Jovani Ramirez wakes well before dawn most work days to head from his Santa Clarita home to his 6 a.m. shift as a cook at the Beverly Hilton hotel, one of the three jobs he juggles to support his family.

When he’s done at 2 p.m., Ramirez travels to the nearby Century Plaza Hotel for another eight-hour stint. Then some nights he picks up a few Uber driving gigs. Ramirez said his commute can stretch to three hours each way, and he averages about 3½ hours of sleep a night.

For the record:

8:25 p.m. July 3, 2023An earlier version of this story said 62 contracts for workers represented by Unite Here Local 11 at Southern California hotels were set to expire June 30 at midnight. Sixty-one contracts expired.

8:26 a.m. June 9, 2023An earlier version of this article said hospitality workers in Los Angeles and Long Beach earn an average hourly wage of $39.31. That hourly rate is what is needed to afford an average two-bedroom apartment in L.A. and Long Beach, a union says.

“It’s kind of hard for me because I never see my kids,” ages 16, 12, 10 and 7, Ramirez said.

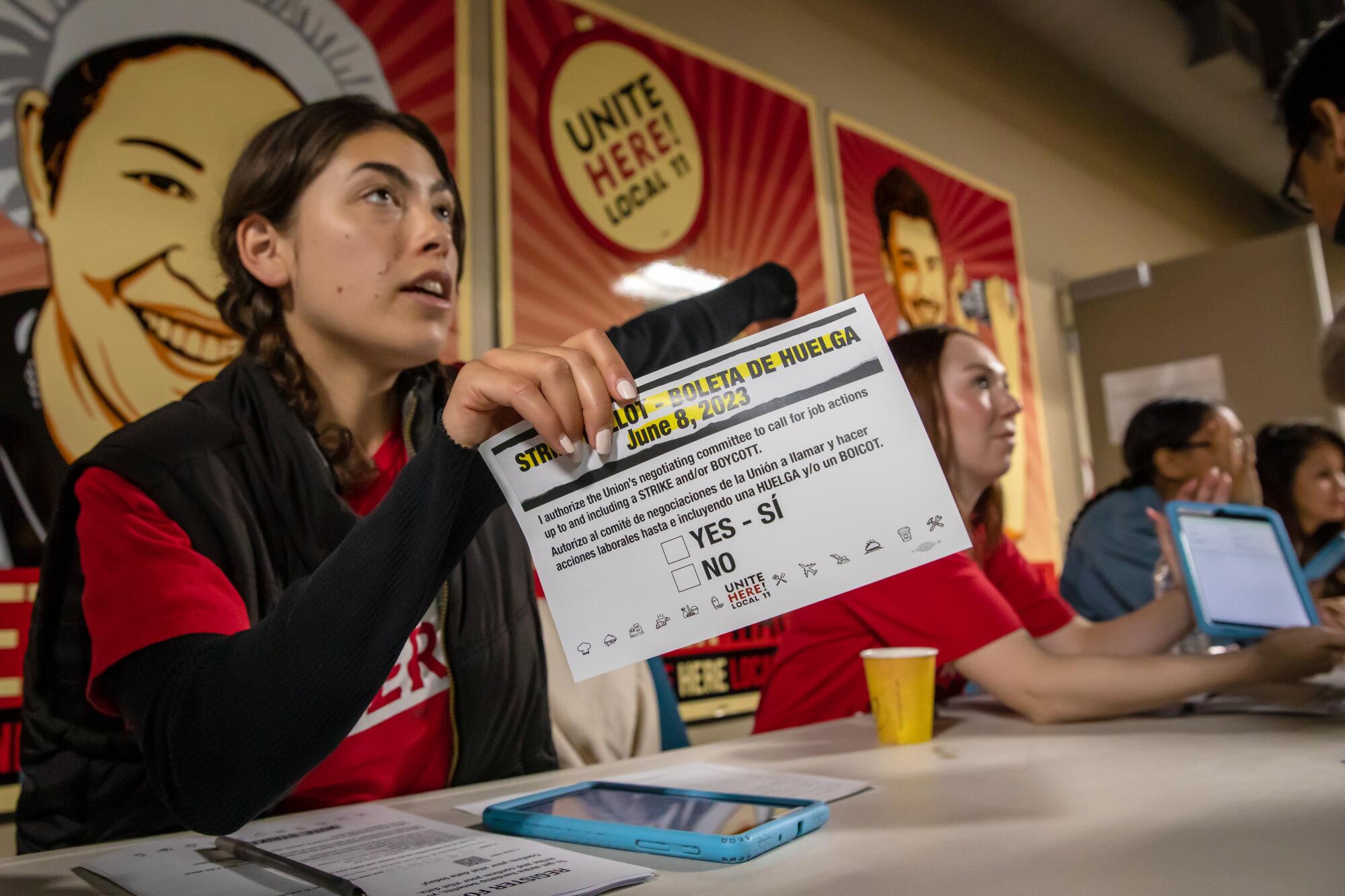

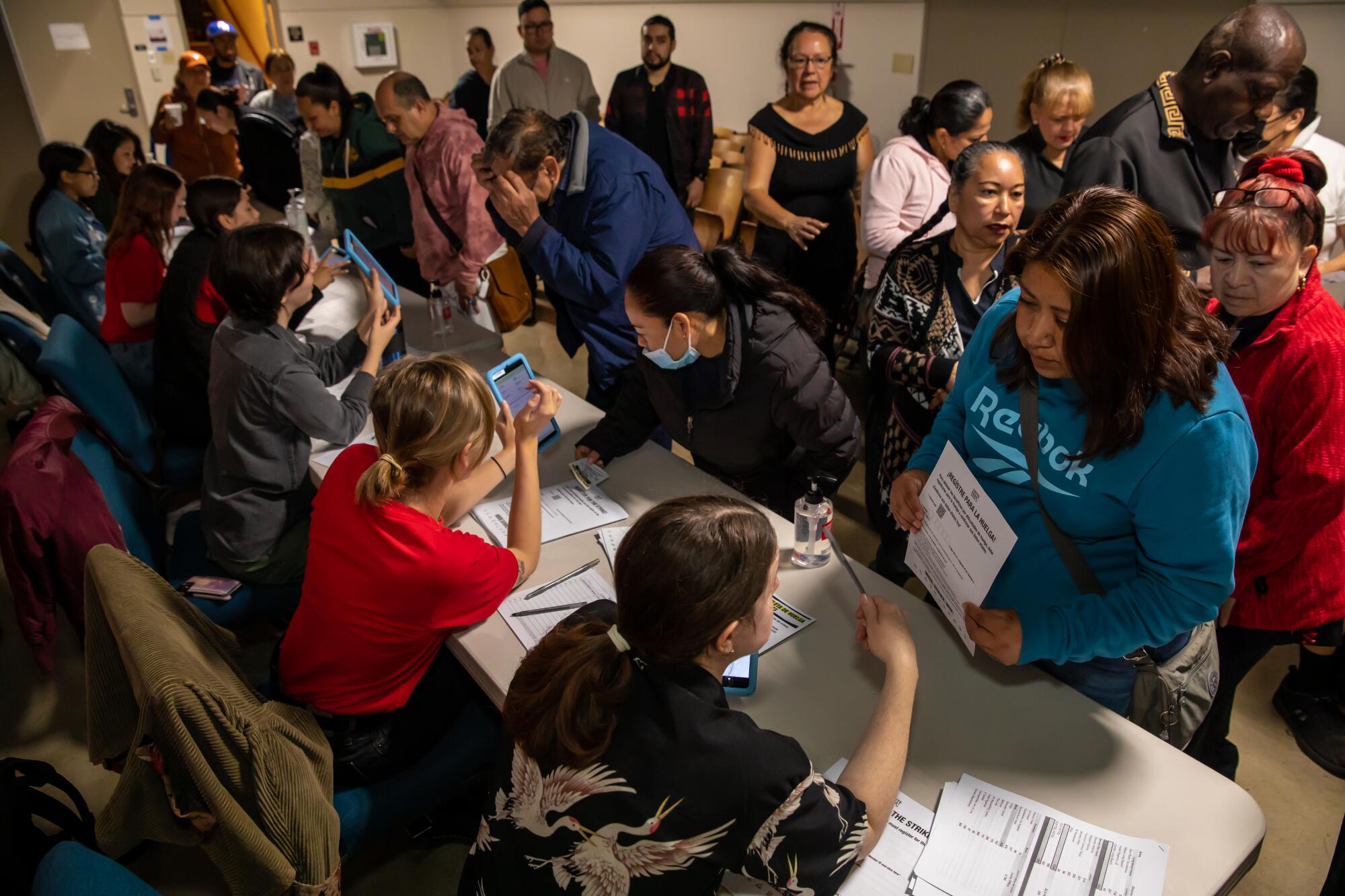

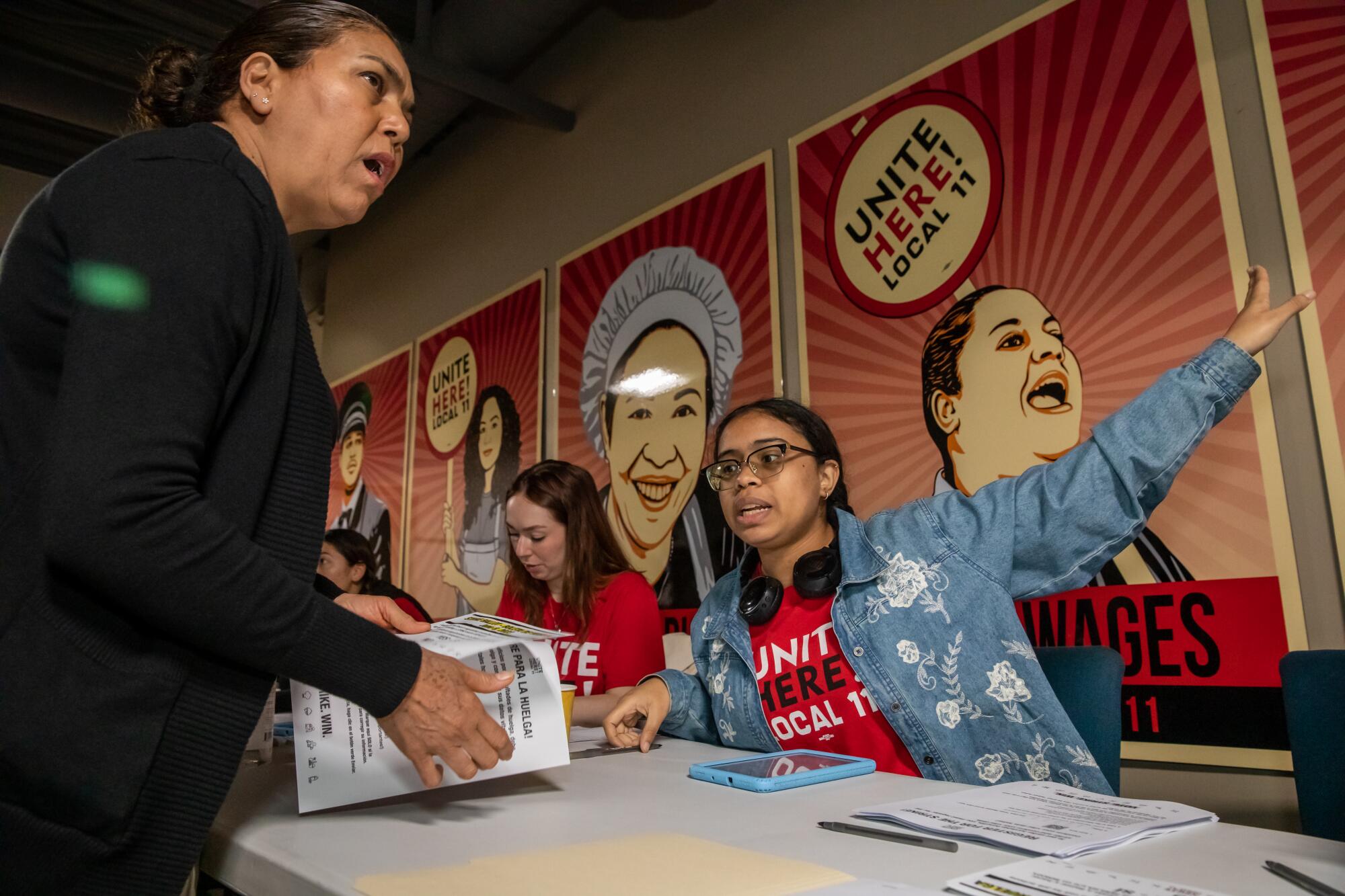

Ramirez on Thursday was among Southern California hotel workers who voted overwhelmingly to authorize their leaders to call a strike if their employers don’t agree to major wage boosts in contract negotiations covering 15,000 workers in Los Angeles and Orange counties.

