Despite doctors’ concerns, University of California renews ties with religious hospitals

)

As the University of California’s health system renews contracts with hundreds of outside hospitals and clinics — many with religious affiliations — some of its doctors and faculty want stronger language to ensure that physicians can perform the treatments they deem appropriate, including abortions for women or hysterectomies for transgender patients.

University of California Health is in the middle of a two-year process to renew contracts with affiliate hospitals and clinics that help the university deliver care in underserved parts of the state. Many of the agreements are with faith-based facilities, including prominent hospitals operated by Dignity Health, Providence, or Adventist Health. Such arrangements generate more than $20 million a year for the UC system and help the public university approach its goal of improving public health.

The current policy, adopted in 2021, states that UC physicians have the freedom to advise, refer, prescribe, or provide emergency care, covering cases in which moving a patient “would risk material deterioration to the patient’s condition.” But some UC doctors and faculty worry that physicians would be allowed to perform certain surgeries only in an emergency.

They want to add a clause stating that physicians have the right to perform procedures in a manner they deem advisable or necessary without waiting for the patient’s condition to get worse.

Others have gone so far as to urge the university to reject partnerships with hospitals that have ethical and religious directives against sterilization, abortion, some miscarriage management procedures, and some gender-affirming treatments. The Academic Senate, a faculty body that helps the university set academic policies, and other faculty councils urged the university’s president to avoid working with healthcare facilities because many have restrictions that “have the potential for discriminatory impact on patients.”

UC regents demanded that university personnel face no restrictions when practicing at Catholic hospitals. It hasn’t worked out that way.

In response, university leaders have pledged publicly to ensure that doctors and trainees can provide whatever care they deem necessary at affiliated facilities but haven’t made changes to the policy language.

“We’ve made it clear that the treating provider is the one to decide if an emergency exists and when to act,” said Dr. Carrie Byington, executive vice president for University of California Health, at a fall meeting of the UC Board of Regents, the governing board of the university system.

UC Health has given itself until the end of this year to make contracts conform to its new policy. During the October board meeting, staffers estimated that one-third of the contracts had been evaééluated. Administrators haven’t said whether the current policy thwarted any contracts.

In June 2021, the regents approved the policy governing how its doctors practice at outside hospitals and clinics with religious or ethical restrictions. Regent John Pérez made significant amendments to a staff proposal. At the time, it was celebrated as a win by those advocating for the university to push back on religious directives from affiliates.

But some doctors and faculty said Pérez’s proposal was then wordsmithed as it was converted from the regents’ vote into a formal policy months later. Some questioned whether the policy could be interpreted as restricting services unless there is an emergency, and that it does not go far enough to define an emergency.

“It passes the commonsense test, but in reality, this is just the federal minimum requirement of care,” Dr. Tabetha Harken, director of the Complex Family Planning, Obstetrics & Gynecology division at the UC-Irvine School of Medicine, testified before the board.

Pérez declined to comment to KHN.

At the regents’ meetings, concerned doctors offered examples of pregnancy and gender-affirming care they believe would be at risk in some hospitals. One was tubal ligation or sterilization procedures immediately after birth to prevent future pregnancies that may put the woman at risk. Another may mean that a trans male with a mental health referral for gender-affirming surgery may not get a hysterectomy at a religiously restricted hospital.

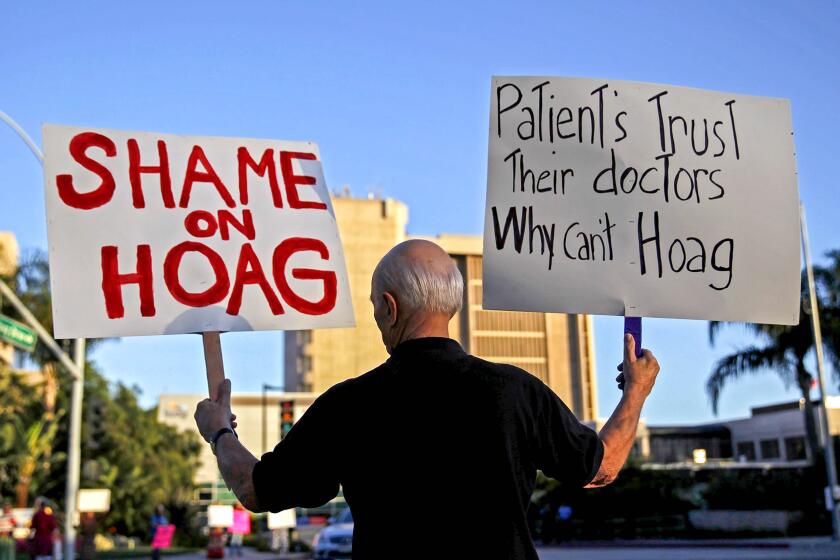

California’s Hoag Hospital wins its battle to shed itself of Catholic healthcare restrictions

But it’s unclear whether physicians are running into problems. UC Health leaders said there have been no formal complaints from university doctors or trainees practicing at affiliate medical centers about being blocked from providing care.

The debate stems from a partnership with Dignity Health, a Catholic-affiliated hospital system. In 2019, UCSF Medical Center leaders considered a controversial plan to create a formal affiliation with Dignity. Critics voiced opposition in heated public meetings, and the plan drew condemnation from dozens of reproductive justice advocates and the gay and transgender communities. UCSF ultimately backed off the plan.

When it became clear that UC medical centers across the state had similar affiliation contracts, faculty members raised additional concerns. Janet Napolitano, then president of the UC system, convened a working group to evaluate the consequences of ending all agreements with organizations that have religious restrictions. Ultimately, the group stressed the importance of maintaining partnerships to provide care to medically underserved populations.

Dignity Health has already reached a new contract that adopts the updated UC policy. Chad Burns, a spokesperson for Dignity, said the hospital system values working with UC Health for its expertise in specialties, such as pediatric trauma, cancer, HIV, and mental health. He added that the updated agreement reflects “the shared values of UC and Dignity Health.”

Some UC doctors point out that they have not only public support, but legal standing to perform a variety of reproductive and contraceptive treatments. After California voters passed Proposition 1, the state constitution was officially changed in December to affirm that people have a right to choose to have an abortion or use contraceptives.

Other doctors say the university system should prioritize public service. Dr. Tamera Hatfield, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at UC Irvine, testified at a regents’ meeting that she had never been asked to modify care for patients based on religious restrictions since her department formed an affiliation with Providence St. Joseph Hospital-Orange about a decade ago.

“Partnering with faith-based institutions dedicated to serving vulnerable populations affords opportunities to patients who are least able to navigate our complex health systems,” she said.

This story was produced by KHN (Kaiser Health News), a national newsroom that provides in-depth coverage of health issues and that is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KHN is the publisher of California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.