Photoshop is hard to learn. Adobe thinks artificial intelligence can help

A teary-eyed Mala Sharma felt vindicated as she stood outside a school for impoverished children in India. A student had snatched the Adobe Systems executive’s iPad and had a go with the company’s simplest video editing program. He nailed it, creating a quick video that Sharma said amused his teacher and peers.

For years, Adobe has been the dominant provider of expensive editing tools to professional content producers. But the recent experience in India with her company’s newer, consumer-oriented app showed Sharma firsthand the value of expanding efforts to make tools approachable to anyone.

“I stood there with tears in my eyes because I felt like in that minute Adobe touched and changed that child’s life,” Sharma said. “That’s the ultimate vision: to make that possible for everyone.”

Free mobile apps and a shift to online offerings have led to significant inroads. But the San Jose company’s newest initiative is a steep investment in artificially intelligent services. Adobe envisions what it calls Sensei as an automated virtual assistant that for now reduces rote handiwork in certain tasks, but eventually would help first-time users make the most of its apps or guide them when they’re stuck.

See the most-read stories in Business this hour »

What Google search does for finding websites or Amazon.com’s Alexa for shopping, Adobe wants Sensei to do for making films, editing photos and designing products. Sensei features spread across Adobe’s software suite, including marketing databases and PDF readers.

Adobe expects big interest in Sensei, pointing to popular creative apps as a sign of demand. For instance, Instagram has amassed 600 million users by giving beginning photographers simple ways to give their work a professional look.

“We used to serve the Adobe magic to the highest end of users, but in the mobile-first era, average consumers want that magic,” Adobe Chief Technology Officer Abhay Parasnis said. “The heart of Sensei is, ‘Can we make our tools and workflow much more broadly accessible?’”

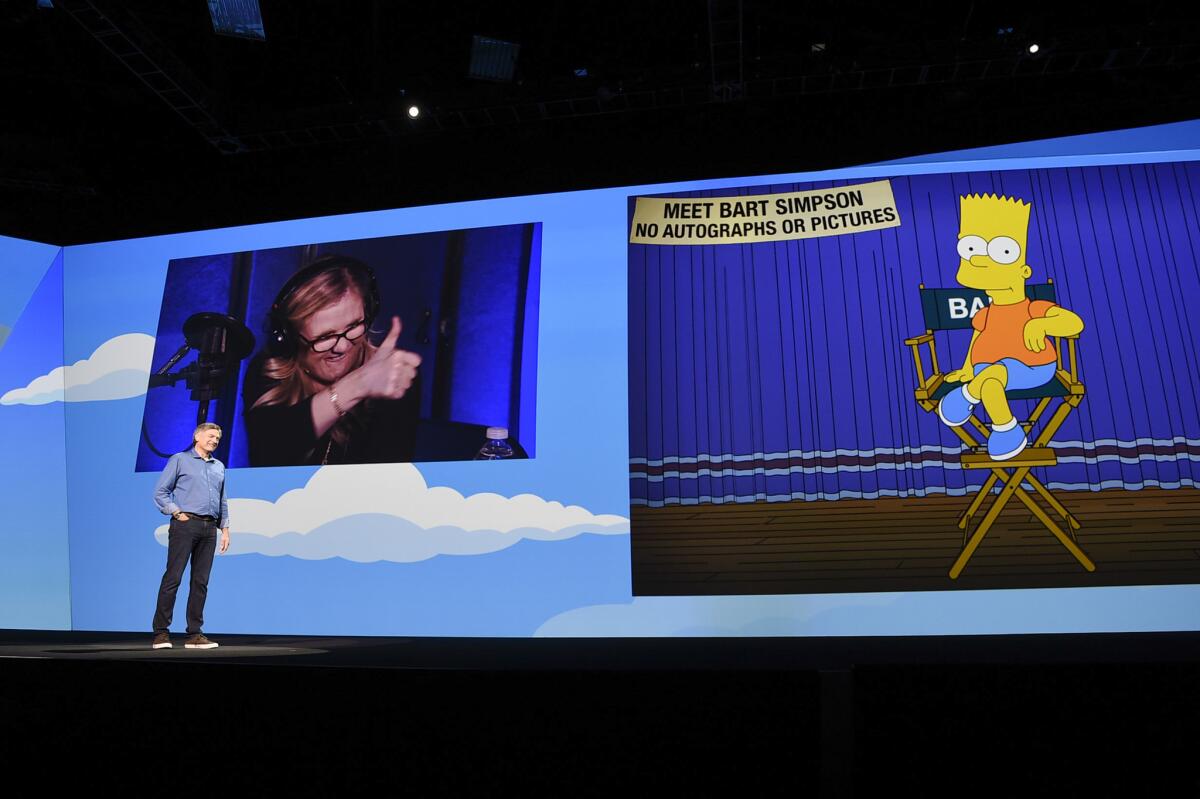

At an unveiling spectacle held for thousands of graphic designers, video editors and other users at the San Diego Convention Center this fall, Adobe showed how Sensei could point users to licensable images that resemble ones they like but don’t have permission to use. It can do the same with fonts, analyzing handwriting to recommend a look-alike typeface.