The authorization was approved by 96% of those who voted, Unite Here Local 11 said Thursday night. If a contract agreement isn’t reached, a strike could begin as early as the Fourth of July weekend and would be the largest in modern U.S. history, the union said.

The previous record holder happened in 2018 when nearly 8,000 housekeepers, bartenders and other workers walked off the job at 23 Marriott hotels in eight U.S. cities, including San Diego, San Francisco, Oakland and San Jose. That strike lasted more than two months before final contract agreements were reached.

“I think we have to put a little bit in our power so we can get stronger and begin getting what we asked for. We ask what we ask for because that’s what we deserve,” Ramirez said.

Unite Here Local 11 says bargaining for higher pay so that workers can afford housing is crucial as L.A. gears up to host the World Cup and the Olympics.

When asked what a new contract with higher pay would mean for him, Ramirez began to cry.

“My youngest son has Down syndrome. I want to spend more time with my family. I want to not have to work two jobs,” he said. Ramirez said his wife works part time because their son requires special schooling that isn’t available near where they live.

Union officials have said their demands are crucial protection to ensure more workers aren’t priced out of their neighborhoods and all are fairly compensated as Los Angeles gears up to host the World Cup in 2026 and the Summer Olympics in 2028.

After a month of negotiations, hotels have failed to make any wage proposal, and the union called a strike authorization vote to “send a message to the industry that we’re very serious,” said Kurt Petersen, co-president of Unite Here Local 11, which represents more than 32,000 hospitality workers across Southern California and Arizona. Its members are non-management hotel employees, including people who staff front desks, clean rooms and work in hotel restaurants.

Contracts are expiring June 30 at 61 Southern California hotel sites, including luxury stays such as the Westin Bonaventure in downtown Los Angeles, the Fairmont Miramar in Santa Monica and the Beverly Wilshire in Beverly Hills.

“We’re 22 days from the expiration of the contract and there’s not a single nickel that they have offered as a raise for anyone in any of these hotels,” Petersen said. “It’s a total disrespect for their workers who sacrificed extraordinarily during this pandemic.”

Marriott International, Hyatt and Hilton Hotels & Resorts are among the major employers in talks, and they didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Peter Hillan, a spokesperson for the Hotel Assn. of Los Angeles, an industry group, said a Fourth of July weekend strike would “hold the community hostage” and hurt the hotel workers by harming the city’s tourism appeal while the industry is getting back on its feet after pandemic shutdowns.

He said homelessness and the housing crisis have already given Los Angeles “a black eye” and have deterred tourism, particularly hotels’ business from conferences and conventions.

“It’s self-serving and injurious to the L.A. community to consider a strike at this time,” Hillan said.

He declined to weigh in on negotiations between hotel companies and the union. The association’s position, he said, is that displacement of workers due to high rental housing costs is not the responsibility of hotel companies and rather is an issue for city leaders “to engage in and solve universally.”

“This is not specific to hotel workers. Teachers, construction workers, this happens to them also,” Hillan said. “We work as hard as we can to pay good wages and benefits.”

A Hyatt executive said last week that the company was disappointed the union was pushing a strike authorization so soon in negotiations.

The hotel giant “is committed to bargaining in good faith,” Michael D’Angelo, a Hyatt vice president of labor relations, said in a statement issued May 31, noting that Hyatt and Unite Here have successfully negotiated agreements this year in other markets, including Long Beach. “We remain optimistic that a mutually beneficial agreement can be reached without a strike.”

The union is asking for a $5 immediate hourly wage increase, and a $3 boost each subsequent year of the three-year contract, for a total of $11. The union has also made proposals related to healthcare, pensions, workload and a policy against hotels using E-Verify, a federal system used to check work eligibility, to protect immigrant workers.

Fast-food workers make up 11% of all homeless workers in California and 9% in Los Angeles County, according to a report released Tuesday by Economic Roundtable.

Hourly pay ranges from $20 to $25 for housekeepers and $22 to $28 for dishwashers and cooks, the union said.

