Column: Big business goes after another Biden appointee for doing his job, which is protecting consumers

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce really piled on the sinister adjectives when it announced its campaign against financial regulator Rohit Chopra two weeks ago.

In just the headline and the first two paragraphs of its announcement, the chamber described Chopra, director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, as “out-of-control,” “ideologically driven,” “radical,” “extreme” and “heavy-handed.”

Sounds pretty bad.

Repeat offenses...[are] par for the course for many dominant firms.

— CFPB Director Rohit Chopra

If you’re a banker, that is.

If you’re a consumer of financial services, however, you should interpret this broadside as the chamber expressing irritation at a government regulator who is doing the job he’s paid to do — in this case, protect consumers from abuses by the financial services industry.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It’s proper, indeed, to view the chamber’s attack on Chopra in the context of similar campaigns the business community has waged against appointees and nominees of President Biden who were intent on regulating the industries under their jurisdiction.

That includes the crass and hypocritical efforts last year to paint Saule Omarova, a banking law expert at Cornell Law School who had been nominated as comptroller of the currency, as a closet communist. Those efforts ultimately resulted in Omarova’s withdrawing her name from consideration for the post.

Banks and the right wing know Saule Omarova may be an effective regulator, so they’re absurdly attacking her as a communist.

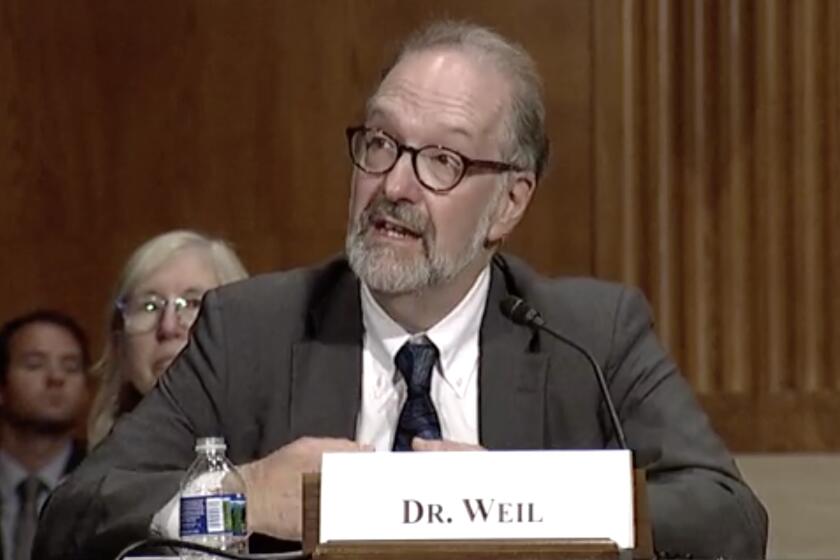

Also last year, the chamber and other industry lobbies attacked David Weil, a labor law expert at Brandeis and a former Labor Department official.

Weil’s putative offense was taking “positions on critical questions” such as “whether an employee would be exempt from overtime, finding joint employment relationships, and whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor.”

Never mind that these were issues that fell squarely within the bailiwick of the agency’s Wage and Hour Division, where Weil had served in the past and which he was nominated to head again. The chorus of industry disapproval grew so deafening that Weil withdrew his name earlier this year.

Then there’s the campaign waged by Amazon and Meta Platforms (the former Facebook) against Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan, aimed at forcing her to recuse herself from FTC proceedings against the companies, largely because she has developed expertise about how they conduct business. (She hasn’t done so.)

The business community’s objection to Chopra is grounded in the pro-consumer direction the agency has taken under his leadership after its supine groveling to business interests during the Trump administration. In 2017, it may be recalled, Trump installed his budget director, Mick Mulvaney, as the CFPB’s acting director.

Mulvaney boasted to a bankers convention that his appointment was “apparently keeping Elizabeth Warren up late at night, which doesn’t bother me at all.” The bankers laughed appreciatively. (Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts had been instrumental in creating the CFPB; Chopra, as it happens, launched his public career as a staffer in her office.)

Mulvaney promptly suspended a CFPB regulation designed to prevent payday lenders and other profiteers from abusing low-income customers who couldn’t repay the loans by running up fees on them, among other sleazy practices.

He abruptly withdrew a federal lawsuit against four allegedly abusive installment lenders. And he closed an investigation into World Acceptance Corp., a payday lender in his home state of South Carolina that had been accused of abusive practices but had contributed at least $4,500 to his congressional campaigns.

David Weil would have enforced federal labor law leading the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division, so Republicans killed his nomination.

Kathy Kraninger, Mulvaney’s successor, continued his effort to disembowel the agency. She sometimes approved settlements with investigatory targets that required them to pay nothing in compensation to consumers.

Chopra isn’t cut from that cloth. As CFPB chair, he has taken aim at credit card late fees and bank overdraft fees, which he quite rightly calls “junk fees” through which “large financial institutions feast on their customers,” leaving them feeling “gouged,” as he said in a January news conference announcing an inquiry into these charges.

(As Helaine Olen of the Washington Post observed, after Chopra fired his shot across the banks’ bows by noting that they were collecting $15 billion a year in overdraft charges, several moved to pare back their fees.)

