Column: A new research paper adds to the evidence that COVID-19 came from animals, not a Chinese lab

A new peer-reviewed research paper points to the likelihood that the COVID-19 pandemic originated at a seafood and wildlife market in Wuhan, China, rather than from a Chinese laboratory studying bat viruses.

The paper, by University of Arizona evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey, supports the consensus among virology experts that the pandemic’s origin was natural — that the SARS-CoV-2 virus causing COVID-19 spread via contacts between humans and animals, first from bats, then to intermediate mammalian species, and then to humans. Worobey’s report was published Thursday in the journal Science.

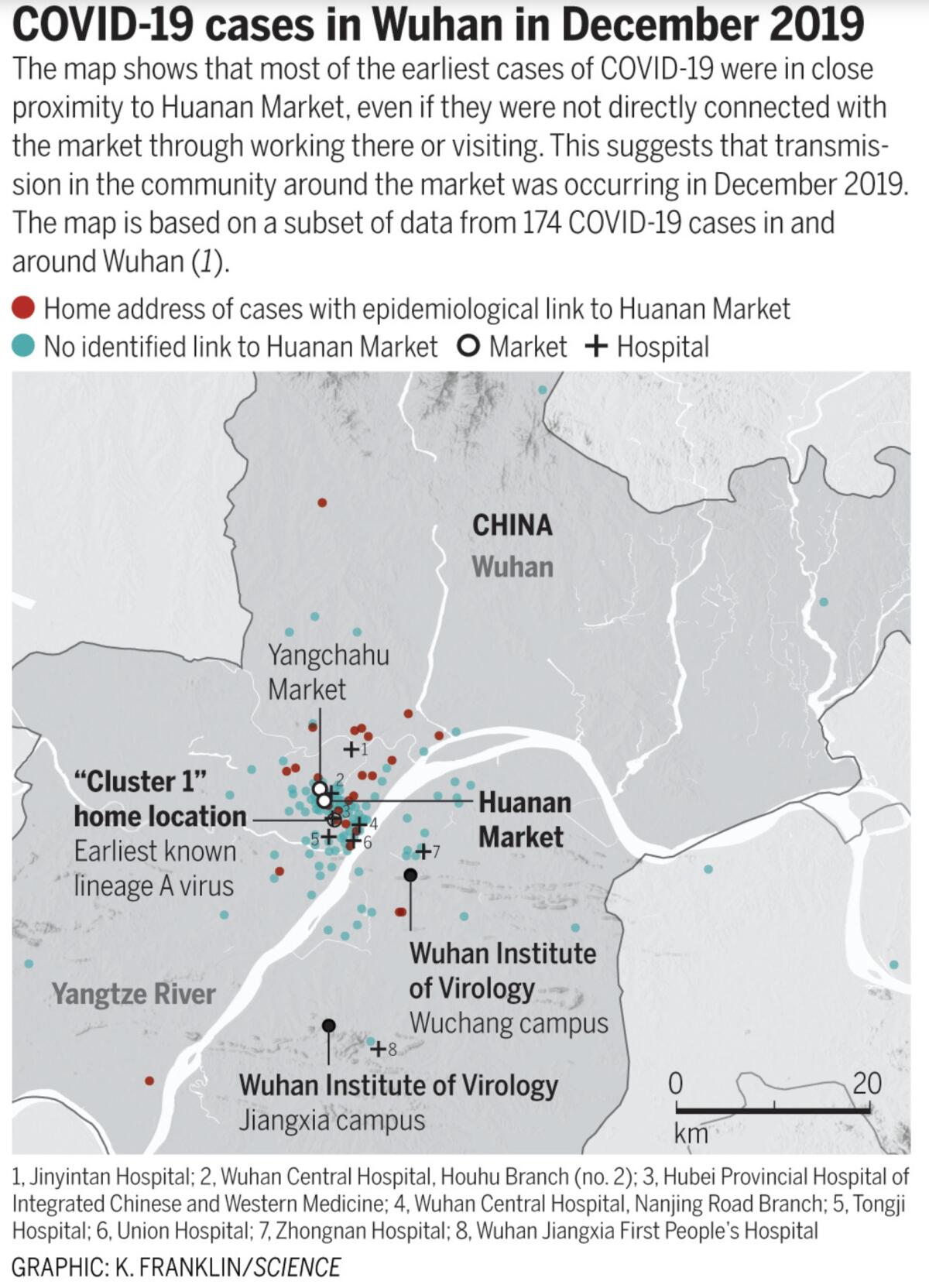

Worobey’s finding that the earliest identified COVID-19 cases centered around the Huanan Market in central Wuhan, the teeming metropolis where the outbreak apparently originated, “takes the lab-leak idea almost completely off the table,” he told me.

I would be very happy to have rejected the natural origin idea with this deep dive that I’ve done. But that’s just not how it worked out.

— Michael Worobey, University of Arizona

Worobey notes that more than half of the earliest identified COVID-19 cases were centered around the market.

The patients either worked at the market or had friends or other contacts who did, some of whom has visited their homes. Others lived in the “direct vicinity” of the market and may have been connected by only one or two transmissions of the highly infectious virus to someone with direct contact with the market.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“So many of the early cases were tied to this one Home Depot-sized building in a city of 11 million people, when there are thousands of other places where it would be more likely for early cases to be linked to if the virus had not started there,” he says.