During editing, Sensei can identify lips and eyes in a photo and allow users to change facial expressions — for instance, widening a grin — without overly distorting the rest of a face. Offering “The Simpsons” star Bart as an example, Adobe also showed how Sensei can automatically manipulate a cartoon character’s mouth so that it moves in sync with a voice actor’s speech.

Sharma imagines Sensei as an instructor too, accepting commands by voice, text or click. Unsure how to make a tweak in a photo? Sensei could anticipate your desire and make suggestions. And they could be personalized, borrowing from decisions made at similar junctures by people a user follows on Adobe’s social networking service Behance.

“The user doesn’t have to do the hunting and pecking and the looking,” Sharma said. “As we understand what they are trying to do and we understand what is the kind of work that inspires them, we can give them intelligent solutions in real time.”

Getting Sensei right is crucial to Adobe’s growth, financial analysts say. Whether you’ve mastered it or have never tried it, Photoshop software is so widely recognized that you’ve probably uttered something like “I’ll just Photoshop it later.”

But increasingly sophisticated, cheaply available editing apps on smartphones could eventually relegate Photoshop and other Adobe programs to being complicated luxuries. There’s no doubt that they are powerful technology. But it can take hours of classes to know how to use the programs well.

Sensei is meant to knock out hurdles. Chief Executive Shantanu Narayen said Adobe shareholders are excited about the untapped opportunity, which could lift the company’s nearly $6 billion in annual sales by as much as $3 billion over the next few years. Investors are pleased with initial efforts. A growing percentage of Adobe software subscribers are first-time users. About 35 million have logged onto mobile apps such as the free Adobe Spark Video program that the student in India picked up.

“People who have a story to tell find Adobe is the gold standard and they keep coming,” Narayen said in an interview. “They want instant gratification and ease of use. If we allow them, they will come.”

Adobe shares have quadrupled to over $100 in the five years since the company began pushing online subscriptions instead of one-time purchases of its software.

Adobe executives aren’t overly worried about the rising competition.

“There’s people who want to communicate in the moment [and] take a photo … on Snapchat,” Sharma said. “We see our mission foremost in … going beyond the moment.”

The separation exists because Snapchat, Instagram, VSCO, Google Photos and tools from Facebook and Apple prioritize simplicity over sophistication (dozens of features instead of thousands). But artificial intelligence could boost the rival offerings over time, increasing the pressure on Adobe to outdo them.

Adobe’s advantage is that its virtual monopoly among professionals gives the company unrivaled data, enabling it provide unique insights to users, said Rodney Nelson, equity analyst at Morningstar. Some Sensei features including the similar image finder will be available to other companies to use and build upon in their own apps, widening the possibilities.

Adobe has long relied on the smarts of computers for features like one that quickly removes unwanted objects in a photo. But branding such options as Sensei is meant to signal Adobe’s dramatically larger focus in artificial intelligence over the next decade, Parasnis said. Every product and engineering employee will be trained on how Sensei technologies work.

Sensei leverages machine-learning breakthroughs in recent years. Computers have gone from humans heavily training them to recognize obvious images of cats to understanding even partial images of cats on their own.

With the understanding of curvature and textures, Sensei can automatically adjust the shadows in an image to reflect the lighting in the backdrop. Future manifestations of Sensei would allow for automatically inserting and rearranging objects while maintaining a natural look. In the voice and video sphere, an experimental tool synthesizes any speaker’s voice, which provides for indistinguishable (but artificial) edits to an earlier recording.

“To Adobe’s credit, they already had this technology lurking and they’ve made it more prominent,” Abhinav Kapur, an analyst at BTIG, said of the Sensei branding. “It’s absolutely crucial. Any big software company going forward needs to have data-crunching components in the product suite.”

Sensei features might not be the reason that someone pays $10 a month or more for access to Adobe software. But they could amount to something that gets people to keep paying. People could misuse the new tools, but Adobe doesn’t want to hold people back from sharing their stories.

“We see this lowering user friction and ‘democratizing’ the creative process,” Piper Jaffray analyst Alex Zukin wrote of Sensei.

Now the question is whether Sensei on top of existing initiatives will be enough to preserve Photoshop as a verb, and Adobe’s general dominance, for years to come.

Twitter: @peard33

ALSO

Qualcomm is fined $865 million by South Korean antitrust regulator

Amazon says its Echo devices were hot sellers during its ‘best ever’ holiday season

Snapchat maker Snap gets foothold in Israel with acquisition of Cimagine

This $1,499 gadget hopes to do for tea what Keurig did for coffee