Column: The Biden economy is booming. Why aren’t Americans happier with it?

U.S. unemployment is at its lowest since the pandemic hit, wages are on an upswing, 6.1 million jobs have been created since last December and economic growth is expected to reach nearly 6% this year, after inflation.

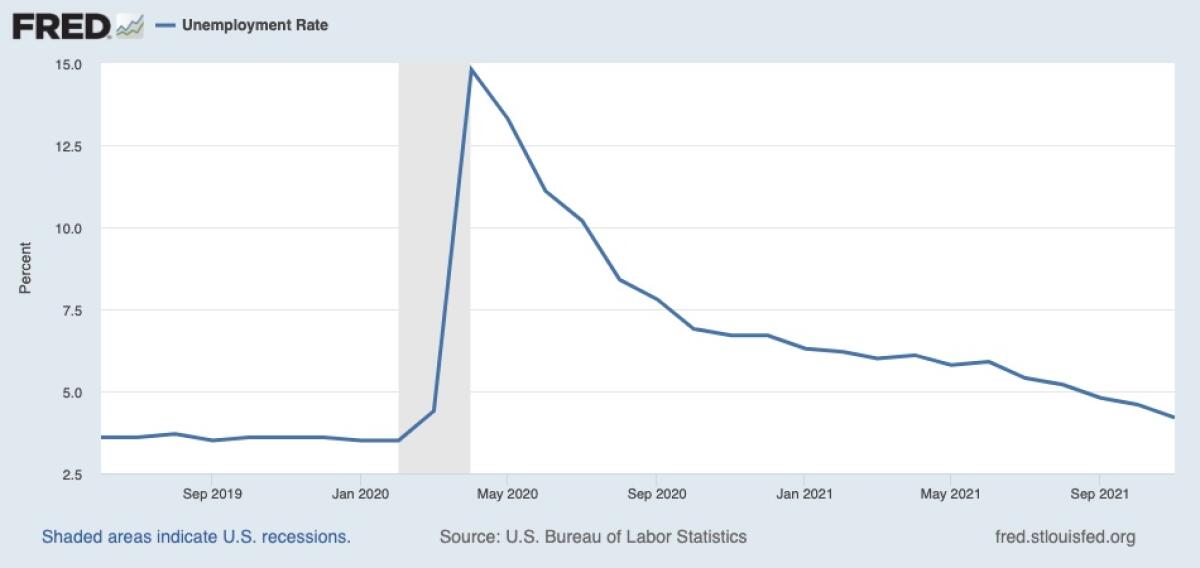

Each of those statistics are stunningly good news. The unemployment rate of 4.2% in November is a sharp reduction from the peak 14.8% rate reached in April 2020, as the pandemic began to bite.

Average weekly earnings growth of 4.9% in November over a year earlier is among the strongest trends in wages this century. And the growth in gross domestic product handily outpaces the rate of any year since 2000 and certainly the average of 2000-2019, which was 2.08%.

The pandemic continues to play a pretty significant role in what we’re seeing as the ebbs and flows of the labor market in general, but we’ve added over 6 million jobs this year.

— Elise Gould, Economic Policy Institute

What’s not to like?

Plenty, it would seem. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index has plummeted by 12.8% this month compared to a year ago. Washington political pundits are already writing off President Biden’s chances of reelection in 2024, and are even more caustic about the Democrats’ chances of holding on to majorities in the House and Senate in November’s midterm elections.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In the public’s mind, what should be viewed as a “Biden boom” has run into two headwinds.

“I don’t think the public will really accept the good news about the economy until they feel more confident about the pandemic,” says Robert J. Shapiro, a former economic advisor to the Clinton and Obama administrations who now runs his own consulting firm, Sonecon. “That’s one thing. The second thing is that there is a competing story, and that’s inflation.”

Shapiro notes that even though the data showing a recovery are much stronger than the statistics on inflation — in that the recovery has been proceeding since as long ago as the end of 2020 and inflation has become an issue only in the last few months — inflation has been most strongly felt in two areas where people tend to make weekly purchases, gasoline and food.

Given the implications of economic conditions on political outcomes, it’s worth examining what’s really happening in the U.S. economy and what goes into peoples’ assessments of how they’re doing.