For even early cases not directly linked to the market to arise among patients with home addresses clustered around the market “is an absolutely crucial point,” he says. “There’s no way you should expect a bunch of people with the earliest cases of the virus to live around the market unless it started at the market.”

Worobey’s paper takes aim at one of the central contentions of lab-leak proponents — that Chinese investigators tied the earliest COVID cases to the Huanan Market deliberately to steer attention away from government laboratories in Wuhan, specifically the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The institute was known to have been studying bat viruses purportedly similar to SARS-CoV-2.

In ‘Viral: The Search for the Origin of COVID-19,’ Alina Chan and Matt Ridley ignore scientific consensus in favor of specious, dangerous guesswork.

The paper undermines a competing theory that the SARS-CoV-2 virus leaked from the Wuhan institute or another lab studying bat viruses, whether inadvertently or as the result of secret bioweapon research. No evidence of research at those labs on viruses that could be precursors to SARS-CoV-2 has ever emerged.

The lab-leak theory originated in 2020 among ideologues in the State Department under then-President Trump. For them, blaming a pandemic on the Chinese government served the dual purposes of scoring points against a geopolitical adversary and distracting attention from the Trump administration’s incompetent response to the pandemic.

Worobey performed what he calls a “deep dive” into the chronology and pattern by which the earliest patients were identified at local and regional hospitals.

He found that doctors were finding patients with what turned out to be telltale signs of COVID-19, such as distinctive X-ray images of infected lungs and patients’ failure to respond to customary antiviral treatments, well before anyone identified the market as an epicenter of the infection.

That ruled out any chance that investigators had “cherry picked” the early cases to place blame on the market and divert it from government labs.

“The experiences of these hospitals as they went from not understanding anything about these new cases to its dawning on people at different places and different times that it’s spreading,” Worobey says, “that rules out ascertainment bias. The link to the market is real, not a mirage.”

Worobey concludes that the earliest known COVID-19 case was that of a female seafood vendor at the market, who fell ill on Dec. 11, 2019, and who told investigators that she knew of several other people who fell ill with the same symptoms around the same time.

That conflicts with the long-held identification of the first case as that of a 41-year-old male accountant who had been reported as falling ill on Dec. 8, despite living some 20 miles from the seafood market and having no connection to it.

Column: A declassified government report offers no support for the lab-leak theory of COVID’s origin

For months, adherents of the theory that COVID-19 originated in a Chinese government laboratory have hoped that an assessment President Biden ordered from the nation’s intelligence agencies would validate their suspicions. Their hopes are now dashed.

Worobey unearthed reports, confirmed by hospital records, that the accountant’s initial disease was related to a dental problem, not the virus. He did not fall ill with COVID-19 until Dec. 16, possibly during a hospital visit for his dental treatment or during a subway commute, and was hospitalized on Dec. 22.

Worobey’s paper adds to the growing body of research pointing to a natural, or “zoonotic” origin of the pandemic. That conclusion is regarded as overwhelmingly likely by virologists, especially since it matches the path by which viral pandemics have typically started throughout history.

Worobey was an instigator an co-author of a May 14, 2021, open letter published in Science and signed by himself and 17 other scientists urging a “dispassionate, science-based” inquiry into the two hypotheses.

He says he was concerned that the potential that the virus escaped from a lab had been dismissed “prematurely,” though “even at that time, I thought a natural origin was more likely, though I thought the lab-leak scenario was much more of a contender than I think now.”

Why do news outlets keep pushing the lab-leak theory of COVID’s origin?

Multiple research findings since the letter’s publication have dealt “body blows” to the lab-leak idea, he told me. Those include a published paper documenting that wildlife susceptible to the virus were being sold illegally at the Huanan Market, which Chinese authorities initially denied.

Other research has established that viruses collected from bats at a copper mine in Mojiang, on the Laotian border about 800 miles from Wuhan, and studied at the Wuhan institute are not nearly as genetically similar to SARS-CoV-2 as initially reported. That means they could not have been progenitors of the pandemic virus.

“I’ve been very much open to the lab-leak idea,” Worobey says. “I would be very happy to have rejected the natural origin idea with this deep dive that I’ve done. But that’s just not how it worked out.”

Proponents of the lab-leak hypothesis argue that no empirical evidence exists for a natural spillover, as no animals of potentially intermediate species have yet been found to carry antibodies for the virus.

That’s misleading, however. Scientists have found evidence pointing to an evolutionary pathway leading to SARS-CoV-2 from closely related viruses found in Laos and Cambodia, about 1,000 miles from Wuhan.

“The common wisdom is that we don’t know very much about the emergence of SARS-CoV-2,” virologist Robert Garry of Tulane University told a colloquium sponsored by the Global Virus Network earlier this week. He observed that nine coronaviruses that share structural features with SARS-CoV-2 have been known to infect humans, including the original SARS virus that spread globally and killed more than 700 people in 2002-2004, and the MERS virus that spread primarily in the Middle East in 2012.

“Compared to these other viruses, we actually know more about the emergence SARS-CoV-2,” he said. “We know more about how it got into the human population, we know the proximal ancestor, we know there’s a bat, we know the particular kind of bat, we have a virus that’s extremely close to SARS-CoV-2 [a virus isolated from bats in Laos], and we know the place that the virus spilled over” from animals to people.

“We’ve made actually some great strides with determining the origin of SARS-CoV-2,” Garry said. “You have to believe in quite a few impossible things to believe that the virus leaked from a lab at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.