Chopra has also launched an investigation into “buy now, pay later” credit firms, which he suggested may be misleading consumers about their debt and obligations. “Buy now, pay later is the new version of the old layaway plan,” he said in December, “but with modern, faster twists where the consumer gets the product immediately but gets the debt immediately too.”

He has also launched an inquiry into payment platforms operated by Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Square and PayPal, seeking to determine whether they might be used to conduct “invasive financial surveillance and ... use this data to deepen behavioral advertising, engage in price discrimination, or sell to third parties.”

These initiatives are likely to make financial services firms’ skin crawl. So it’s unsurprising that the chamber has launched its campaign in conjunction with the American Bankers Assn., the Consumer Bankers Assn. and the Independent Community Bankers of America.

Reading the chamber’s bill of particulars against Chopra, it’s hard to avoid the impression that, as Hamlet’s Queen Gertrude might say, the body doth protest too much.

For example, the chamber expresses indignation at Chopra’s observation (in a lecture this March at the University of Pennsylvania) that “repeat offenses ... [are] par for the course for many dominant firms.” He mentioned specifically big banks, Big Tech and Big Pharma.

Facing a tough regulator for the first time, Facebook and Amazon are trying to sideline FTC Chair Lina Khan.

The chamber calls this view “extreme and inaccurate.”

Is that so? Let’s see.

Start with banks. Since 2000, JPMorgan Chase, the nation’s largest commercial bank, has been slapped with more than $30 billion in penalties by state, federal and industry regulators in nearly 200 cases, according to the violation tracker maintained by Good Jobs First.

The total includes a $920-million assessment imposed by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in 2020 for an eight-year scheme to manipulate the precious metals and U.S. Treasury markets that the CFTC commissioner called “unparalleled” in its scope.

That was at least the third market manipulation accusation JPMorgan had faced in recent years, including a bid-rigging scheme in the California electricity market in 2010 and 2011 for which the bank paid a $410-million penalty.

Then there’s Wells Fargo, which has made its name almost synonymous with consumer abuse.

In 2015, when JPMorgan, Barclays, Citigroup, Royal Bank of Scotland and UBS all pleaded guilty to federal felony charges related to foreign exchange market manipulation, Securities and Exchange Commission member Kara M. Stein objected to the SEC’s granting them a waiver from serious penalties because of what she termed “the recidivism of these institutions.”

Altogether, the five banks had received 23 waivers of penalties for wrongful conduct over the previous nine years.

Big Tech? In 2019, the Federal Trade Commission fined Facebook $5 billion for violating the terms of a settlement over privacy practices that it had reached with the same agency in 2011.

Big Pharma? Johnson & Johnson, Merck and Pfizer, three of the largest drug companies in the world, have all paid multibillion-dollar settlements to resolve allegations of wrongdoing or in personal injury lawsuits.

In 2009, Pfizer paid penalties totaling $2.3 billion, including a $1.195-billion fine, which federal prosecutors called “the largest criminal fine ever imposed in the United States for any matter,” and pleaded guilty to a federal charge; it was the company’s fourth such settlement over the previous decade for illegally promoting its drugs.

These are all manifestly “dominant firms.” Under the circumstances, Chopra’s observation about corporate recidivism wasn’t “extreme and inaccurate,” but charitable.

“I am the acting director of the CFPB,” Mick Mulvaney told a group of bankers Tuesday, “something that’s apparently keeping Elizabeth Warren up late at night, which doesn’t bother me at all.”

For all that, it’s really not Chopra’s observation, accurate as it was, that has gotten under the chamber’s skin. It’s the prospect of more expansive regulatory actions.

In a June 28 letter, the chamber upbraided Chopra for instructing agency examiners to keep an eye out for “discriminatory” conduct and linking that to the agency’s statutory authority to regulate “unfair, deceptive, and abusive acts or practices.”

The chamber’s position is that “discrimination” and “unfairness” are two different things and the law gives the CFPB authority only over the latter.

That’s a curious position, given that “discrimination” surely falls into the category of unfair things, but also because the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which created the CFPB, specifically says that the bureau has the authority to protect consumers from “unfair, deceptive or abusive acts and from discrimination.”

The chamber surely knows this because it quotes that exact language in its letter, placing the “and” in italics for emphasis. Anyway, it’s not our place to question the chamber’s decision to have its lawyers torture legislative diction in a seven-page, single-spaced letter to Chopra.

It is our place, however, to ask who the audience is supposed to be for the chamber’s campaign against Chopra, which includes a “six-figure digital ad campaign.”

The digital ad in question is a nearly two-minute video praising American financial companies for having worked with the CFPB “to try to ensure fair regulations were enacted,” and grousing that Chopra is “breaking time-tested norms of policymaking.” Chopra, the ad says, “has an outsized and distorted view of his role and power.”

Translating this corporate-speak into English is easy. The chamber’s complaint is that the warm relationship businesses had with Chopra’s Trumpian predecessors has been sundered. The “time-tested norms of policymaking” it cherishes were those that fashioned policies to the banks’ advantage.

But those weren’t the norms envisioned by Warren or by the CFPB’s first director, Democrat Richard Cordray, a serious regulator whom the chamber and other business lobbies also hated.

The Chamber of Commerce is playing a long game here. It knows it has no prayer of dislodging Chopra as long as a Democrat holds the White House. But if the administration and Congress swing to the Republicans, the CFPB will have a big bull’s-eye painted on its back. In that case, consumers should be ready to hold on to their wallets.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.