The latest inflation numbers shocked even pessimistic economists, but they’re still transitory.

There’s no question that the economy is recovering from the damage the pandemic caused in 2020. It’s fashionable, and not entirely inaccurate, to point out that governments — especially presidents — have less power to influence economic growth than is generally assumed.

In this case, however, a tide of fiscal stimulus has saved the economy from a more severe slump than it might otherwise have incurred from the pandemic, and powered forward through 2021.

The stimulus includes a series of recovery and rescue packages including checks to households and augmented unemployment benefits that began in 2020 and continued into this year.

Biden’s American Rescue Plan, enacted in March, encompassed several assistance provisions aimed at middle- and working-class households, including a child tax credit that aims to deliver up to $3,600 per child to families into next year.

Monthly payments to households covering half the benefit end this month unless Congress acts to extend the program, with the balance to be paid after families file their tax returns for 2021 next year.

The nature of the recovery, however, confuses even those with their fingers closest to the pulse of consumers.

In a recent interview with the Associated Press, for example, Bank of America Chief Executive Brian Moynihan asserted that consumers have been “spending money at a faster rate than I have ever seen,” based on evidence from the bank’s debit and credit cards. He added: “Now they are worried that these costs are going to go up faster than their wages.” That was conjecture, based on consumer sentiment statistics that haven’t been reflected in spending patterns.

There’s also the tendency of the press, exemplified by the Washington press corps, to view the economy through a political prism — that is, how will conditions affect partisan fortunes — without examining too closely the multitudinous undercurrents swirling beneath the surface of the gross numbers.

Are inflation fears unreasonable? It depends on how you’re spending your money.

They’re also inclined to assume that conditions today will be the same as conditions tomorrow, except more so: In other words, if inflation is running at an annual rate of 6.8% now, that’s the figure that voters will have in mind in November 2022 and 2024, unless it’s even higher.

Let’s start with consumer behavior. As Moynihan attested, sales are on fire. Consumers spent $639.8 billion at restaurants and retail stores in November, according to Commerce Department figures released Wednesday. That’s an increase of 18.2% over November 2020, well beyond the 6.8% inflation rate over the same period.

Several factors contribute to the spending surge. One is the recovery in jobs.

“There’s reason to feel confident that we’re on track” for pre-pandemic labor market health by the end of next year, Elise Gould, senior economist at the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute, told me. “The pandemic continues to play a pretty significant role in what we’re seeing as the ebbs and flows of the labor market in general, but we’ve added over 6 million jobs this year, a recovery that’s much faster than we saw from the Great Recession.”

