‘Unified and militant’: Grocery workers get double-digit pay raises in new contract

Whipsawed by the pandemic, spurred by fury over wage stagnation and alarmed by inflation, Southern California’s unionized grocery workers gained their biggest pay raises in decades Thursday as they ratified a new contract with the region’s largest food chains.

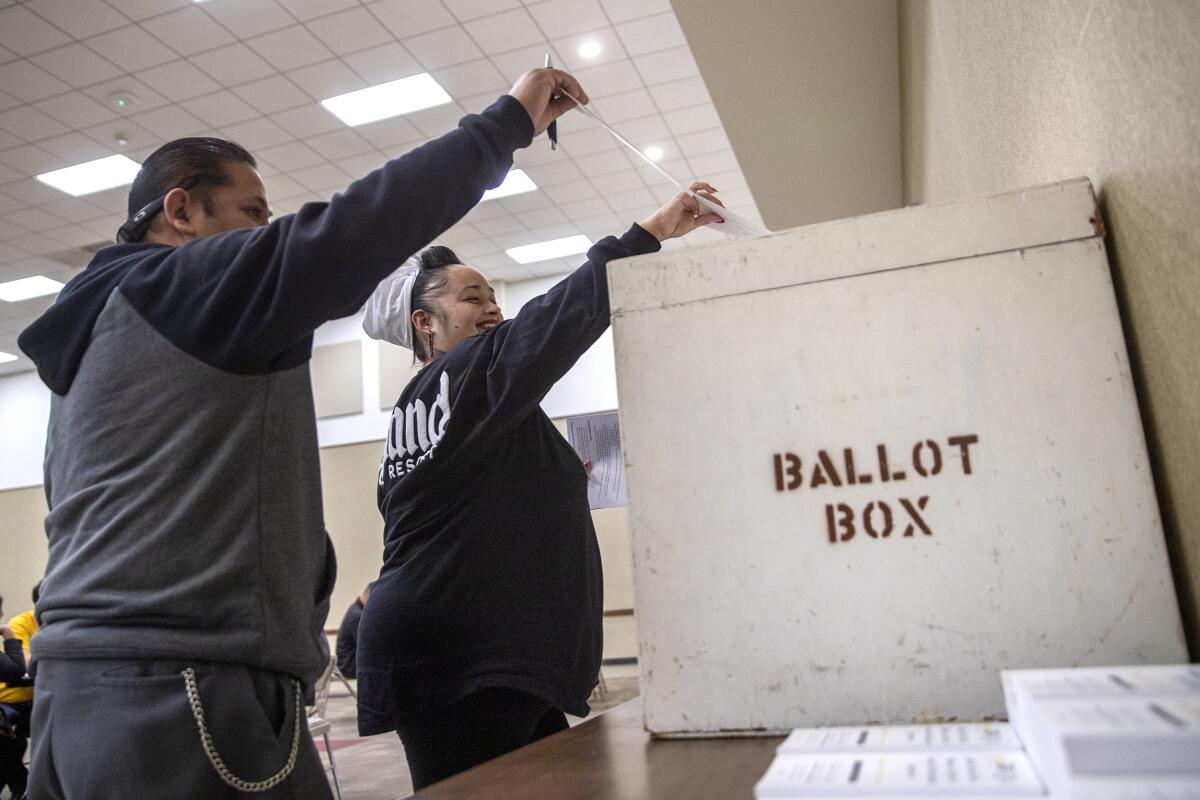

The three-year contract’s overwhelming approval, by 87%, followed strike authorization votes two weeks earlier by union locals representing 47,000 employees at 540 Ralphs, Albertsons, Vons and Pavilions stores from San Diego to San Luis Obispo.

After four months of bargaining, Kroger, the parent company of Ralphs, and Albertsons, which owns Pavilions and Vons, agreed to raises of 19% to 31% over current pay levels for most workers. Part-time employees, about 70% of the workforce, are guaranteed 28 hours weekly, up from 24.

“The companies were afraid of a strike,” said Kathy Finn, secretary-treasurer of United Food and Commercial Workers Local 770 in Los Angeles. “Our members were more unified and militant than they’ve been in a long time.”

Ralphs said the company was “pleased” with the agreement and Albertsons called it “fair and equitable.” Neither company elaborated on the reasons behind the large pay boost, more than 2½ times what the chains originally proposed.

Across California and the nation, a pandemic-driven labor shortage has made it harder to retain and hire staff. Workers are quitting for higher-paying jobs and older employees, fearing infection, are retiring in droves.