Los Angeles City Councilmembers Curren Price and Katy Yaroslavsky in April proposed increasing the minimum wages of workers at larger hotels and Los Angeles International Airport to $30 an hour by 2028. The city’s chief legislative analyst was directed to report back on the economic impact of the proposal, which a coalition that includes the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce said would cost the region revenue and jobs and would cause prices to rise at local hotels as operators pass costs along to consumers.

The union said that on average, a local hotel housekeeper would need to work 17 hours a day to afford housing. Hospitality workers would need to earn $39.31 an hour to be able to pay rent on an average two-bedroom apartment in Los Angeles and Long Beach, the union said.

Many of the hotel workers interviewed Thursday said they have left Los Angeles to reduce costs and find affordable housing, but the moves have added to their commutes and gas expenses.

With her 7-year-old daughter in tow, Jaavonda Dartis waited to cast her vote outside a Beverly Hilton ballroom that the union rented as a polling place, one of many spots around the region where workers could vote.

Dartis said she is living paycheck to paycheck, even though she lives in a low-income building where rent is $1,080 per month. To pay for extracurricular activities for her daughter, who attends school in Inglewood, she sometimes pays other bills late.

When Dartis first started working at the Beverly Hilton in 2019, she said, the towers were under renovation. But business has returned and is better than before the pandemic, she said.

“They’re booked solid until next year. Yet they can’t give us these raises? This is ridiculous,” said Dartis, a phone operator at the hotel, site of the annual Golden Globe Awards.

COVID-precautionary lockdowns helped to inflate hospitality workers’ wages because scarce workers could command higher pay. But workers interviewed said high housing costs and gas prices in Southern California strain their budgets to the breaking point.

Every morning, housekeeper Francisa Gutierrez drives up to an hour and a half from San Bernardino to the InterContinental Los Angeles in downtown L.A.

“The babysitter makes half of what I make in wages,” Gutierrez said through an interpreter. She earns $22 an hour and spends at least $200 on gas and $1,800 on rent, she said.

Gutierrez said she rarely sees her children, ages 2 and 6, because of work.

Gary Safady’s plan for a luxury hotel has lined up A-list names as backers. It also has plenty of high-profile celebrities among its critics.

Ruth Hernandez, a housekeeper at the Hotel Figueroa, arrived at Unite Here Local 11’s downtown office to vote from Koreatown. Although she is able to live near her job, she said, she hopes a new contract would help secure wages high enough that her co-workers wouldn’t need to live so far away.

“There’s a big workload and it’s easy to get injured. We need a better raise to be fairly compensated and have a comfortable life,” Hernandez said through an interpreter.

Southern California tourism has rebounded sharply from pandemic levels, with Los Angeles last year seeing 46.2 million visitors (91% of the visitor count in 2019, the last full pre-pandemic year), who spent $21.9 billion (89% of the pre-pandemic level), according to the Los Angeles Tourism and Convention Board. Orange County also experienced significant growth.

Many hotels nationwide eliminated automatic daily room cleaning during the pandemic when workers were especially scarce. Unite Here’s Petersen said hotels haven’t reinstated daily room cleaning as a way to save money even though “their industry is booming ... which means our room attendants end up having to clean rooms that are dirtier because they haven’t been cleaned in several days, and there are fewer room attendants working.”

Workers interviewed said their hotels are understaffed and employees are overworked.

“It’s hard to keep employees. They expect so much from such little staff and the pay stays the same,” said South Los Angeles resident Edwin Salguero, who works the 11 p.m.-to-7 a.m. overnight shift at the InterContinental in downtown. He volunteered to work night shifts because of a promised $1 extra in hourly pay, he said, but that pay boost never materialized.

“They care less now. It’s the most brutal part of my work. We’re getting the job done but we’re not getting compensated [fairly],” said Salguero, who helps support his wife and three children.

Filadelfia Alcala, a housekeeper at the Waldorf Astoria in Beverly Hills, said wealthy guests who come in often spend lavishly. It’s a stark contrast to her own pay, she says.

Alcala eats at the hotel’s underground workers’ cafeteria with Santa Rodriguez, who says workers at the luxury apartments and hotels in the area are moving farther and farther away.

“It’s really about living a dignified life,” Rodriguez said through an interpreter, “and making sure that working-class people can afford to live where they work.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.