media critics and politicians want action too. They fear that misinformation leaves readers ill-equipped to make decisions. Violent consequences were highlighted last week when a man allegedly brought a rifle to a Washington, D.C., pizzeria that fake news websites had pegged as a haven for pedophiles.

How deceiving a website must be to rise to the level of offensive remains a matter of debate.

“There may be little consensus on which sites and pages are fake news, but frankly those same concerns were raised about hate and even pornography,” said Benjamin Edelman, a Harvard University associate business professor who studies Internet operations. Sanctioning them “is doable and probably not that hard given the concentration of fake news on a modest number of sites.”

Some are making adjustments. The top two online advertising companies, Google and Facebook, have banned fake news sites from using their ad services. DoubleVerify, which provides a tool for advertisers to restrict where ads run, released a new filter for fake news websites.

ShareThrough is keeping tabs on its customer list for websites that cross a line. Revcontent is expanding beyond a ban. As early as next year, it wants to provides ratings of advertised links describing a website’s quality and political slant. Data analysis and reader feedback would fuel the measurements.

“Providing more information is how you empower people,” said Revcontent CEO John Lemp, who vowed to donate any profit tied to fabricated news.

It’s unlikely that any action by ad technology suppliers or social media services would fully thwart purveyors of deliberately fake news. Advertising industry executives say there will always be bottom-feeders who will supply websites trafficking in pirated content, illicit drugs and worse.

There’s also the element of human nature. Advertisers want eyeballs and people are more likely to click on racier content. Though established news organizations may filter out the tawdriest ads, other sites will run them and profit from them.

“Lots of junk is there because that’s what people call on,” said Mike Rosenberg, chief revenue officer at Content.ad.

By running the same types of ads as large media companies, misleading online publishers have given themselves a familiar look that readers may struggle to differentiate from traditional news sources. Until major publishers drop such ads in favor of new business models or focus more heavily on direct sales, the fake news ecosystem and the confusion between fact and fiction is left to endure.

Inside the ad tech industry, the ongoing focus on changing the shape, fonts and sizes of ads to garner more clicks suggests that chum is still evolving, not vanishing.

Its continued existence also shows that it works. Ad tech firms have little reason to change a product that customers are buying.

Chum brings in the viewers that advertisers covet, sometimes without revealing where they came from. In many cases the transactions run through an opaque system that leaves advertisers unaware of the sites on which their ads appeared.

Soylent, Lowermybills.com, Wisebread, Nucific and other Southern California companies whose ads came up alongside Hanks-Trump stories didn’t comment on their involvement. Others said they plan to seek increased transparency and more assurances about where their ads get placed.

“Fake news sites probably perform as well as a real news website, so I don’t think it makes an impact on my bottom line,” said lifestyle blogger Andrew Wise, who paid for a link to his LifeTailored.com website on AmericanReviewer.com’s Hanks-backs-Trump story. “That being said, from an ethical perspective, I would prefer to work with a business that prohibits fake news.”

Twitter: @peard33

ALSO

State Farm’s request to block $100 million in refunds to be considered next week

Trump picks Southern California fast-food executive Andy Puzder for Labor secretary

Donald Trump keeps financial ties to NBC reality show ‘Celebrity Apprentice’