“This is the best contract for the employees in 20 years, but also for the companies,” said Burt Flickinger, managing director of Strategic Resource Group, a top retail consulting firm. “We have the most acute worker shortage since World War II. Higher wages and benefits are an investment in worker loyalty and productivity.”

In 25 years, union membership in Southern California’s grocery industry has dropped from 90% to about 35% as nonunion big-box stores expanded into food, he said. The new UFCW contract will help counter nonunion competition, Flickinger said.

In their own words, former Tesla employees describe what they call a racist work environment that led California to file a civil rights lawsuit against the company.

“Walmart and Target are running out of stocks in key categories because they don’t have enough workers at stores or warehouses. With the high cost of living in Southern California, this contract could bring back experienced workers to union stores — people who retired early because of COVID and now can’t pay their bills.”

In January, the companies had proposed a raise of just $1.80 an hour over three years for the highest-paid long-term employees including cashiers. They ended up agreeing to $4.25, raising those wages to $26.75.

Another group, including lower-paid deli workers and shelf stockers, will get a $5.25 boost over three years, raising their wages to $22.27. Workers will progress to top wage tiers at a faster rate and medical benefits will expand.

The bottom third of the workforce, baggers and clerk’s helpers, will get a 95-cent raise to $16.34 an hour.

The wage hikes for top-paid workers also apply to Food 4 Less, a Kroger-owned chain with 6,200 workers, whose contract last year was tied to expected raises at Ralphs.

Earlier this month, UFCW workers at Stater Bros., a chain with 15,000 Southern California employees, also gained hefty increases of $4.50 over three years for top-line cashiers, clerks and meat cutters, along with a 28-hour minimum guarantee for most part-timers.

“Grocery workers and their union scored a big win,” said Occidental College politics professor Peter Dreier, co-author of a recent report by the nonprofit Economic Roundtable on Kroger. Polls showed the public was sympathetic to essential workers who suffered hardships during the pandemic, and the companies would have lost a lot of business in the event of a strike, he said.

The Economic Roundtable report documented a sharp drop in real wages for Southern California Kroger workers since 1990, when the highest-paid food clerks earned $13.65 an hour, the equivalent of $28.32 today. That 22% decline in pay worsened as the company switched more workers to part time “so few of even the best-paid front-line employees make middle-class incomes,” the report said.

Jay D Willey, 42, began as a minimum wage bagger at age 18 and worked his way up to meat manager, a unionized position, at an Anaheim Hills Vons. The father of two was counting on the $5 raise over three years that union negotiators first proposed.

“Even if we had gotten $5 upfront that wouldn’t catch us up to the curve of inflation over the last 20 years,” he said. His current wage of $24.78 an hour, along with his wife’s pay as a clerical worker, isn’t enough for the family to move out of their two-bedroom apartment and buy a home, he said.

Now, he fears, “inflation is going to keep going,” one reason he voted against ratifying the contract.

If low wages and inflation worries fueled grocery workers’ militancy, the pandemic turbocharged their anger. They were considered “essential” and hailed as “heroes,” but complained that the companies failed to offer timely protective equipment and allowed hazard pay to expire after two months.

Among the 20,000 grocery workers represented by UFCW Local 770 in Los Angeles, Ventura, Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties, 7,730 were reported to have caught the coronavirus, according to data provided to the union by the companies.

At Local 324, based in Orange County, 3,670 grocery employees out of 14,000 got sick. And at Local 1167, which represents workers mainly in Riverside, San Bernardino and Imperial counties, 5,770 out of 17,000 members fell ill.

“After this pandemic, we had a chance to stand up and say to the companies, ‘You guys owe us big and we’re trying to collect now,’” Willey said.

Ashley Manning, a 32-year-old flower manager at a Ralphs in San Pedro, caught COVID. Her daughter, mother and grandmother got sick too. “We put our lives on the line for this company to earn billions in profits,” said Manning, who voted for the contract. “We deserved more.”

The single mother was living paycheck to paycheck on $18 an hour. Then she lost three months of work during the pandemic and had to move out of an apartment she could no longer afford. “The company didn’t have plexiglass up at the time and they weren’t giving us protective equipment,” she said.

Manning’s 9-year-old was out of school and she had no child care. But her bosses, she said, were pressuring her to work 48 hours a week, rather than her regular 40. Her 79-year-old grandmother volunteered to help, but then passed away from the virus after three weeks in the hospital.

Manning applauded provisions in the new contract to prevent forced overtime and establish health and safety committees in every store.

And with the extra $5.25 per hour over three years, she said, she will be able to pay bills, afford higher gas prices and send her daughter to the YMCA for after-school care.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.