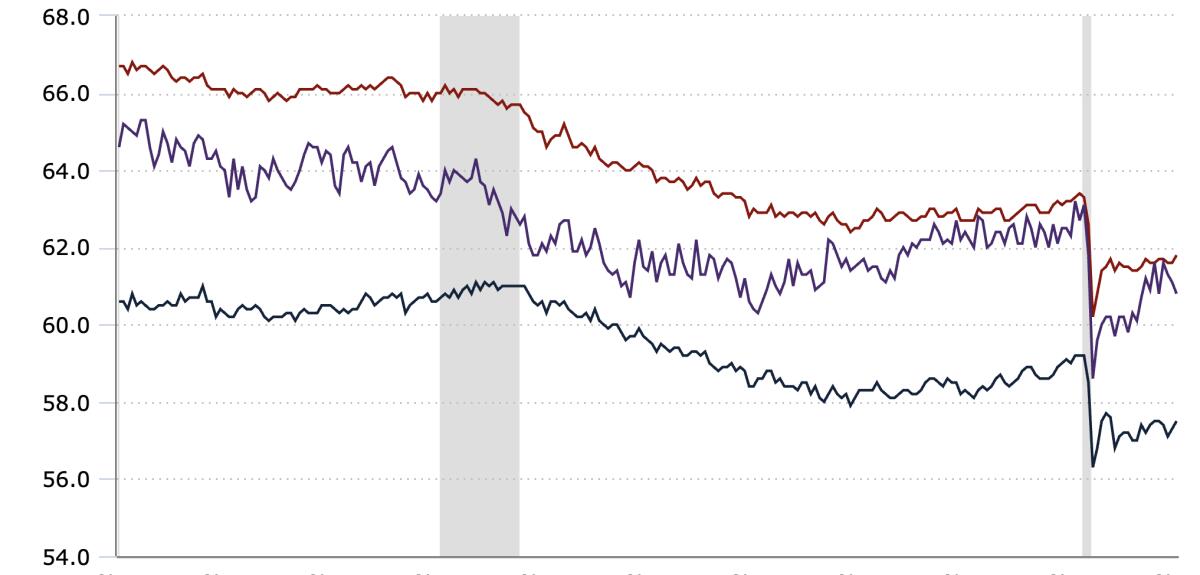

Not all jobs statistics are flashing bright green, but some are natural laggards. One is the labor participation rate, defined as the share of the working-age population that is employed or actively job hunting.

The rate had edged up to 63.4% in January 2020 after falling to a post-recession low of 62.4% in September 2015, then was forced down to 60.2% in April 2020 by pandemic shutdowns. In November, the rate came in at 61.8% — still well below the pre-pandemic figure, but rising.

The rate does illustrate the disparities of employment in America — the participation rate of Black workers and women fell further during the pandemic shutdowns and have recovered more slowly than that of white males.

Wages have been rising almost across the board, government figures show. It’s true that for many workers the most recent wage gains have been eroded by inflation, but that’s not the case for everyone.

Leisure and hospitality employees (the restaurant and hotel workers who were among the signature victims of pandemic closures) have enjoyed wage increases better than the annual rate of inflation since June — 12.3% in November compared to a year earlier, while inflation rose at an annualized rate of 6.8%.

That’s an indication of the unusual leverage that workers in those sectors have been enjoying because of their scarcity — employers have been forced to raise pay to lure back workers after the pandemic underscored the essential lousiness of front-line food and hotel jobs in America.

Pandemic concerns may have much to do with Americans’ reluctance to embrace good news about the recovery — especially with the prospect of new shutdowns to deal with the Omicron variant. But it seems plain that inflation is today’s governing economic narrative.

We’ve written recently that the current spike in prices has been misinterpreted — it’s not chiefly the product of economic overheating driven by the money supply. Rather, as Gould observes, “the inflation we’re seeing is being driven primarily by bottlenecks in the supply chain, not wages inflating out of control.”

Essentially, consumers’ eagerness to spend on goods has outstripped the pace of manufacturing and the capacity of seaports to accommodate shipments. Ports, however, have been working down their backlogs, and industrial production has been rising — up 5.2% in October over a year earlier, according to the Federal Reserve, including a 2.6% increase in consumer goods.

The anti-deficit crowd is wrong about deficit spending. Don’t let them kill the Build Back Better plan.

Gasoline prices are likely to come down, following the trajectory of crude oil prices. Government analysts expect spot prices for Brent crude oil, the international benchmark, to fall to $71-$73 per barrel by early 2022, from $84 in October. The government expects gasoline prices to fall by 15% next year from an average $3.39 per gallon in November.

That suggests that the Federal Reserve needs to move carefully in its efforts to combat inflation. The Fed opened the door Wednesday to as many as three boosts in interest rates next year, a signal that it’s prepared to tap on the monetary brakes to cool the economy.

But those steps could stifle job growth, particularly at the lower-wage end of the employment landscape, just as the job market returns to pre-pandemic health.

“It’s the wrong decision to slow the economy down,” Gould says. “Slowing it down prematurely will potentially hurt millions of workers who haven’t been able to get back into the market.”

The issue for the next few months may be more political than economic. “Biden has to get his arms around inflation,” Shapiro says. “But there’s not much the president can do about inflation. We don’t have many tools for inflation outside of slowing the economy.” That harbors its own pitfalls, however.

Will the public eventually come around on the economy? It may take time, for people’s perceptions of economic conditions tend to lag changes in those conditions, sometimes by many months. As long as the inflation rate remains eye-opening and the pandemic lurks on the horizon, what Shapiro describes — accurately — as “historic gains in jobs and incomes and real growth” will be overlooked.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.